China has invented a whole new way to do innovation

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Bell Labs

15 min read

The article directly references Bell Labs as where Americans invented the semiconductor - understanding the history and impact of this legendary research institution provides crucial context for how the American innovation pipeline functioned during its golden era

-

DARPA

15 min read

The article specifically discusses 'the DARPA model' as a key American innovation in how technology gets developed and handed off between institutions - readers would benefit from understanding this agency's history and methodology in detail

-

Bayh–Dole Act

12 min read

The article mentions this 1980 legislation as a pivotal change that made it easier for university labs to commercialize research - understanding the specifics of this law illuminates how American innovation institutions are linked together

How did the screen you’re looking at right now get invented? There was a whole pipeline of innovation that started in the early 20th century. First, about a hundred years ago, a few weird European geniuses invented quantum mechanics, which lets us understand semiconductors. Then in the mid 20th century some Americans at Bell Labs invented the semiconductor. Some Japanese and American scientists at various corporate labs learned how to turn those into LEDs, LCDs, and thin-film transistors, which we use to make screens. Meanwhile, American chemists at Corning invented Gorilla Glass, a strong and flexible form of glass. Software engineers, mostly in America, created software that allowed screens to respond to touch in a predictable way. A host of other engineers and scientists — mostly in Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and the U.S. — did a bunch of incremental hardware improvements to make those screens brighter, higher-resolution, stronger, more responsive to touch, and so on. And voila — we get the screen you’re reading this post on.

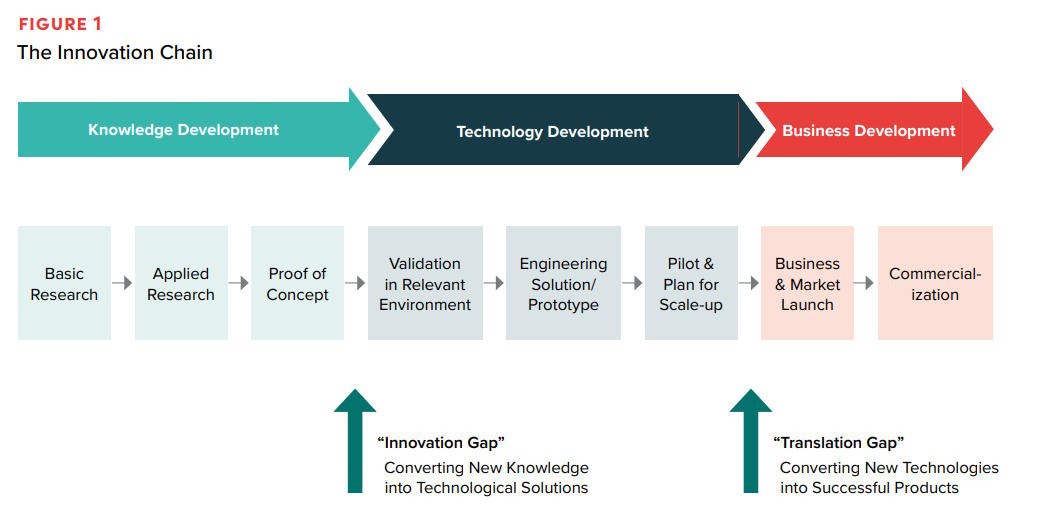

This story is very simplified and condensed, but it illustrates how innovation is a pipeline. We have names for pieces of this pipeline — “basic research”, “applied research”, “invention”, “innovation”, “commercialization”, and so on — but these are approximate, and it’s often hard to tell where one of these ends and another begins. What we do know about this pipeline is:

It tends to go from general ideas (quantum mechanics) to specific products (a modern phone or laptop screen).

The initial ideas rarely if ever can be sold for money, but at some point in the chain you start being able to sell things.

That switch from non-monetizable to monetizable typically means that the early parts of the chain are handled by inventors, universities, government labs, and occasionally a very big corporate lab, while the later parts of the chain are handled mostly by corporate labs and other corporate engineers.

Very rarely does a whole chain of innovation happen within a single country; usually there are multiple handoffs from country to country as the innovation goes from initial ideas to final products.

Here’s what I think is a pretty good diagram from Barry Naughton, which separates the pipeline into three parts:

Over the years, the pipeline has changed a lot. In the old days, a lot of the middle stages — the part where

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.