The Persephone Complex

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Persephone

13 min read

The article's title references the Persephone myth, and the mother-daughter relationship mirrors the Demeter-Persephone dynamic of separation, descent, and complex bonds between generations

-

Futurism

15 min read

The mother's dissertation studied the Futurists, and the article engages with Futurist aesthetics and their relationship to power, fascism, and the deliberate embrace of severity over sentimentality

-

Albert Speer

11 min read

The mother is compared to 'the Albert Speer of neoliberal imperialism' - understanding Speer's role as Hitler's architect who aestheticized Nazi power illuminates the article's central themes about art serving power

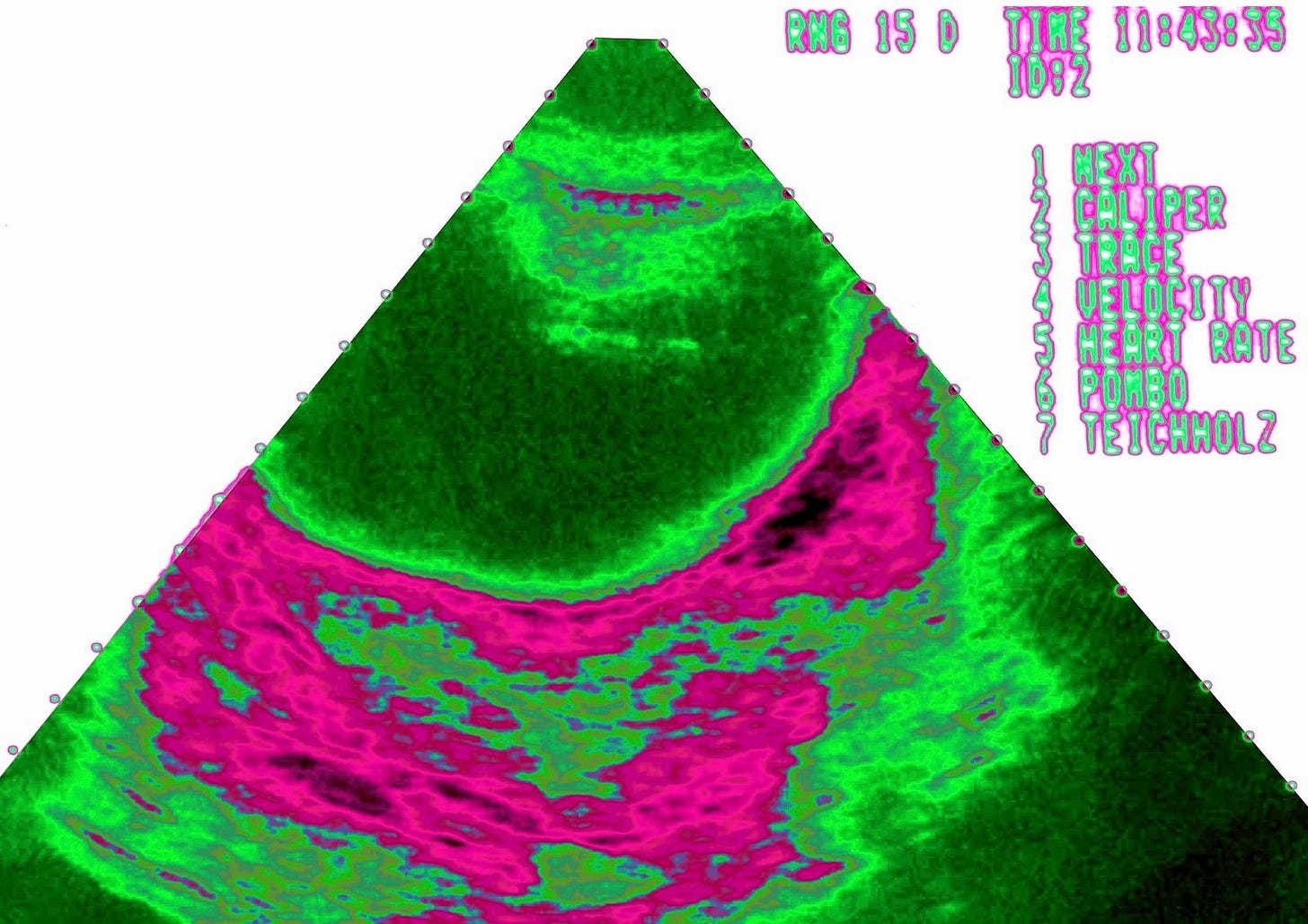

My mother wasn’t able to have children. She’d been diagnosed with a severely “bicornuate” uterus. Its deep top cleft would not permit a fetus’ implantation or habitation. This congenital irregularity has been called both “horned” and “heart-shaped” in the clinical literature, depending, I assume, on the observer’s temperament. My mother, pleasantly surprised at my safe arrival after a brief and almost anonymous tryst on an Italian research trip she’d taken in graduate school, inclined toward the heart. “It’s a symbol of how much I loved you from the beginning,” she would tell me when I was a child. She liked to show me her old ultrasounds on the computer.

She’d gone to Italy to study the Futurists for a chapter in her controversial doctoral dissertation, Art as Power: A Defense. “I finished in 2002, the year after my daughter was born,” she told an interviewer about two decades after that. “It was a good year to make an argument of that kind, and to take it from academe to the private sector. Security was booming in those years.” She added, “Later, of course, you’d get run out of academia for saying what I said. The argument was perfectly obvious, however. What gives it a certain cachet is only that it’s become forbidden. When you make an obvious idea forbidden, you give it an almost erotic glow.” I’m watching that interview now, your grandmother’s straight silver hair radiating against a black backdrop. Soon I’ll watch my other favorite video again, the one where she’s picketed as she tries to give a speech on a college campus, just smiling silently, barely even blinking, as the chants denouncing her as a torturer and murderer get more and more wild until police drag the protesters out. She explained her obvious, forbidden idea in the dissertation’s first chapter, which I quote here (I have the document open as I write you this letter):

Artists and humanists have grown very comfortable over the last half-century with the idea that the aesthetic serves power, makes power appear attractive or legitimate or original, functions the way Marx described religion: as a flower on the chain of oppression. Our comfort, however, is illusory, a tough-minded posture concealing a sentimental evasion. This insight about art has led to an endless inquisition of art, though “inquisition” puts it too strongly. We have actually pled

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.