The Neoliberal Era Was Not Pro-Market Enough

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Airline Deregulation Act

12 min read

The article specifically mentions Carter signing this act as an example of pro-market reform. Understanding this landmark 1978 legislation—its origins, implementation, and effects on the airline industry—provides concrete context for what 'deregulation' actually looked like in practice during the neoliberal era.

-

Stagflation

15 min read

The article references 'economic crises resulting from faulty management of the monetary system' and crises of the mid-1970s that neoliberalism responded to. Stagflation—the combination of stagnant growth and high inflation that plagued the 1970s—was the specific crisis that discredited Keynesian economics and opened the door to monetarist and supply-side reforms.

-

European single market

19 min read

Krugman blames 'fragmentation across European markets' for Europe's productivity lag, and the article argues this suggests Europe needs more neoliberalism. The European single market—its history, scope, and remaining barriers—directly explains what 'fragmentation' means and why market integration remains incomplete despite decades of EU policy.

In response to my article arguing that neoliberalism worked, some have pointed out that growth was actually slower in the neoliberal era, compared to the 1950s and 1960s. This view has had support among some prominent left-wing economists. Writing in 2010, Paul Krugman argued that:

Basically, US postwar economic history falls into two parts: an era of high taxes on the rich and extensive regulation, during which living standards experienced extraordinary growth; and an era of low taxes on the rich and deregulation, during which living standards for most Americans rose fitfully at best.

As previously argued, neoliberalism is now a term of abuse, in part because of the extent to which it dominated the intellectual life of a previous era. There is no going back to neoliberalism, since it was formulated to deal with the problems of a different time, including economic crises resulting from faulty management of the monetary system. Nonetheless, the Krugman quote shows that the debate over pro-market reforms continues, sometimes in the guise of discourse over neoliberalism. From that perspective, it is worth looking at the arguments of critics who say that the reforms of the 1970s and 1980s failed. We will see that they did not, and there is in fact every reason to believe that classical liberalism is still relevant today, providing a guide to policy going forward.

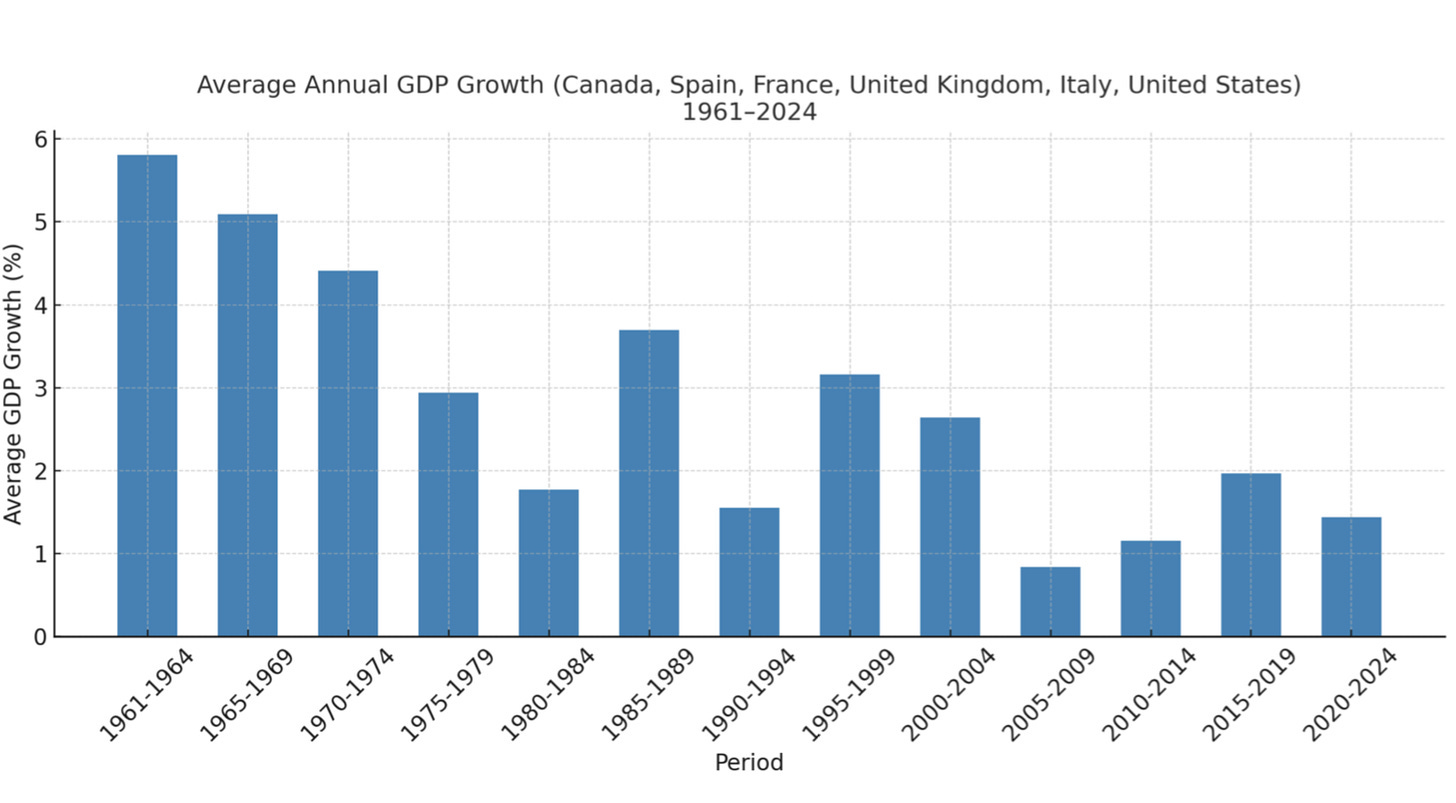

Krugman’s presentation of the data is correct. The chart below portrays average annual growth in four- or five-year intervals in six major economies: the US, UK, France, Canada, Spain and Italy. Data is from the World Bank.

Unfortunately for Krugman’s argument, in the fifteen years since he wrote the words above, the US has diverged more from Europe and large red states have seen a boom relative to blue states. While it is true that no major advanced country has returned to the growth rates of the 1950s and 1960s, the European Union in terms of tax and regulation policy is much closer to Krugman’s preferences than the US is. And yet things have not worked out nearly as well there.

In 2010, Krugman wrote “the European economy works; it grows; it’s as dynamic, all in all, as our own.” He noted that while the US grew at an average of 3% since 1980 compared to 2.2% in Europe, when you looked at per capita rates, the US lead was only 1.93% a

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.