Is it a Cult? Or a Utopia?: "Auroville" by Kasia Boni

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Sri Aurobindo

13 min read

The spiritual philosopher and Indian independence activist whose teachings form the ideological foundation of Auroville. The article mentions he 'fought for independence even before Gandhi appeared' and later turned to spiritual transformation - understanding his philosophy is essential context for comprehending Auroville's vision.

-

Mirra Alfassa

14 min read

Known as 'the Mother' in the article, she was Sri Aurobindo's spiritual collaborator who actually founded and designed Auroville. The article describes her ubiquitous presence through pictures and her role in selecting the city's center - she is central to understanding Auroville's creation and governance.

-

Ryszard Kapuściński

9 min read

Mentioned as 'probably the most famous practitioner' of Polish Reportage outside Poland. Understanding his pioneering literary journalism provides essential context for the genre tradition that Katarzyna Boni's work belongs to and what distinguishes it from conventional nonfiction.

Back in the fall of 2017,1 and thanks to Polish translator Sean Gasper Bye, I had the opportunity to attend the Conrad Festival in Kraków and spend a few days talking with Polish agents, editors, authors, translators, etc.—a fairly typical editorial trip tied to an important literary festival. I love Poland, in part because both sides of my family are Kashubian, from the area near Gdansk, and as such, I feel an ancestral kinship with the country and culture, but I also absolutely love their literature. From Bruno Schulz to Tadeusz Konwicki to Olga Tokarczuk to Jerzy Pilch to Wiesław Myśliwski to Wojciech Nowicki to the reportage writers listed below, I’m a big fan and am always excited when a new Polish translation comes across my desk.2

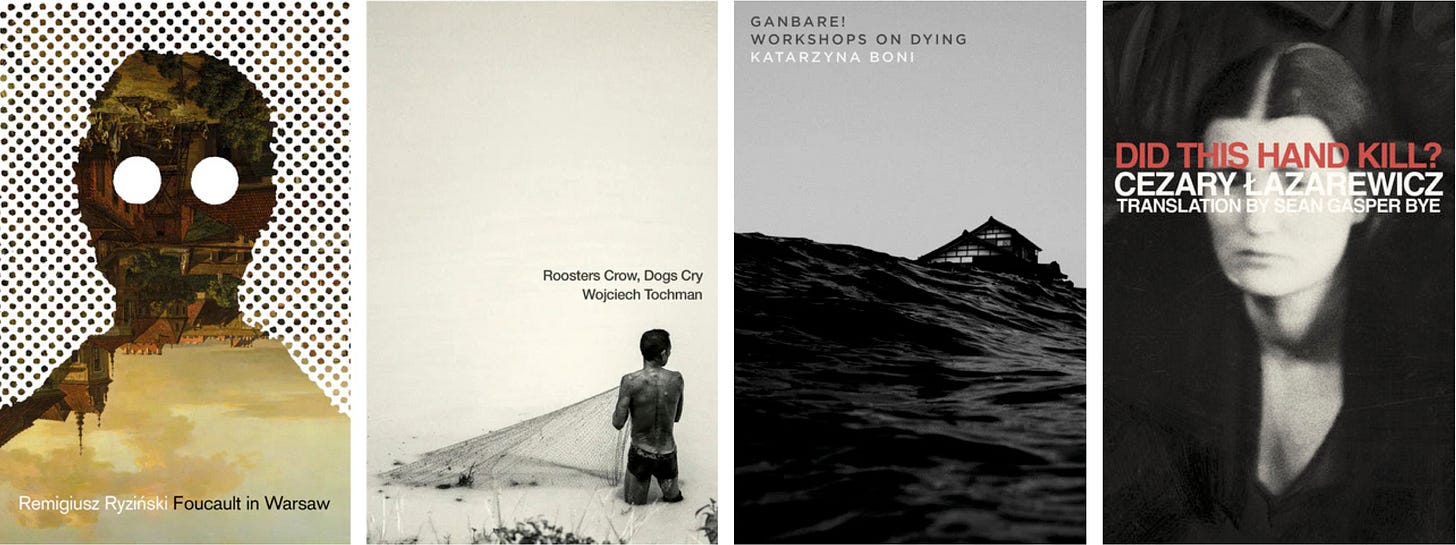

Anyway, the Big Result from this trip was the decision for Open Letter to publish a series of works of Polish Reportage, starting with five titles over five years, and then expanding outward. Before getting into the texts—and, specifically, Auroville—I want to publicly thank Sean Gasper Bye and Antonia Lloyd-Jones for their help with this. They were critical to selecting which titles to include, and translated the bulk of them as well.

For anyone not in the know, Polish Reportage is a long-standing Polish literary tradition that, put simply, utilizes fictional techniques in reporting on real life situations. Ryszard Kapuściński is probably the most famous practitioner outside of Poland’s borders, but Hannah Krall, Artur Domosławski, and Małgorzata Szejnert are three other big names. There is a special school to train writers in this tradition, and a huge number of books falling under the banner of “Polish Reportage” are released every year.3

Three things that I love about this type of writing (and the books we’ve done) are: 1) the subjects written about are not tied to Poland, so it’s automatically international in scope; 2) American sales reps, booksellers, and readers don’t always know what to make of this (catnip for me and my love of unique works and befuddlement), since the works are technically true and factual, but by acknowledging how the author’s viewpoint impacts the representation of the narrative (like quantum theory, in a way), these books sort of float between traditional reporting and personal essay; and 3) for whatever reason—subject plus approach—these books tend to avoid the “last chapter” problem that occurs in 95% of nonfiction

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.