Secular Messianism

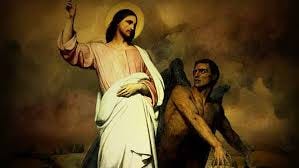

Messianism is one of the most dangerous ideas in the history of mankind. Not only is the most famous example of messianic movement predicated on the messiah in question being an ironic inversion on the expected soteriological quality, but the helplessness of the idea-thinker in relation to the realisation of messianic promise makes for a strange jitteriness, an uncomfortable “otherness” to the object of desire—they are in constant threat of becoming the agent of Infinite Resignation1, handing off their responsibility for their salvation to some “Big Other”, the exercising of free will to surrender one’s capacity to live life.

In the moment of the messianic recallibration of reality, the slate is cleaned of its impurities and the totality of existence is reanalysed in the context of this new “breaking through” that takes whatever came before, reorganises without destroying it, and presents something new to the world. The constant danger sits on the periphery: the cry for a messiah imposes the craving for power of the individual onto the perfect image in order to justify any and all acts towards any and all ends.2

When this object becomes yoked to the individual as a mere aesthetic object, an “other” that pulls him from his position and tears up the foundations of his world, it becomes a desire that breaks through all walls and runs roughshod through all enemies that stand between the convert and his salvific object: the Maoist struggler, the liberal resister, the Islamist terrorist—all of them are captured by the basic logic of secularity. If not for the particular, world-inverting presence of a messiah, there would be little to stop the Christian call to opposition against the world from descending into an anthropocentric, domineering philosophy that sharpens ploughshares into swords and salivates at the thought of “an eye for an eye”. The very mode for us to recognise the good becomes inverted by human ingenuity—Vordenken3 allows for the very good to become a temptation4.

Labadie against Marxist “Science”

Laurence Labadie had little time for Christianity in the same way that slugs have little time for salt or that Richard Dawkins has time for writing philosophy worth reading. As was appropriate for a thinker swept up in the “demand of the times” in

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.