Give me a beer, stick a candle in it, and I'll blow out my liver

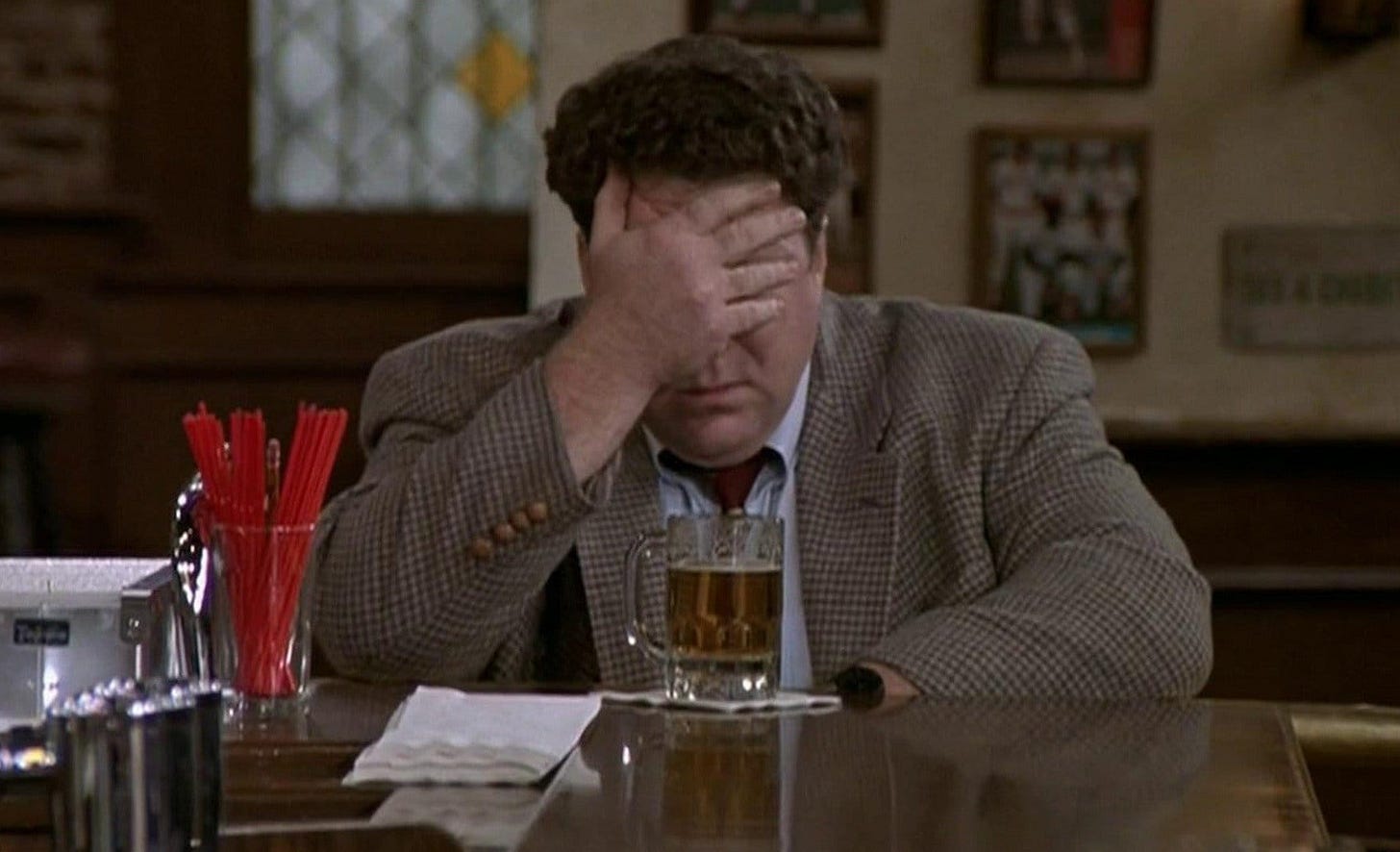

When the weight of the world has got you down, and you want to end your life—bills to pay, a dead-end job, and problems with the wife—well, don’t throw in the towel, because there’s a place right ’round the block where you can drink your miseries away.

Wait. No, that’s the Flamin’ Moes song. This is a piece about Cheers.

But I suppose it’s only appropriate that I once again open with The Simpsons. If my childhood awareness of M*A*S*H was due to re-runs, which led into The Simpsons on weekday afternoons, then my awareness of Cheers was based almost exclusively on the animated series’ parodies of it.

I was also aware of its reputation: it consistently tops, or nearly tops, lists of the greatest sitcoms ever made, regularly edging out M*A*S*H and, somewhat less regularly, Seinfeld. (On the last such list I read, it came second to—what else?—The Simpsons.) But unlike M*A*S*H, I had never seen an episode until recently. For whatever reason, Cheers wasn’t really syndicated here. (My first exposure to Ted Danson was through Three Men and a Baby and its sequel, and, on television, Becker. These are not the sort of productions that send one racing to the archives for more.) In any case, after finishing M*A*S*H in its entirety a couple of months ago, I decided to give Cheers a try.

The show arrives fully formed. Not only does it know, from the moment it begins, exactly what it wants to be, it also manages to be that thing, or at least a very convincing version of it. The thing in question is a 1930s or 1940s romantic comedy, with sexual chemistry and cutting dialogue providing the momentum that a plot usually might. (The show doesn’t leave the bar at all during its first season and I am honestly at a loss to recall a single actual story from it.) The show’s creators—Glen Charles, Les Charles, and James Burrows—liked to cite Tracey and Hepburn as their models, but what I am reminded of, when I watch Sam and Diane, is His Girl Friday, with Danson in Carey Grant’s role and Shelley Long in Rosalind Russell’s. Watch any of their verbal sparring matches—not least the lengthy, contentious one that ends the first season—and note the way their bodies advance, ostensibly in the interest of saying

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.