Thoughts on the Mirror and the Light and the Tudor Revolution in Government

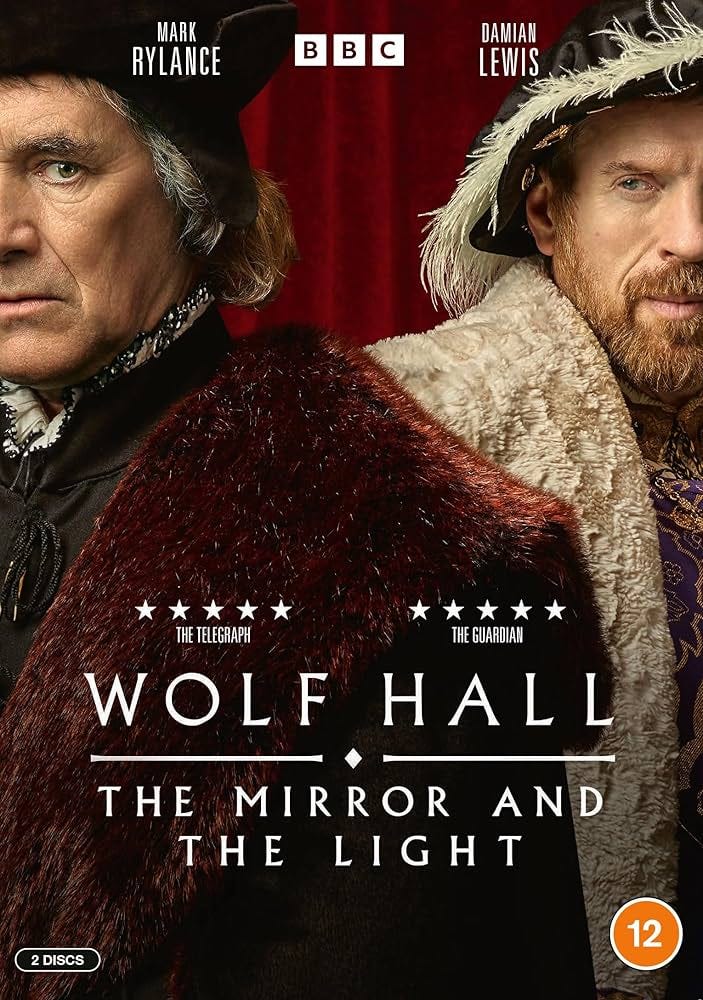

I've just finished watching the second season of Wolf Hall, The Mirror and the Light, adapted from Hillary Mantel's 2020 novel of the same name. The sets, costumes, and acting are marvelous and in keeping with the high standards set by season 1. Nonetheless, as a treatment of Cromwell and his historical role, it didn't live up to my expectations. It wasn't quite the show I wanted it to be.

This post will mostly be about why, and why Thomas Cromwell matters for thinking about some of the big questions in economic history.

But first a detour about the limits of TV as a medium for understanding history.

In recent years, commentators have, I think, come to the belated realization that the "age of prestige TV" was less of a golden age than we imagined. While there have been some exceptions (like the first season of Wolf Hall), most TV series produced since 2011 (when Game of Thrones premiered) will be soon forgotten. This is especially so of many of the historical TV series. The Medici, anyone? Or Versailles?1

Why is this? One failing is that geopolitics, economics, religion and strategy are not investigated in detail. When they are depicted, they are flattened into personal antagonisms. Personal conflict and romance are easier to depict.

Despite the quality of the production, I worried that The Mirror and the Light risked falling into this trap. Too much screen time was devoted to humanizing Cromwell.

The antihero who commits terrible crimes but also loves and wishes to be worthy of love is a mainstay of modern fiction – think Tony Soprano. And Mantel's portrait of a protean, aspiring, ambitious, but also human and humane, Cromwell was a revelation. Here, we see him try his best to look after a series of vulnerable young women: Princess Mary, Queen Jane Seymour, the illegitimate daughter of Cardinal Wolsey, and his own daughter. The quality of Mark Rylance and the other actors make many of these scenes compelling. But each scene is a variation on the same theme. Dramatically, these scenes may be needed; but narratively they are constraining and restrict the scope of the historic drama being depicted.

By episode 6, I was almost won around. Cromwell's rapid fall from power is brilliantly depicted. The fragility and arbitrary nature of political power at the top of the pyramid is exposed. Cromwell's mistakes don't have to

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.