Making the Electron Microscope

Biological structures exist across a vast range of scales. At one end are whole organisms, varying in size from bacteria only a few micrometers across to mammals measured in feet.1 These can be seen with the naked eye or with simple light microscopes, which have been in use since the mid-1600s. At the smaller end, however, are atoms, amino acids, and proteins, spanning angstroms2 to nanometers in size.

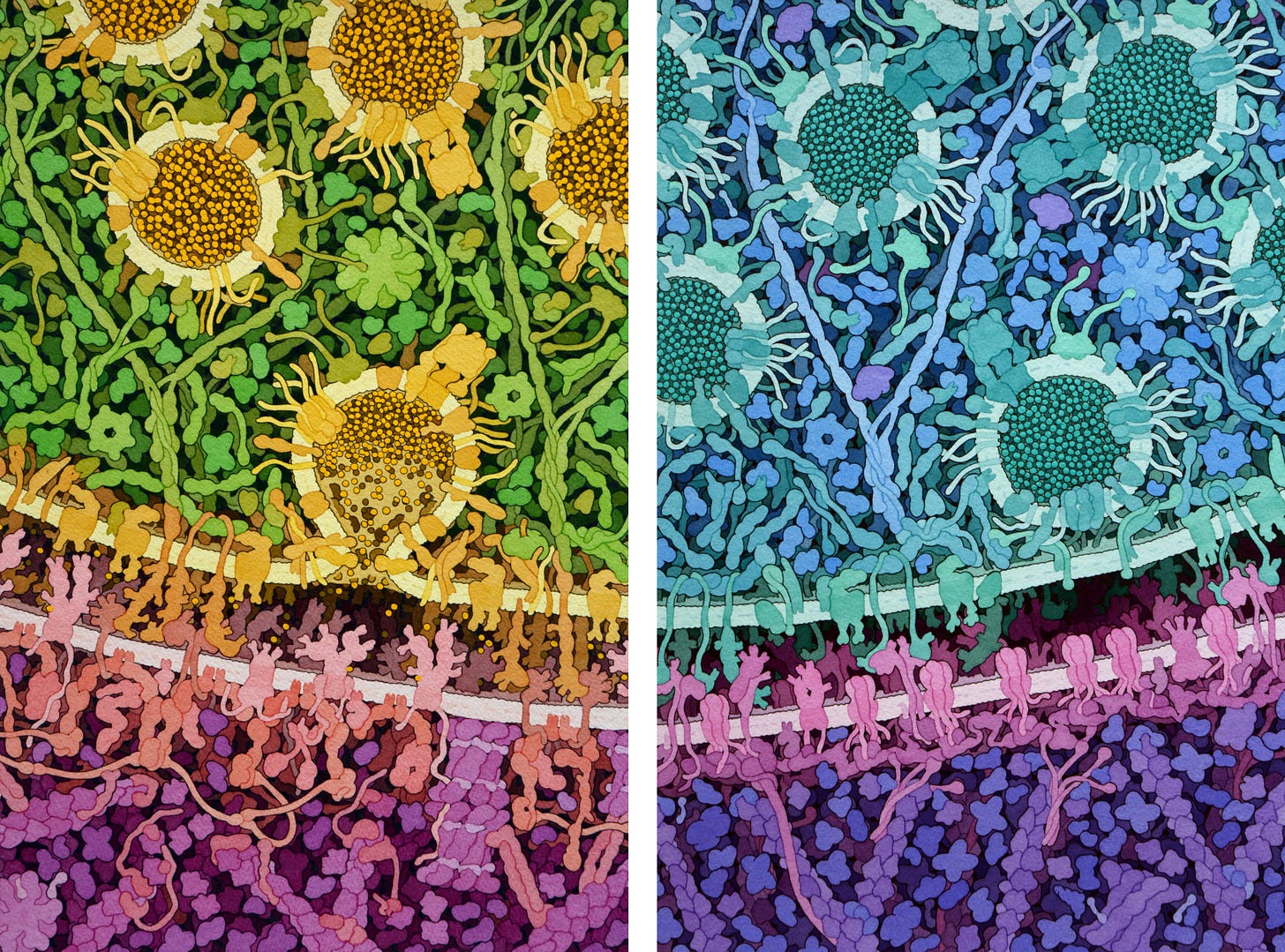

Observing molecules at this smaller scale allows us to untangle the finer mechanisms of life: how individual neurons connect and communicate, how the ribosomal machinery translates genetic code into proteins, or how viruses like HIV invade and hijack host cells. Resolving fine structures, whether the double membrane of a chloroplast, the protein shell of a bacteriophage, or the branching architecture of a synapse, provides the bridge between atomic detail and whole-organism physiology, taking us from form to function.

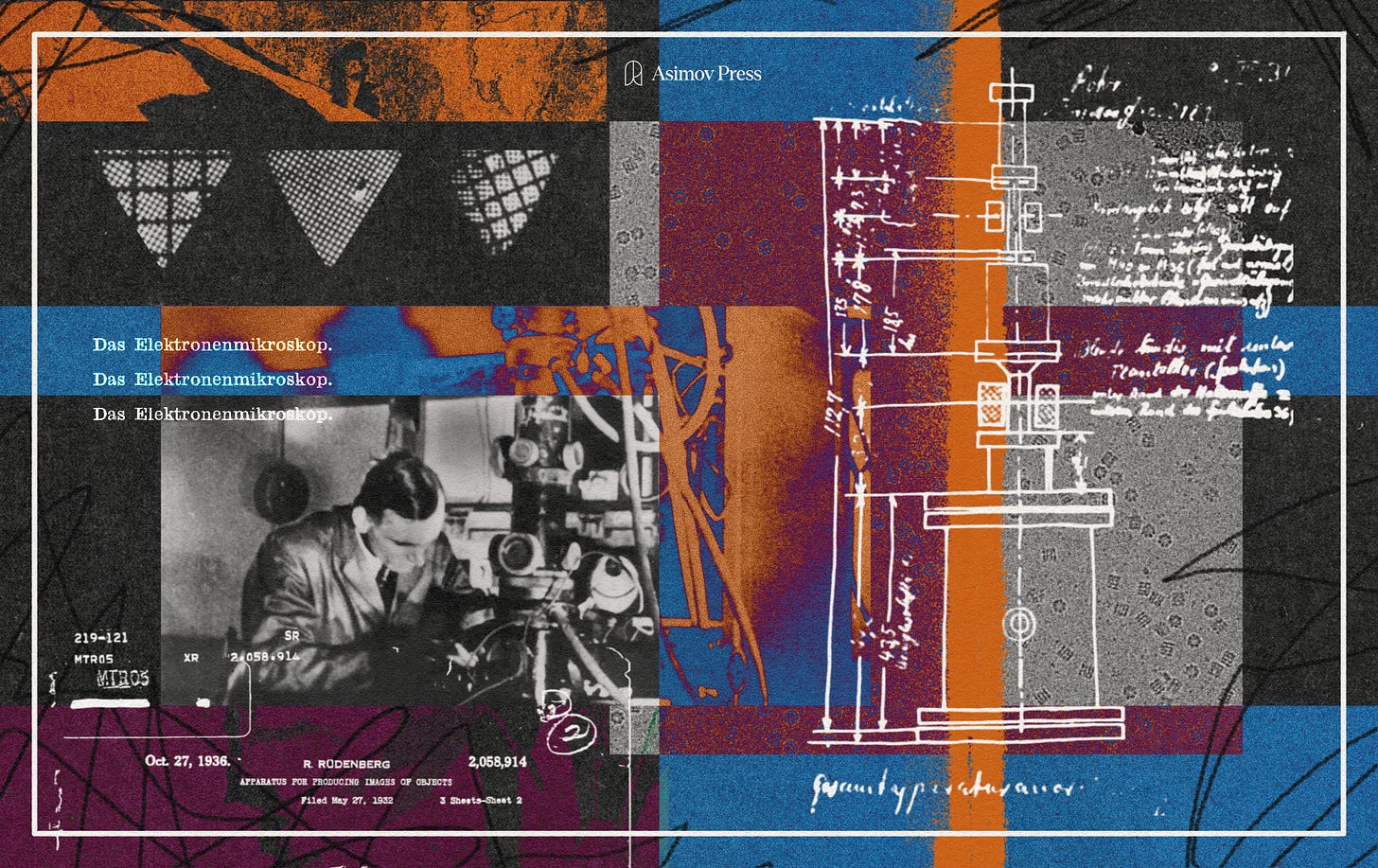

The ability to explore and map such minute mechanisms eluded scientists until the invention of the electron microscope. Conceived in the 1930s, it promised theoretical resolutions on the order of angstroms, nearly a hundred times finer than the most advanced light microscope of that era. In 1931, Ernst Ruska and his advisor Max Knoll, working at the Technical University in Berlin, designed the first prototype by replacing glass lenses with electromagnetic coils to focus beams of electrons instead of light.

That first instrument barely outperformed a magnifying glass in terms of resolution. But over the next century, refinements in design, sample preparation, and computation transformed the electron microscope into an indispensable tool for modern biology.

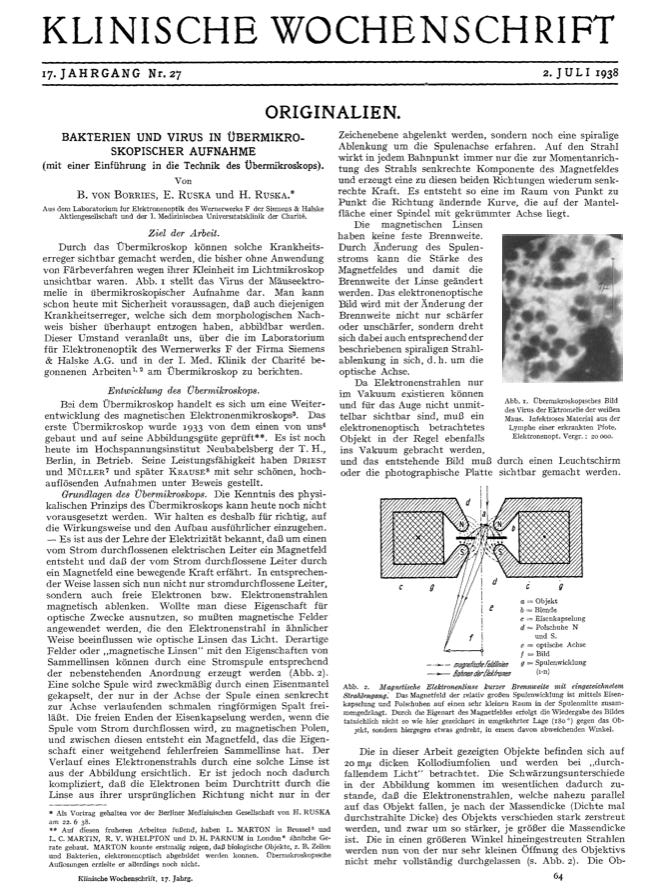

By 1938, scientists used an electron microscope to take a photograph of a virus — the mouse ectromelia orthopoxvirus — for the first time.3 And today, modern cryo-electron microscopy, in which samples are frozen in liquid ethane prior to imaging, can resolve individual atoms within proteins. During the COVID-19 pandemic, cryo-electron microscopy revealed the spike protein in the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which directly influenced the development of COVID vaccines. The technique also revealed a protein receptor that senses heat and pain, demonstrating how it translates physical signals to our nervous system, a breakthrough discovery that earned the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physiology.

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.