Book Review: The Road to Wigan Pier

There are a number of authors whose influence on We Have Never Been Woke is super clear. Sociologists Max Weber, Pierre Bourdieu and Shamus Khan spring immediately to mind. Or Bruno Latour, whose We Have Never Been Modern inspired the title of my own book, and whose symmetrical and charitable modes of analysis deeply informed my own approach (more on this point here).

Jean Baudrillard is rarely mentioned but looms heavily in the background. Foucault as well. Indeed, one of the main contributions of We Have Never Been Woke to the literature on the rise of the symbolic economy is its focus on power: who has it, how is it deployed, in the service of which ends and under what auspices?

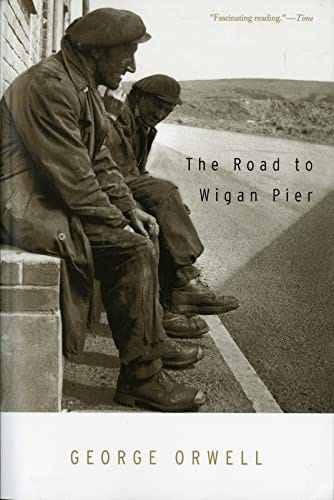

George Orwell was a major influence too. I cite his essay “Why I Write,” in the introduction while explaining my own motivation to pen We Have Never Been Woke. Orwell’s advice in “Politics and the English Language” is a clear influence on my own style. However, the book by Orwell that most directly influenced my thinking on the Great Awokening(s) was The Road To Wigan Pier – a book that feels as timely as ever nearly 90 years after its publication.

Some Background

The Road to Wigan Pier was initially commissioned by the Left Book Club to document the plight of workers in Northern England during the interwar period. Orwell faced two core obstacles in helping symbolic capitalists in hubs like London understand the working class everywhere else:

Very few people in his target audience had ever held a non white-collar job. Most of his socialist readers had been born relatively well-off and were currently relatively affluent. The experiences of manual labor, chronic unemployment and poverty were totally alien to them.

His audience, despite their socialist leanings, tended to hold negative and inaccurate views about “those people” sociologically distant from themselves – limiting their sympathy to the plight of workers. They romanticized “the proletariat” in the abstract but detested the working class in practice.

In order to get over the first obstacle, Orwell provides a “thick” ethnographic description of workers and their lives. He stays at the kinds of hotels single coal miners sleep in; he treks through the mines (an extremely arduous journey each way), observes them at work, and reports on the risks they face. He describes workers’ living

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.