The Moral Brain

Over the last few months we’ve gone through a meandering journey here at Synapse to uncover the psychological nature of morality in an effort to understand why people make different moral judgements. In Toward a Quest of Understanding, I outlined evidence that our moral decisions are more about our emotional thinking than our rational thinking. Jonathan Haidt likens this phenomenon to the Elephant (emotions) and the Rider (reason). The rider of an elephant often appears to be in charge, but if there is a disagreement between the elephant and the rider, the elephant will win.

Then, in Beyond WEIRD Morality, I wrote about the rather narrow view of morality that the scientific literature portrays. How are we to understand the true nature of morality if the people we use in studies are disproportionally from western, industrial, democratic, and individualistic societies?

Last week, I presented one theory of morality that attempts to be more inclusive of the diverse moral tastes we find in humans across the world (by the way, I’ve gotten lots of great feedback on this piece, so keep sending it in!).

This week, I hope to leverage more neuroscientific studies to fill in gaps about how our moral brain works before moving on to a different topic. So here goes…

How does morality work in the brain?

In 2013, Pascual, Rodrigues, and Gallardo-Pujol reviewed the current neuroscientific research on how the brain modulates moral decision making. From a scientific perspective, this topic is typically studied by presenting subjects with moral dilemmas while scanning the activity going on in their brains. The most famous moral dilemma used in this study is the trolley problem in which subjects are asked to make a choice between killing one person or letting five people die.

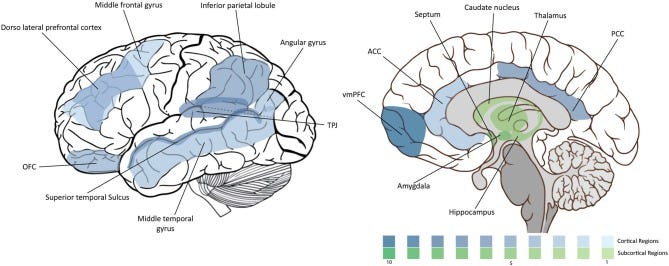

One interesting insight from this review is the implication of two brain areas: the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC).1 The VMPFC seems to play a key role in the emtional side of moral judgements. For example, patients with damage to the VMPFC are more likely to endorse a utilitarian solution to a hard moral dilemma.2 The DLPFC, on the other hand, seems to be more strongly activated in rational side of moral judgements. For example, the DLPFC is

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.