Bathtime in Bulgaria

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Ivan Vazov

11 min read

The article centers on Vazov as the 'patriarch of Bulgarian literature' and uses his bathing essay as a philosophical entry point. Readers would benefit from deeper context on his life, works, and role in Bulgarian national identity formation during and after Ottoman rule.

-

Rusalka

12 min read

The article discusses Rusalki as liminal water spirits in Bulgarian folklore alongside other threshold beings. This Wikipedia article would provide rich context on these female water spirits across Slavic mythology, their connection to liminality, and the folk practices surrounding them.

1. Readying the tub

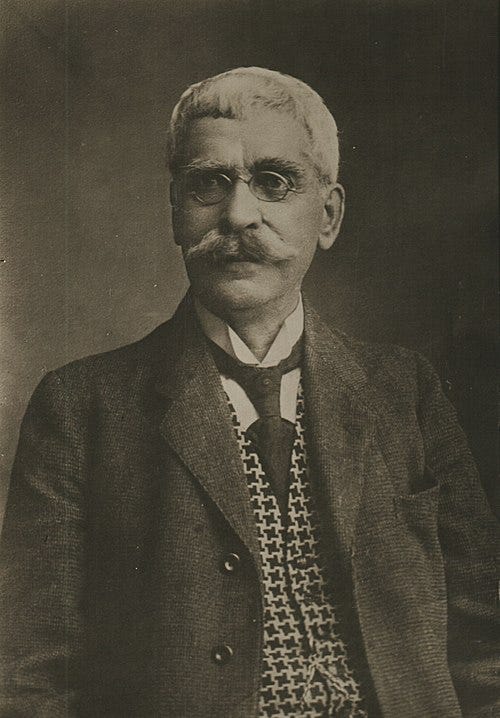

In Bulgaria, everyone knows Ivan Vazov (1850 –1921). The National Library in Sofia is named after him (Народна библиотека “Иван Вазов”), as is the National Theater (Народен театър “Иван Вазов”), along with countless parks, primary schools, streets, and squares. Statues of his likeness are scattered across the country, stern reminders of a man whose words shaped a nation.

Vazov is called the “patriarch of Bulgarian literature”, and his reputation bridges epochs: from the long twilight of Ottoman rule to the new dawn of post-liberation Bulgaria, when the country turned its gaze to Western and Central Europe. His writing provides an opportunity to think not just about this fascinating, ancient land, but about the construction of identity itself: about how we humans wrestle meaning and belonging from the sound and fury of history.

Bulgaria is a land of poets, and Vazov, though also a playwright and prolific prose writer, was most of all a poet. His fight (or at least his chosen subject) was freedom from the Ottomans. He was a comrade, at least ideologically, to more, shall we say, violent revolutionaries like Hristo Botev and Stefan Stambolov. His works rage against Turkish massacres and atrocities, and one of his most famous poems, the aptly titled “Аз съм Българче” (“I am Bulgarian”), helped usher in a new sense of Bulgarian identity: teaching children that they were born of a wondrous land [земя прекрасна], descended from a heroic people [юнашко племе]. He was, in short, the consummate 19th-century Balkan dude.

Yet, despite his power and importance, I must confess that I am not moved by his poetry. I did not grow up with his verses drilled into me, as Bulgarian schoolchildren did. My Bulgarian is good enough to follow the words but not his lyricism, his linguistic flourishes wasted on a mere novice. But Vazov is, however, quite interesting to me as a historical and philosophical figure, an entry point into the question of what it means to be Bulgarian, a way to inhabit what the philosopher Edmund Husserl called the Lebenswelt: the lived world before abstraction and conceptualization, the horizon of meaning that shapes our every action, thought, and perception.

Which is why I am not so much interested in Vazov’s verses as I am in what he did in the bathroom.

This may sound perverse, especially if,

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.