Sunday Pages: "Arcadia"

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Second law of thermodynamics

13 min read

Central to Arcadia's plot - Thomasina's discovery that heat flows only one direction is a key dramatic element, and the play uses entropy as a metaphor for time's irreversibility

-

Lady Caroline Lamb

12 min read

The article mentions Hannah's bestselling book is about Lady Caroline Lamb, Byron's infamous lover whose scandalous affair and mental breakdown after their breakup remains one of literary history's most dramatic romances

-

Fermat's Last Theorem

13 min read

Fermat is explicitly mentioned as one of the play's themes - the theorem's 350-year unsolved status parallels Arcadia's exploration of mathematical proof, knowledge pursuit, and what remains unknowable

Dear Reader,

In “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead,” the insanely brilliant 1966 play that put Tom Stoppard on the literary map, the head player of an acting troupe the two titular characters meet on their way to see Prince Hamlet explains that his company is from “more of the blood, love, and rhetoric school.”

When Guildenstern asks them to choose one of the three for the performance, the player says that they are “hardly divisible…I can do you blood and love without the rhetoric, and I can do you blood and rhetoric without the love, and I can do you all three concurrent or consecutive, but I can’t do you love and rhetoric without the blood. Blood is compulsory—they’re all blood, you see.”

Thus does Stoppard broad-brush the entire catalogue of William Shakespeare.

In 1995, I had just graduated from college, found a job in the video library of an advertising agency, and was living for a few months in the Jersey suburbs with my parents. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, the film version of the play, starring Tim Roth and Gary Oldman and directed by Stoppard, had come out a few years prior, putting the playwright on our radar—“our” being me and my friend Chris, who was also living in my parents’ house while we waited to move to an apartment in Hoboken.

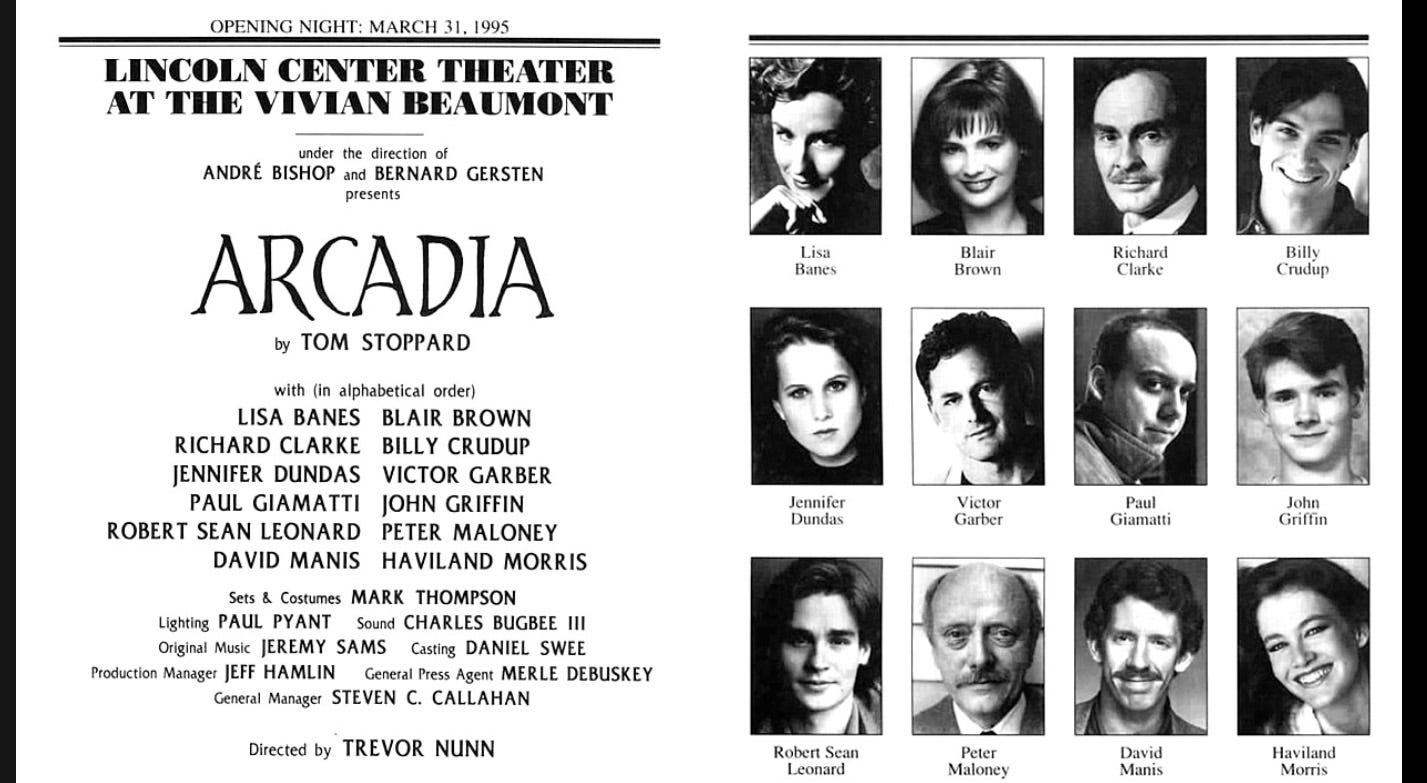

That was the year, and the season, that Stoppard’s new play, “Arcadia,” opened at Lincoln Center. And we must have hung around the city after work one summer day and taken in the show during the week, because according to Playbill, the play only ran from March through the end of August 1995—and I definitely saw it.

But then, my memory is faulty. I also recall that the actor playing Septimus Hodge was a dashing young Rufus Sewell. But no less an authority than the World Wide Web has it that, while Sewell originated the role in the London production, he didn’t come to New York; the Broadway production starred an also-dashing Billy Crudup. But why, if I had not seen Rufus Sewell in “Arcadia,” would I remember the name Rufus Sewell, long before Rufus Sewell came back into my consciousness playing the American Nazi in The Man in the High Castle? Was there another, subsequent Broadway production of “Arcadia” that Google has memory-holed? But no—I distinctly remember us being interested in seeing

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.