Has Music Gotten More Political? A Statistical Analysis

Intro: Not Ready to Make Nice

For a short time in the early 2000s, the country band formerly known as The Dixie Chicks found themselves at the center of pop culture for being “too political.”

In 2003, just days before the U.S. invaded Iraq, Dixie Chicks lead singer Natalie Maines told a London audience that she was “ashamed the President of the United States is from Texas.” The remark spawned massive backlash, especially from the Chicks’ core country fanbase. Radio stations banned their songs, and Fox News labeled the group “unpatriotic,” leading the band’s airplay to drop to 20% of what it had been before the controversy.

Three years later, The Dixie Chicks returned with a Grammy-winning album, headlined by the defiant lead single “Not Ready to Make Nice.” The group’s comeback was hailed as a “triumph,” though their resurgence was short-lived. Despite their Grammy success, The Dixie Chicks were blocked from country radioplay, and their efforts to cultivate a progressive pop/folk crossover audience—if such a base ever existed—failed to generate the same level of visibility. In 2020, nearly two decades removed from their anti-Bush comments, the band dropped “Dixie” from its name in response to racial justice protests across the U.S.

The Chicks may be the most prominent example of a music act “cancelled” for wading into America’s totally-awesome-and-not-at-all-exhausting Culture Wars. But was the politicization of their music—and the backlash it sparked—an anomaly? Or was the anti-Bush firestorm a sign of things to come? Has music become more socially conscious in the years between The Dixie Chicks’ rise and their eventual rebrand as The Chicks?

So today, we’ll explore whether popular music has grown “more political,” what drives the politicization of pop culture, and how lyrical content differs for Billboard-charting songs.

Has Music Gotten “More Political”?

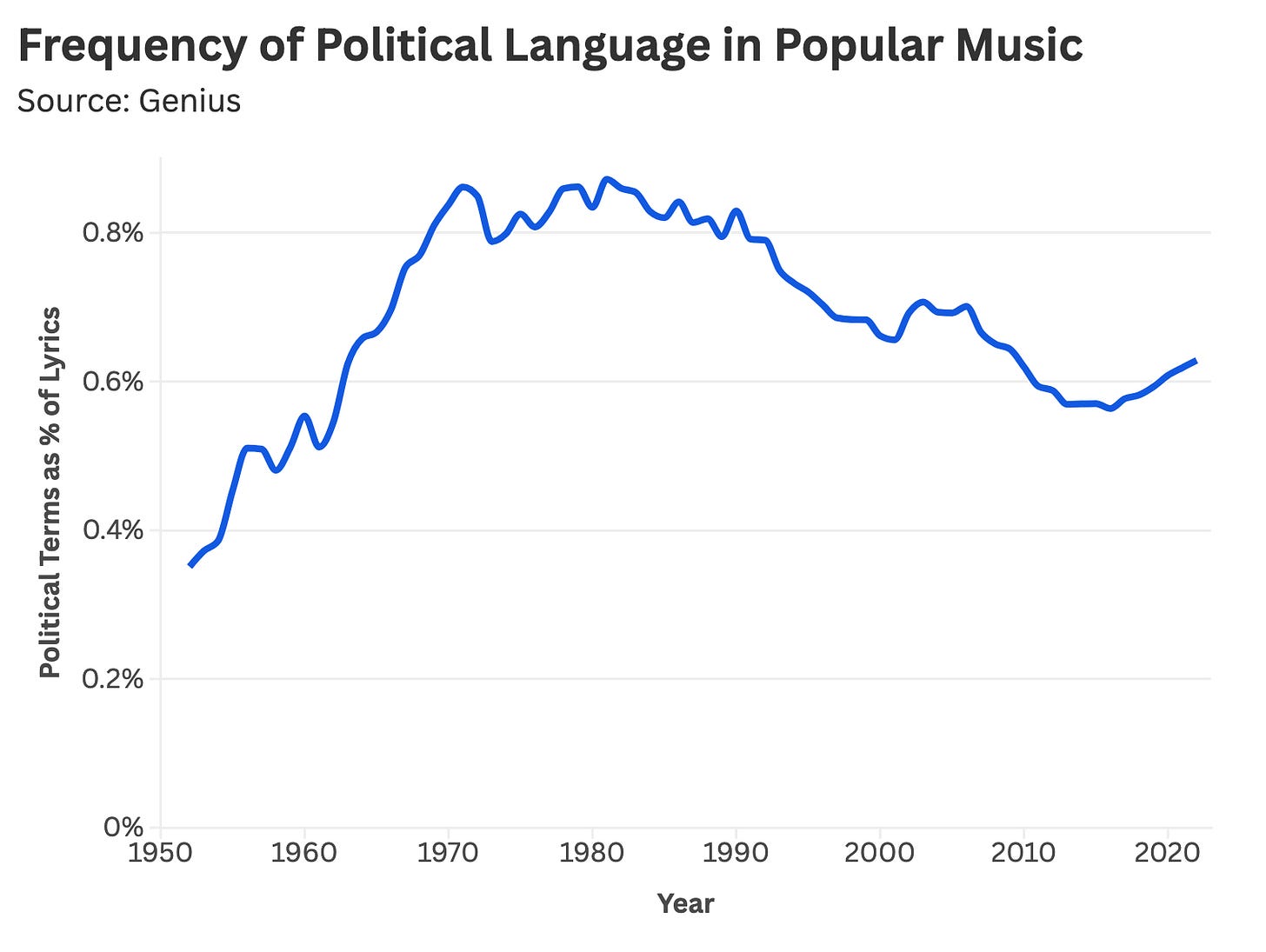

We’ll use textual frequency to measure a song’s political content. For each track, we’ll count the number of politically oriented terms, such as “justice,” “revolution,” and “equality,” and divide this figure by the total number of unique words in that song. The resulting ratio is a song’s political density.

When we average our political density figure for all major record label releases since the 1950s, we find that lyric politicization peaked in the late 1970s, then steadily declined for decades before a modest resurgence in the late 2010s.

Given the sheer pervasiveness of

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.