Our Next Book: Making the Modern Laboratory

The molecular biology laboratory hasn’t changed much since the 1960s.

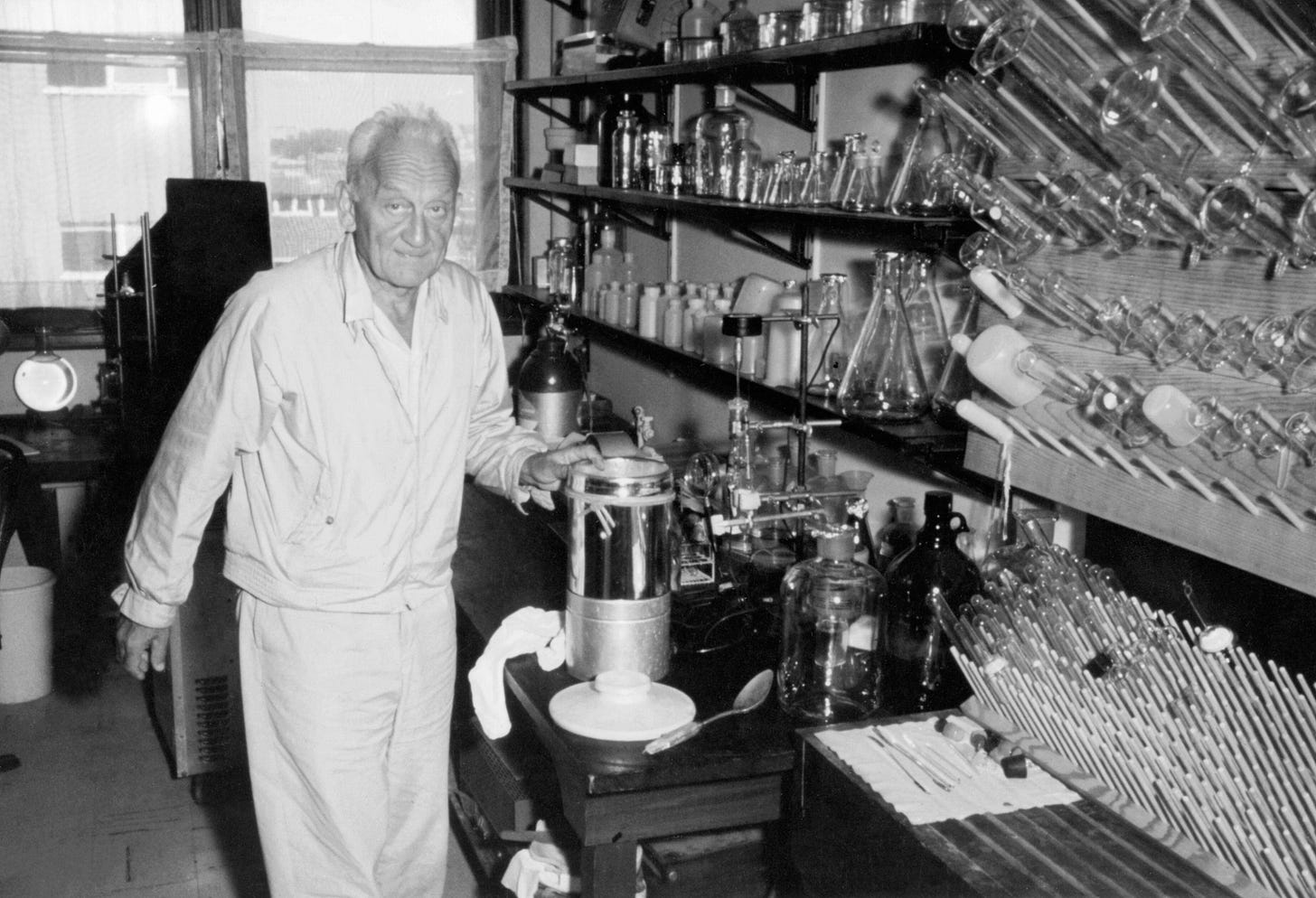

If you were to revisit photos of Howard Berg’s cramped Harvard lab, where the details of bacterial chemotaxis were first worked out, or Sydney Brenner’s Cambridge lab, where they cracked the genetic code, you’d recognize almost everything you saw.

In both, glass bottles of reagents, racks of disposable plastic tips, and half-empty boxes of parafilm wrap cluttered the benches. pH meters dangled coils of cords next to old Gilson pipettes, resting on their sides. Ice buckets held a jumble of tubes, labels fading into illegibility. A tabletop centrifuge hummed in the corner, its brushed-metal body dented from hard use. Even the smell, if you could step inside the frame, would be familiar — likely a faint mix of ethanol and agar.

People commonly point to this seeming stagnation in laboratory design while opining on how laboratories of the future ought to look. We clearly need to update our equipment, especially as AI and computational tools advance. But in many respects, the fact that our scientific devices haven’t changed much in the past 50 years also speaks to their tremendous ingenuity and versatility.

Asimov Press’s next book, Making the Modern Laboratory, aims to present the history behind the tools and methods that have helped shape modern biology research — and also to imagine what they might look like in the future.

This illustrated, coffee table-sized volume will delve into the origins of the machines, equipment, organisms, and reagents that have become familiar features of molecular biology laboratories over the last sixty years. The book will close with a set of essays that look forward, offering visions of how we could reinvent the laboratory itself. It is an intellectual companion to other books on these subjects, including The Matter Factory: A History of the Chemistry Laboratory, albeit focused on biology and more visual

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.