Two Artists, Linked Across Distance

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

National Film Board of Canada

14 min read

Chartrand worked as an animator and later director at the NFB, which funded Black Soul. The NFB has a unique history as a government film producer that has nurtured experimental animation for decades, providing important institutional context for how this film came to exist.

-

The Old Man and the Sea (1999 film)

10 min read

Alexander Petrov's Oscar-winning paint-on-glass adaptation of Hemingway's novella represents the culmination of the technique Chartrand traveled to learn. While not explicitly mentioned in the excerpt, it's Petrov's most celebrated work and directly relevant to understanding his mastery that inspired Chartrand.

Welcome! It’s another Sunday issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s what we’re doing today:

1) Black Soul, and the friendship between two animators.

2) Animation newsbits.

With that, let’s go!

1 – Studying abroad

A video blew up this week. It’s a clip from Black Soul, a Canadian film released 25 years ago. We posted it on social media — and the musician Aïsha Vertus shared it. “That’s my auntie who made this film,” she wrote. “She’s a genius!”

The clip reached hundreds of thousands of people from there.

It was surprising. Black Soul is a beautiful film, but it’s not flashy in the way that tends to get attention on social media. It’s a trip through history — a kaleidoscopic one that morphs from scene to scene. The film’s director called it “a wordless tribute that traces the history of Black people, from the beginning up to the present.”1

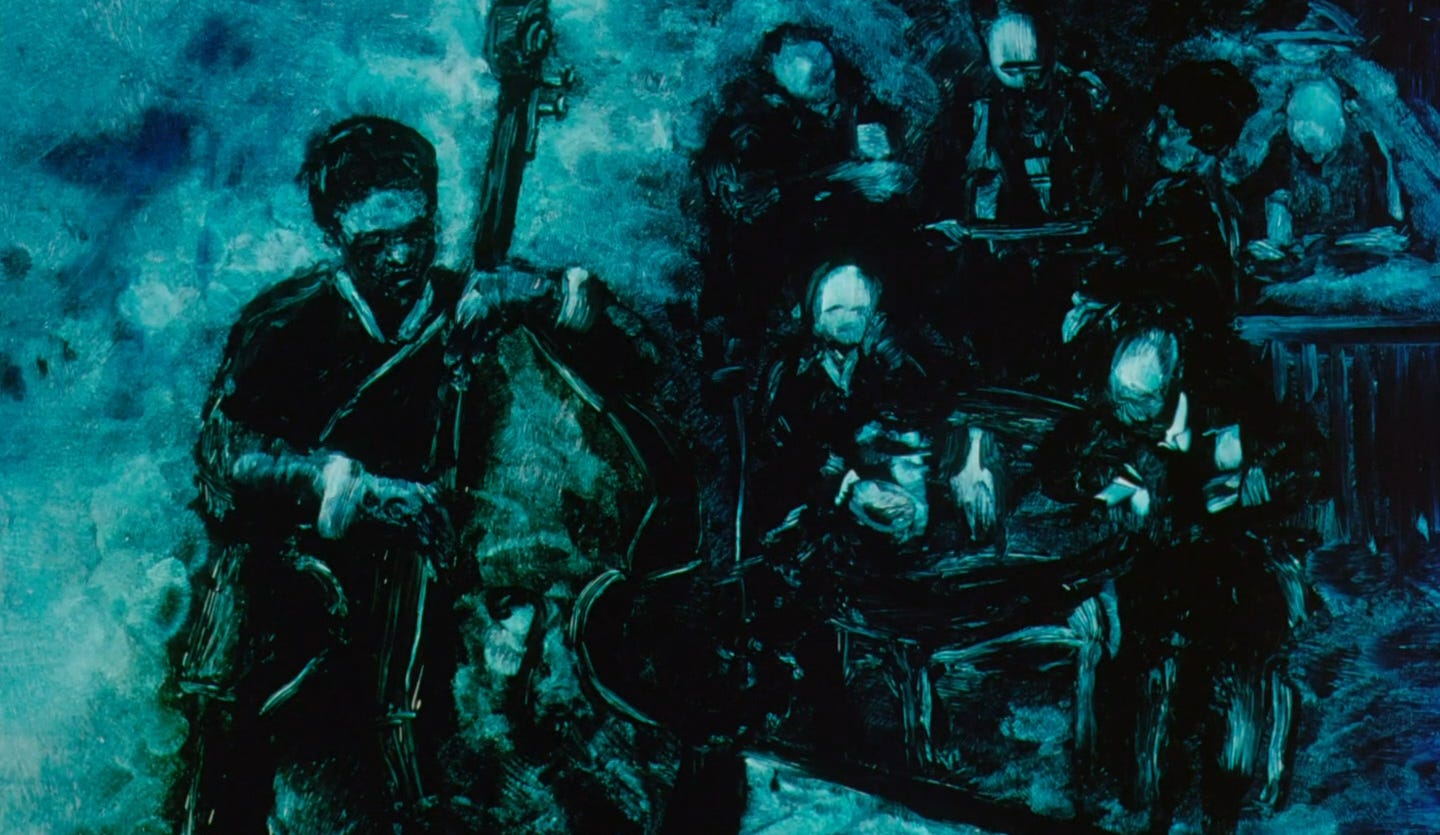

That director’s name is Martine Chartrand, and she animated Black Soul with oil paint on glass. Creating it took seven years, including roughly “five-and-a-half years of animation,” she’s said. Chartrand painted it mostly with her fingers, using the less toxic oils produced by Holbein and Rembrandt. At times, she found herself in her dimly lit workspace “seven days a week.”2

Once finished, the film quickly turned into a big deal — it even won a Golden Bear in Berlin.3 No Canadian short had taken that prize since the ‘80s.

For Chartrand, the project was the fulfillment of a dream. A key part of this dream was the technique she used. In the early ‘90s, she’d been changed by an encounter with the painted animation of Alexander Petrov. The two artists lived in separate worlds — Petrov worked in the USSR at the time. But Chartrand decided that, somehow, she would become his student.

And she did.

When Alexander Petrov rose in the ‘80s, paint-on-glass animation wasn’t new. It’d appeared in films like Horse from Poland and The Street by Caroline Leaf, made during the ‘60s and ‘70s. Artists in Germany had used it as early as 1921.4

But Petrov’s approach was fresh. His first painted masterpiece was The Cow (watch), a student project from ‘89. It was something remarkable. When

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.