And the 2025 Economics Nobel Goes to...

There are years when the Nobel prize in economics is good, years it is bad, and years it is outstanding. This year is outstanding. This is the prize I’ve been waiting for. Not because I predicted it or had money riding on it, but because it recognizes work that tackles THE question: Why did we get rich?

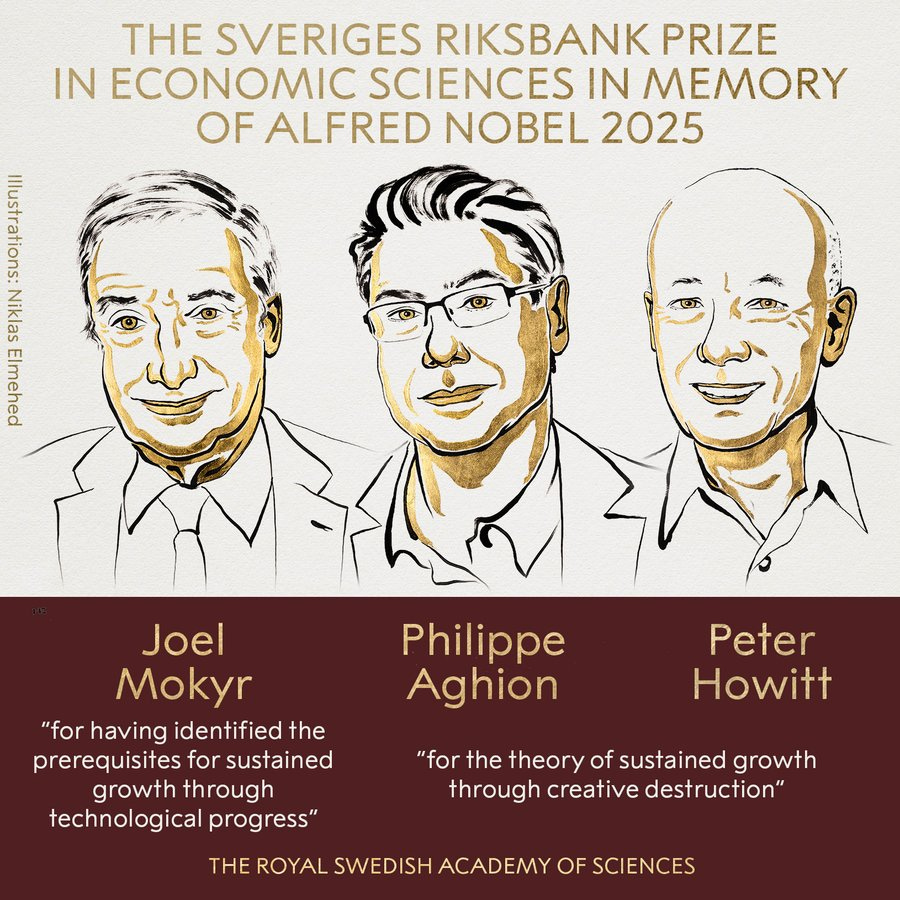

The 2025 Economics Nobel went to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth.”

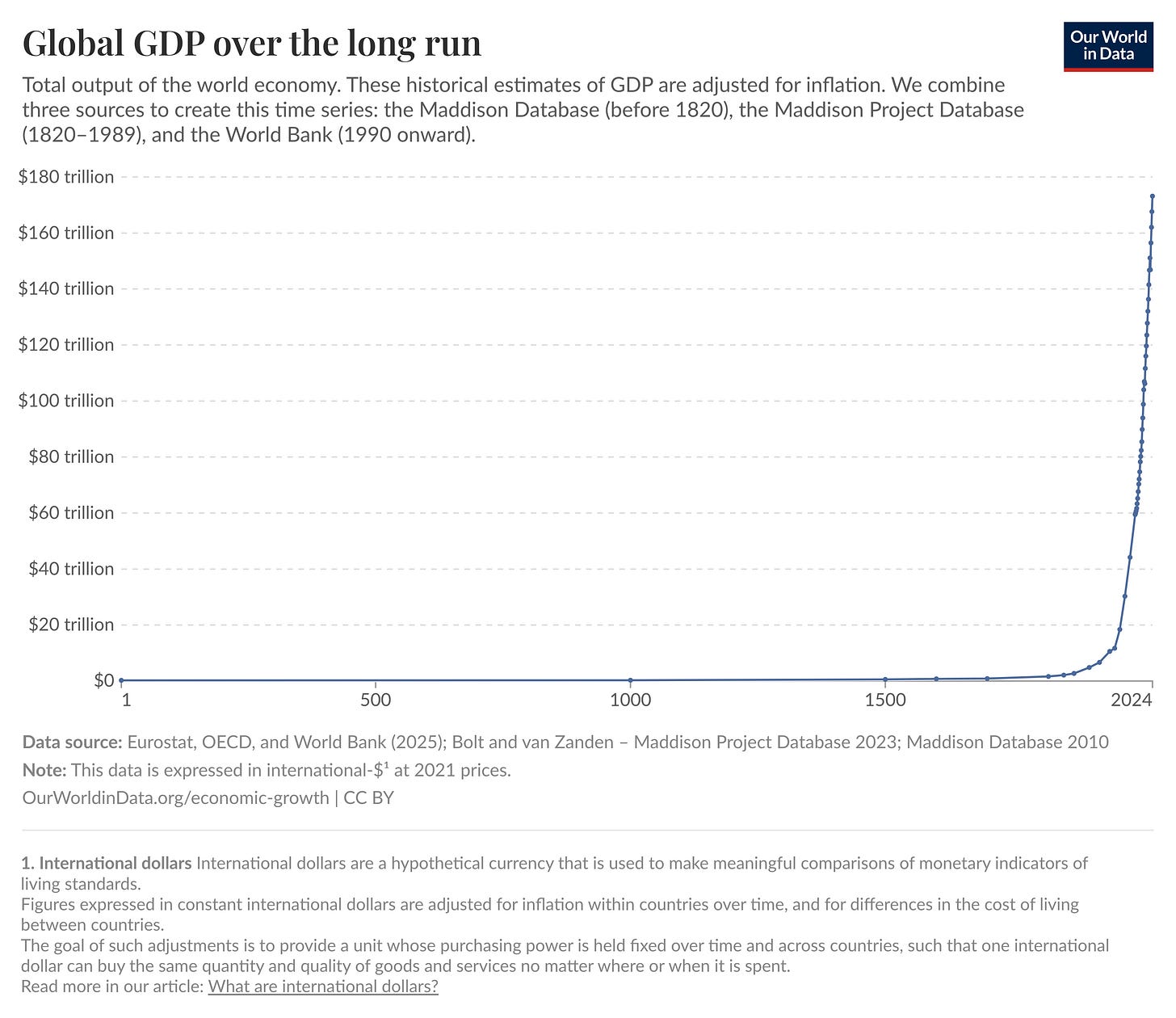

The biggest question in economics is the hockey stick. For most of human history, living standards barely budged. Then something shifted. We got the hockey stick. Why did this happen? When? What made it possible? Many economics papers are small. Many of my papers are small. But not this work.

This prize splits among two different contributions. Mokyr gets half for explaining the prerequisites—what conditions needed to exist before sustained growth could happen in the first place. Aghion and Howitt share the other half for building the workhorse model of how innovation actually drives growth once those conditions are met. It’s history meets theory. Last year’s prize was history and theory but this is actually history. And that’s how economics should work.

The Intellectual Origins of Economic Growth

Mokyr, compared to the other two, really won for a body of work on the topic. Mokyr’s research program spans decades and fills multiple books, so it’s not simple to say what his argument is. To understand his argument, you need to trace its development across his major works.

His most cited work (maybe because it was earlier) is The Lever of Riches (1990), where he established the framework by asking why technological progress occurs at all. Mokyr argued that neither demand-pull nor supply-push theories alone could explain innovation patterns. Instead, he introduced the concept of “macroinventions” (radical breakthroughs) versus “microinventions” (incremental improvements), showing how both were necessary and how their relative importance varied across societies and eras.

In The Gifts of Athena, Mokyr develops his central analytical distinction. There are two types of “useful knowledge” necessary for innovation:

First, there’s propositional knowledge, understanding why things work. The scientific or theoretical principles behind natural phenomena. This includes mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, what Mokyr calls the “epistemic base.” Think of it as “knowing that.” This is the science stuff, understanding that air has weight and pressure, knowing the principles of combustion, recognizing that diseases spread

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.