How to See the Dead

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Visible spectrum

12 min read

Linked in the article (12 min read)

-

Retinal implant

13 min read

The story centers on building advanced retinal implants and visual prosthetics. This Wikipedia article provides real scientific context for the fictional technology, covering how actual retinal implants work, their history, and current capabilities - grounding the speculative fiction in existing science.

-

Phosphene

13 min read

The article explicitly mentions phosphenes ('those little squiggles of light that come when you rub your eyes') as the baseline for early visual implants. Understanding the neuroscience of phosphenes illuminates how visual prosthetics actually stimulate perception and why higher-resolution implants represent such a leap forward.

The first question I ask my clients is, “How would you like to see the world?”

Some answers are charming; they want to see the world as an infant does, everything new and unspoiled by habit and familiarity. Some are more professionally minded and wish for magnification-enhanced, telescopic, UV, infrared, or radiation-attuned alterations that will help them with career tasks. Still, others are curious, wishing to see the world as an insect does, through thousands of hexagonal ommatidia. By far the most popular request is visual synesthesia. They want to “see the smell of cut grass” or “watch a symphony as they would a sunset.”

April’s request, however, did not make me smile. She wanted to see the dead.

“I-I’m sorry. I think that’s out of my area of expertise,” I stuttered, not unusual for me in my personal life but rare in my professional one.

“I heard you were the best,” she said.

I was surprised to feel influenced by the flattery. Just last year, I had built eyes for a team of commercial divers working on offshore wind farms in the Arctic. The implants filtered out the stirred-up silt by canceling the polarized backscatter patterns unique to turbidity and used a low-power LiDAR array to render pressure-wave distortions as faint light ripples so the divers could see the approach of water currents. I was good. Still, an old mentor in Lagos had been printing and sculpting retinal implants since before I’d started undergrad. She’d once wired a drone pilot’s prosthetics directly into night-vision satellite feeds, so I wasn’t the best.

“It doesn’t matter how good I am,” I said. “If Newton couldn’t crack the afterlife, neither can I.”

“I know,” she said matter-of-factly. “I don’t want to see the dead continuously, just sometimes.” She sat straight-spined and kept her eyes on mine.

“Haven’t you ever lost anyone?” she asked.

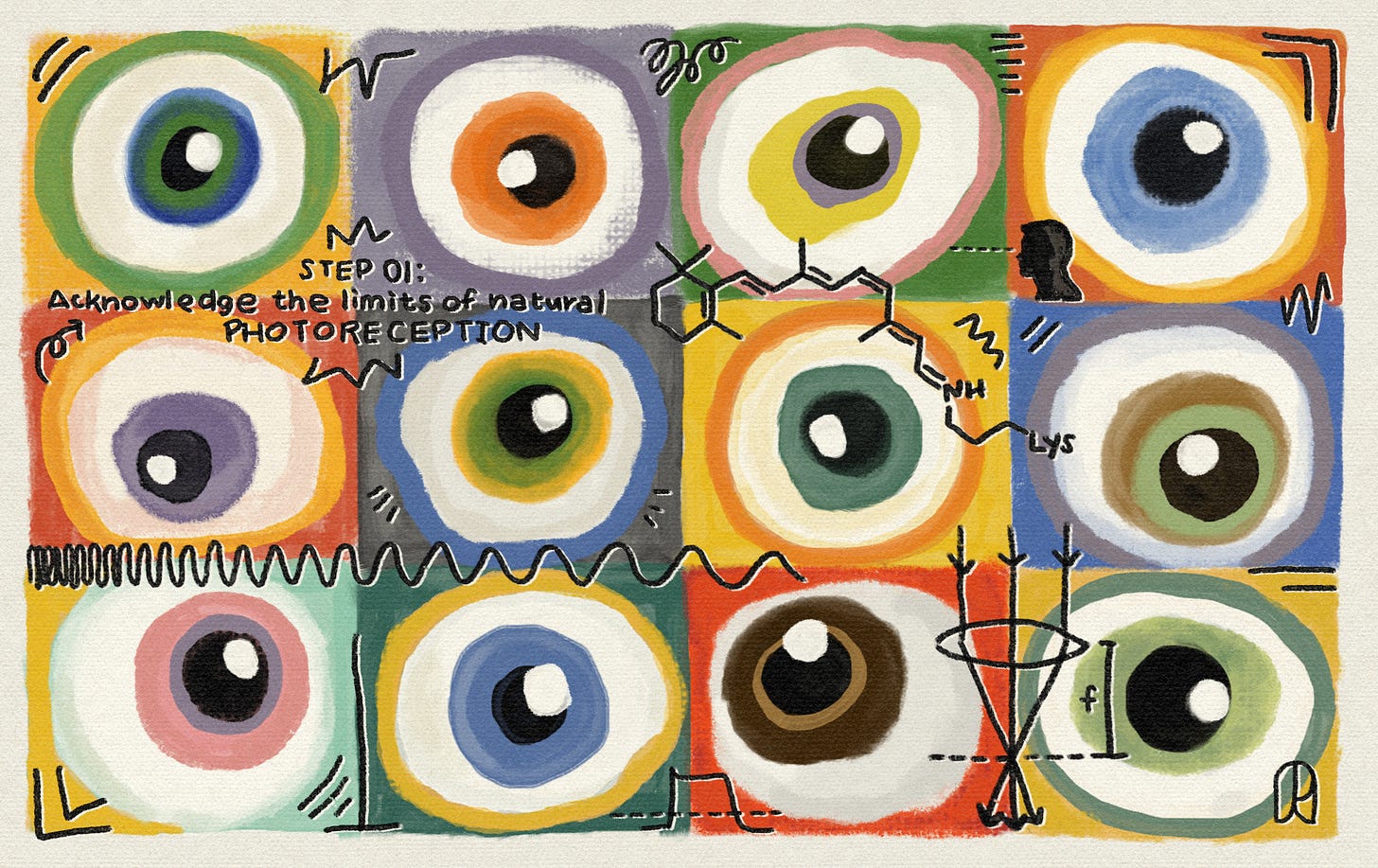

Step 01. Acknowledge the Limits of Natural Photoreception

Beneath the white glow of the lab lights, my gloves stuck to a polymer bench liner as I eased a latticed disk of organoid-grown photoreceptors from the incubator. It took hours of programming and careful printing to beat what nature equips us with naturally; eyes that can only detect a narrow 380-750 nanometer range of light. Trays of half-formed retinal cups floated in culture baths nearby.

Fifty years ago, the best visual-cortical direct-to-brain implants were only capable of translating

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.