Solving a 25-year-old genetic puzzle

I hope your week is off to a great start! The past few days, I’ve been digging into the Spinocerebellar ataxia type 4 (SCA4) literature, inspired by a new Nature Genetics paper on the successful mapping of the causative gene and mutation underlying SCA4. I've read this work last year when it was preprinted and tweeted about it. I've mentioned this preprint in a couple of my past substack posts in relation to long-read sequencing, and discussed it in the Genetics podcast with Patrick Short. But rereading the paper in its final published form helped me see that there are more interesting things buried in the SCA4 literature, which I didn't notice before.

My interest in the repeat expansion-related neurodegenerative diseases has been growing recently, as there are currently many active efforts in the field to develop therapeutics for these conditions. With the recent advancements such as long-read sequencing, single-cell sequencing etc., researchers are beginning to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying neurodegeneration (for example, cell type specific somatic expansions of repeats and how they kill the striatal neurons in Huntington's disease) and ways to prevent them (for example, targeting DNA repair genes to halt the pathological repeat expansion). So, I might be digging more into the repeat-expansion literature in the near future.

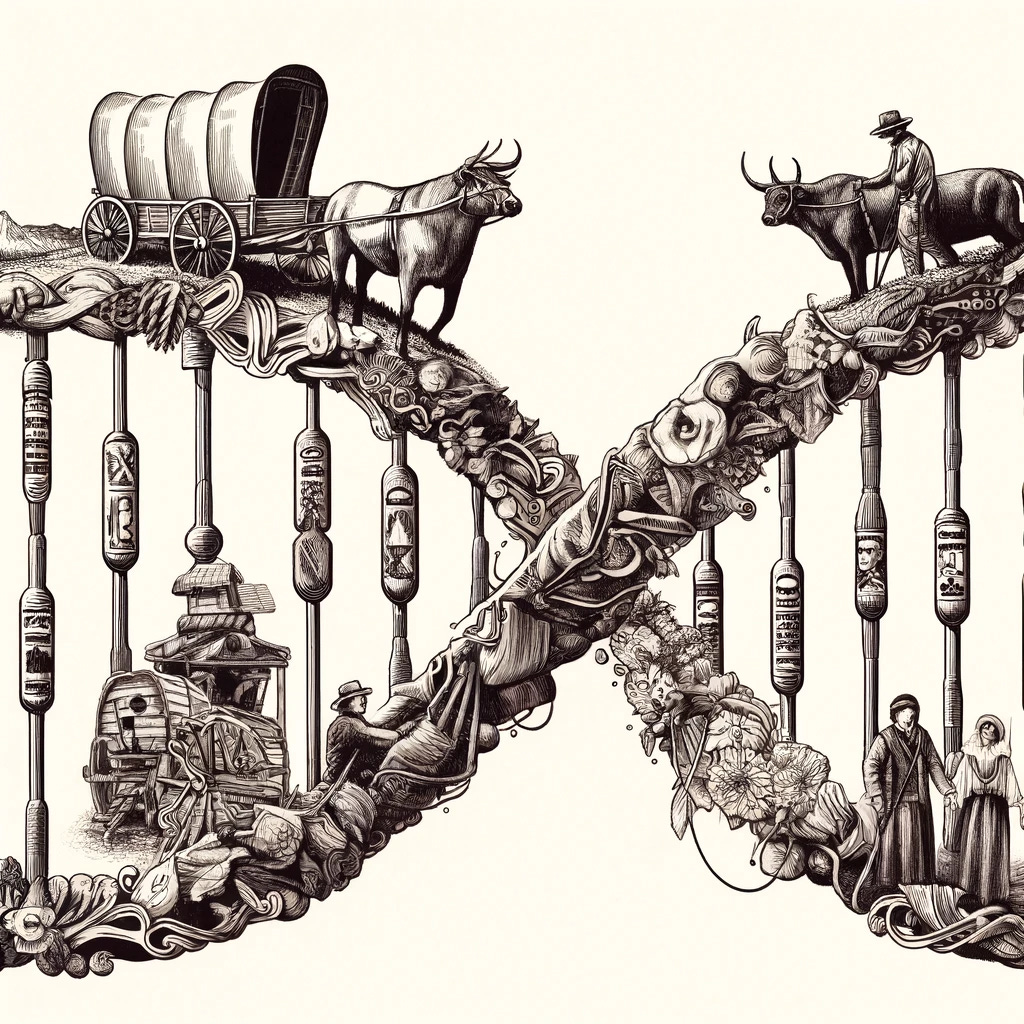

The fact about SCA4 that caught my attention was that its cause remained a mystery for more than 25 years due to high complexity of the SCA4 locus (16q22.1), and then long-read sequencing technology helped scientists to identify the disease gene (ZFHX3) and mutation (expanded GGC repeats). But there is more to the story.

At least four independent groups have successfully mapped the GGC repeat expansion in ZFHX3 to SCA4: one group from the University of Utah (where the index family was first documented in 1994, the linkage to 16q22.1 was mapped in 1996, and the ataxia was officially labelled as type 4), two groups from Sweden (one from the Lund University and the other from Karolinska Institute) where the pathogenic mutation was believed to be born in some family in Southern Sweden, possibly in the early 19th century. And the last group of researchers were from University College London and University of California.

Amazing, isn't it? After the initial linkage

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.