Growth, inequality, and the future of capitalism

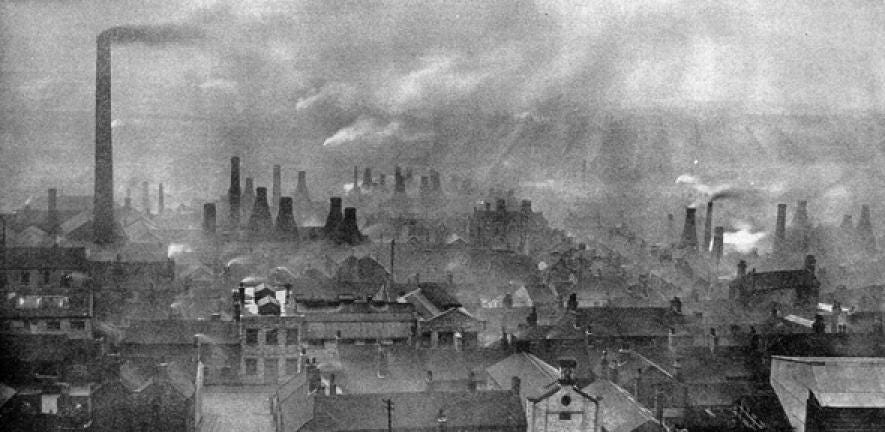

Potteries landscape, 1926. Source: Wellcome Collection. Creative Commons licence.

Been putting together some notes on growth and contemporary capitalism. There’s a definite sense, I think, in which it is now necessary to place growth as such in its context: that this was something we have had for a long period of time, but which is now looking increasingly shaky. Robert Gordon’s The Rise and Fall of American Growth does this, but obviously only for the US, and through heavy reliance on what seems to me to be an excessively speculative technological determinism. But I think we need to historicise growth: to think of economic growth not as the permanent background music of life, but as something that for most of human history scarcely existed, has enjoyed a period of two centuries or so in existence, but about which it is an intellectual error to assume will continue.

In particular, the contemporary discussion of inequality tends to think of growth as precisely something external – something beyond the question of the distribution of growth, let alone as something that may itself be contingent in human history. Thomas Piketty’s work formalises this – the famous r>g equation at the centre of his Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which says inequality will increase when the returns to wealth are above the rate of growth. But to historicise growth means not just attempting to account for its progress in the past (plenty have done this, providing GDP estimates for colossally long periods of time). It is also necessary to historicise how we think about growth and inequality, and so be able to step back a little from the background assumptions we tend to make about both.

Growth as an emerging issue

Early theories of material progress, like (most notably) those of A.R.J. Turgot, held that as technology advanced and the division of labour became more complex, society’s material output would grow – but so, too, would inequality, the inevitable result of an increasing stratification of talents and tasks. Later economists, as the discipline began to consolidate, adopted the same mechanism: Adam Smith and Adam Ferguson both had a theory of history in which civilisation itself developed through a series of increasingly complex, materially richer, but more unequal “stages” of human development, associated with a particular technology. At every point, the growth of material output meant also - inevitably - a rise in inequality.

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.