The King of the Emerald Pagoda

Six weeks ago I published my first book: Shattered Lands: Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia.

This came at a particularly charged moment. Tensions between India and Pakistan have once again flared, reminding us that Partition is not some closed chapter of the past. And yet, despite all the books, documentaries, and films that have covered the Partition of 1947, the story that we usually tell is somewhat incomplete.

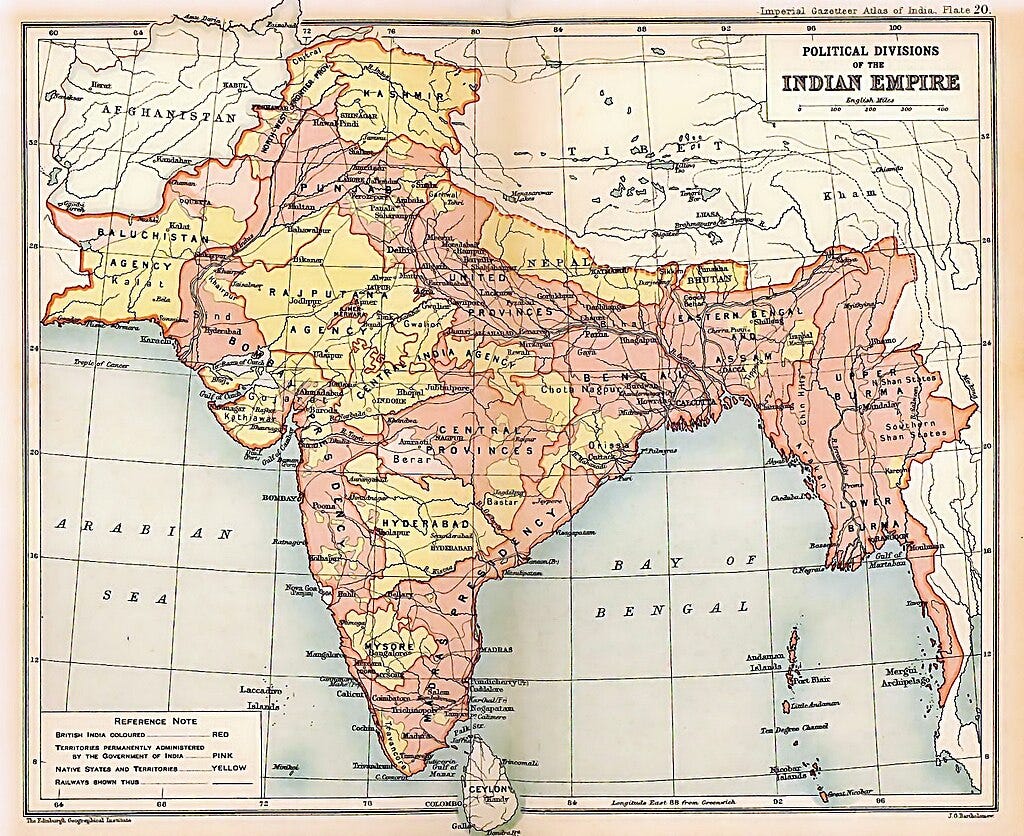

In the 1920s, the Raj was far bigger than we tend to imagine today, stretching from Yemen in the west to Burma in the east.

“Partition” was not one rupture, but a series of five imperial breakages that created twelve modern nation states.

We live in a world still shaped by its aftershocks, from the Rohingya crisis to the nuclearization of South Asian, from crackdowns in Kashmir to the origins of the Gulf War. There’s never been a more urgent time to understand how these borders were drawn, and what was broken in the process.

The First Demands for Partition

Today if you wander around Delhi or Dhaka, you wont hear many people talking about the partition of Burma in 1937. Its an almost forgotten event. Burma is always sort of there on the maps of the Raj and yet no one ever really questions it.

And yet Burma’s partition from India is arguably one of the most important events of the twentieth century, setting into motion a series of dominoes that would lead to the Bengal Famine, the Long March, the creation of Pakistan, the Rohingya Genocide, insurgencies in Northeast India and the longest ongoing civil war in the world. It’s a HUGELY important story, and one that is almost entirely forgotten.

It also has surprising lessons for post Brexit Britain. In the 1920s, Burma was arguably the economic centre of Asia. In the 1920s, the economy was booming, attracting Armenian, Tamil, Bengali, Chinese and Japanese traders, and in the 1920s more migrant workers set sail for Burma than across the Atlantic Ocean. The Burmese Dream was rapidly outpacing the American one and as one British labour official wrote shortly after the Simon Commission’s visit:

“[Rangoon] was till recently second only to New York in importance as an immigration port. It now occupies pride of place as the first immigration and emigration port of the world.

But

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.