Even meritocratic systems aren’t fair

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery

9 min read

The article discusses the Armed Forces Qualifying Test and how test scores determine military career assignments. The ASVAB is the actual test battery that includes the AFQT, and understanding its structure, history, and how it's used for military occupational specialty assignments would give readers crucial context for the study's findings.

-

Regression discontinuity design

11 min read

The article mentions 'regression discontinuity studies' of exam schools in New York and Boston as evidence for its argument. Most readers won't understand this statistical methodology, and knowing how RDD works helps evaluate the strength of the evidence presented about test thresholds and their arbitrary nature.

-

Peter principle

13 min read

The article's core finding - that overqualified workers are demotivated but still promoted while underqualified workers are motivated but less promotable - directly relates to theories about competence and organizational hierarchy. The Peter Principle offers a complementary lens for understanding how meritocratic systems can produce suboptimal outcomes.

The amount of money you’re able to earn at age 40 is in part a function of the on-the-job learning you’ve done earlier in your career. But the opportunities you got to do that learning earlier in life are in part a function of underlying competency, which continues to be relevant to your age-40 earnings.

These factors are particularly hard to untangle because, even though there are definitely hierarchies in the American education system, they tend to be a bit vague and informal — there’s no official rank-ordering of colleges or other schools.

The way the Air Force slots enlisted airmen into various career tracks, based in part on test scores, is an interesting exception to that vagueness and informality.

What makes the slotting particularly interesting is that it’s not entirely based on test scores, because the Air Force doesn’t exist to make sure everyone is treated fairly — it exists to perform a specific mission. And in order to perform that mission, it needs a specific quantity of people in specific jobs. If there’s an unusually large number of vacancies in a specific occupation at the time you happen to sign up, that increases your odds of being assigned to it, even if in a different year your score might have been just a bit too high or just a bit too low for that assignment. The average quality of the new enlistees also varies somewhat from year to year. So a score that might have been above average in 2019 when the national labor market was strong might have been below average in the weak labor market of 2010.

This allowed Julie Berry Cullen, Gordon B. Dahl, and Richard De Thorpe to conduct an interesting study where they look at what happens to people who get assigned to jobs for which they have unusually high or unusually low test scores.

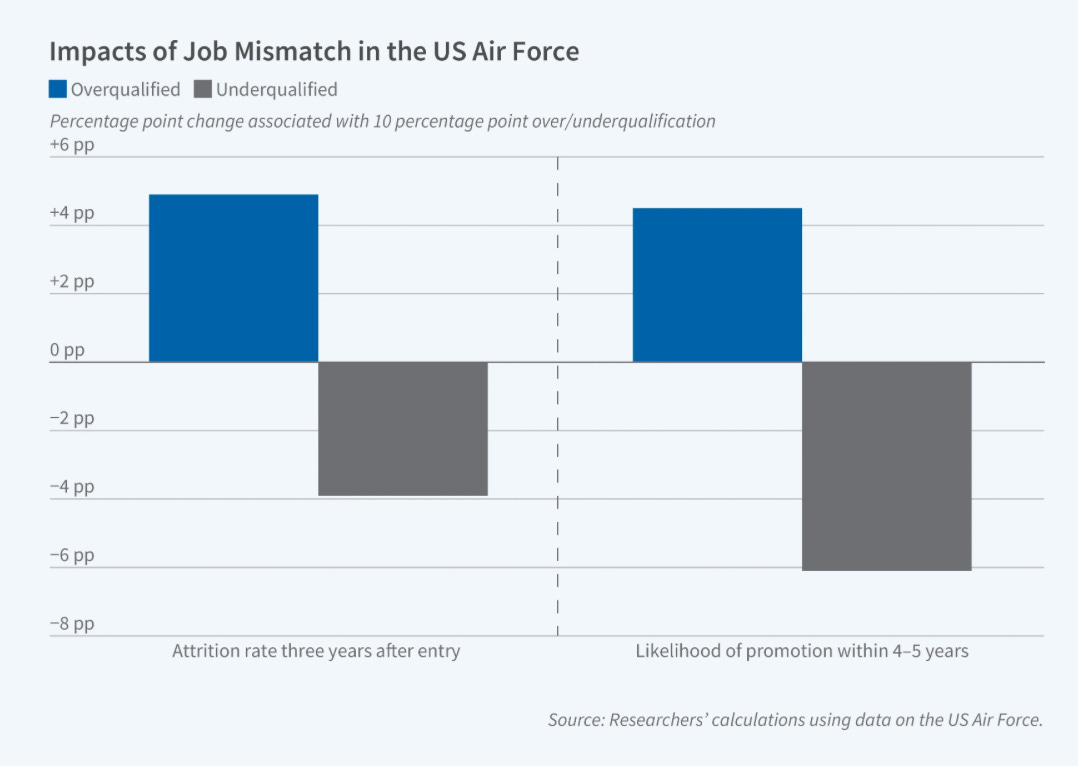

What they find is that overqualified applicants are unusually likely to quit (and underqualified applicants unusually unlikely to quit), but they’re also more likely to be promoted (again the reverse is true for the underqualified).

Beyond attrition, the people who are overqualified for their jobs display a range of problems. They manifest more behavioral issues, they get worse performance evaluations, and they do worse on general knowledge tests about the military. They seem, in other words, to

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.