Why no one likes land taxes

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Henry George

13 min read

The article directly references Henry George's 19th-century 'Single Tax' movement on land values, which is central to understanding why land value taxes were never widely implemented despite their theoretical efficiency

-

Gary Becker

13 min read

The Becker-Mulligan model is one of the two main theoretical frameworks explained in the article. Understanding Becker's broader work on applying economic analysis to political behavior provides essential context

-

Deadweight loss

12 min read

The entire article hinges on the concept of deadweight loss and why 'efficient' taxes with low deadweight loss paradoxically lead to larger government extraction. Readers need to deeply understand this economic concept to follow the argument

Economists and [insert basically every other group of people] don’t often agree. Take, for instance, the recent discussion of price controls. The title of Sunday’s NYT opinion piece literally starts “Economists Hate This Idea.” Yet voters aren’t so skeptical. (I’m not ready to say it has the popularity that piece claims.)

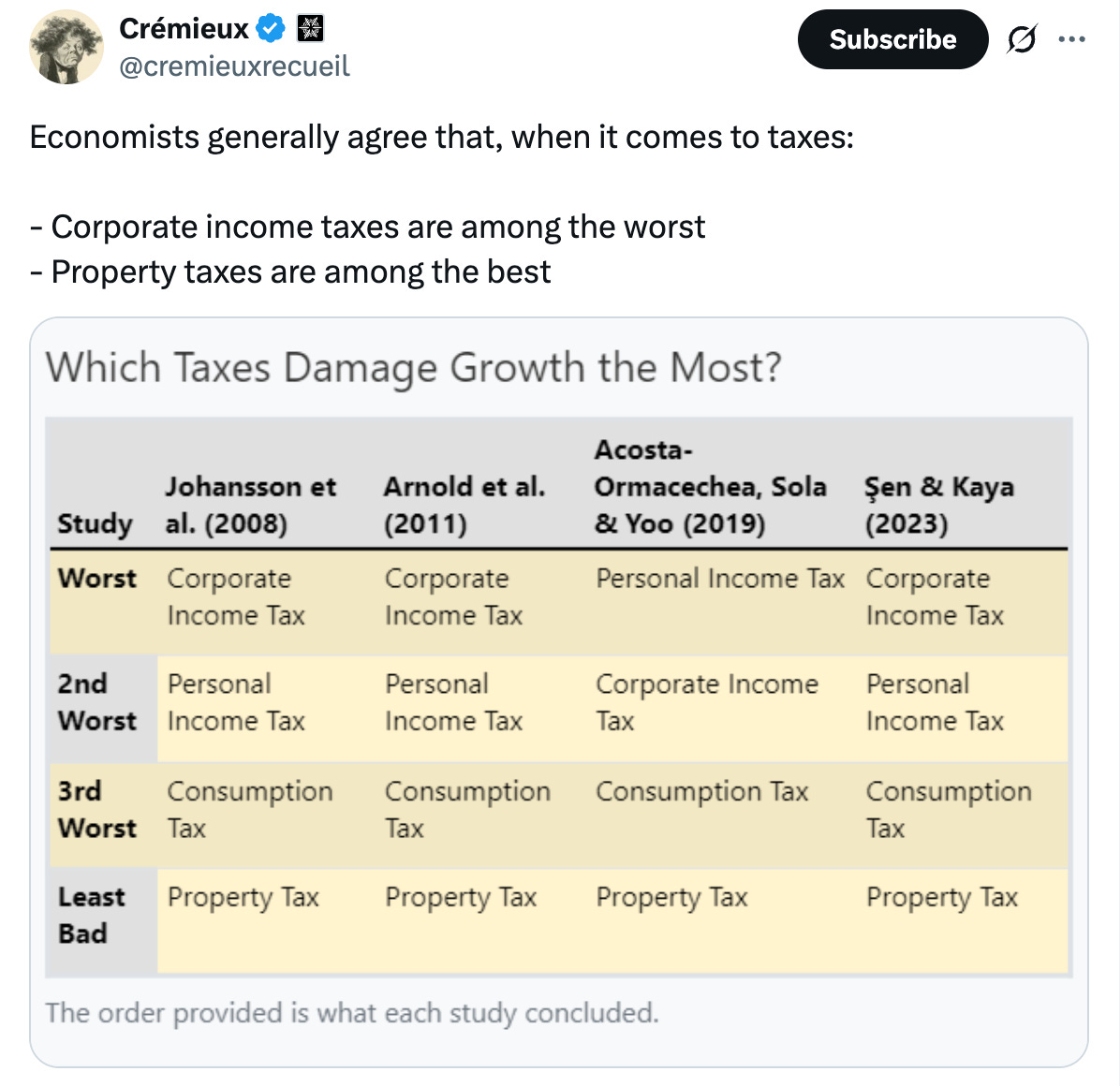

Another area of disagreement is taxation. Economists tend to prefer taxes like property taxes; voters despise them. Economists think corporate taxes are among the worst ways to raise revenue; voters think corporations should pay more. Economists generally prefer consumption taxes to income taxes, whereas voters tend to prefer income taxes.

I say “prefer” and “think,” but it’s not just some whim. It pops out of many models and there’s research pointing in the same direction.

Byrne Hobart recently started a great piece with this puzzle. Ask an economist about property taxes, and they’ll explain that the land part is fixed in supply (not much distortion there), impossible to hide, and therefore ideal to tax because taxing it doesn’t distort behavior. Ask a median voter about property taxes, and you’ll hear complaints about paying rent to the government on something they already own. As Hobart puts it, “the things voters hate about property taxes are the things economists love about them.”

If I’m being honest, the standard economist reaction is to be dismissive of voters. Economists when being more careful will say voters are “rationally irrational,” since one vote rarely decides an election, and voters have little incentive to learn the true costs of different tax systems. Ignorance about big topics like taxes is individually rational even when it’s collectively costly.

But this explanation is a little too convenient. People know property taxes fund local schools. They know sales taxes are just as real as income taxes. Often, in this newsletter, we stress that maybe people understand something that the baseline model misses. As Hobart puts it, “Tax systems are never optimal, but that’s its own kind of market efficiency at work.” So what is that efficiency?

Notice that the ranking above is in the context of growth as a proxy for things like deadweight loss, things that hold back an economy. There’s a political dimension missing in most growth models. Josh and I have a paper with Alex Salter on defense and growth. We argue defense is central to understanding economic growth. It’s not a controversial statement

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.