After 28 years, do Hong Kong officials really get what Beijing wants?

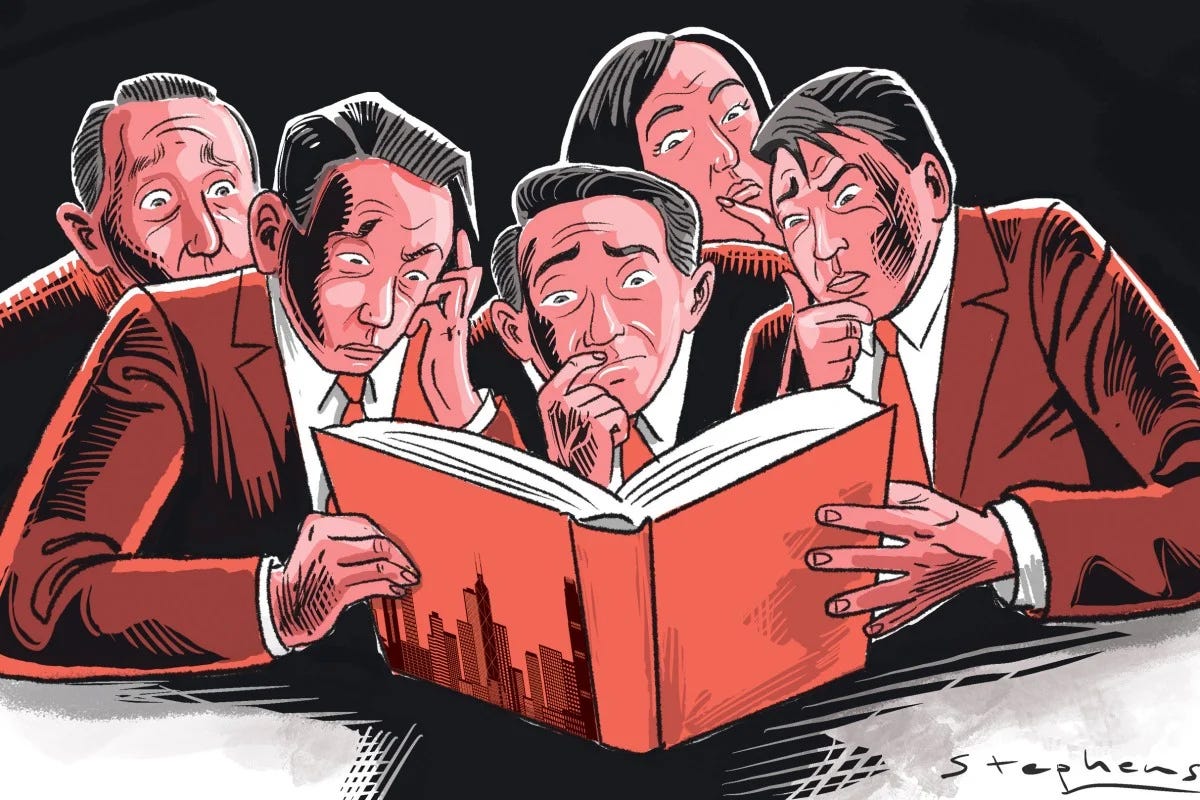

Jiang Enzhu, the first head of the central government’s liaison office in post-handover Hong Kong, famously likened understanding the city to reading a challenging book – one that demands serious attention and effort. At the time, his words served as a cautionary note to mainland officials.

Now, as Hong Kong marks the 28th anniversary of its return to Chinese sovereignty, Jiang’s analogy remains apt, though with a significant caveat. The city may still be a book that is difficult to decipher, but today’s Chinese officials may not share Jiang’s eagerness to truly grasp its complexities.

The metaphor applies both ways: for many Hong Kong residents, the intricacies of Chinese politics have proven to be just as challenging to interpret. Fully appreciating this dynamic in cross-border relations is essential to understanding what has gone awry in Hong Kong and to contemplating its future.

The stakes are high. The city stands at a critical juncture. The “one country, two systems” principle guarantees Hong Kong a high degree of autonomy and a capitalist system for 50 years. With just 22 years remaining, the city has come under increasing international scrutiny.

We can lay to rest an enduring myth from the early years: that physical proximity, coupled with the daily flow of people, goods and investment, would naturally foster deeper understanding between Hong Kong and the mainland. This assumption presumes that Hong Kong residents should possess a sophisticated grasp of Chinese politics, while Beijing should, in turn, appreciate Hong Kong’s unique cultural and economic identity.

The years have shown that reality is far more complex. Mutual understanding has arguably not deepened. If anything, misunderstandings, misjudgments and missteps by both sides have further complicated the relationship.

In the first six years after 1997, both sides – buoyed by optimism – were eager to showcase the viability of one country, two systems. Beijing saw a thriving Hong Kong as a potential model for future reunification with Taiwan. The central government’s hands-off approach was epitomised by the proverb Jiang Zemin famously quoted: “The river water does not interfere with the well water.”

Beneath this facade of stability, however, anxieties simmered. Hongkongers feared the erosion of freedoms enshrined in the Basic Law, the city’s mini-constitution, while Beijing worried about “hostile foreign forces” exploiting Hong Kong’s open society to undermine the Communist Party’s rule on the mainland.

The failed attempt in 2003 to enact Article 23 of the Basic

This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.