Leaving the IPCC and UNFCCC is Bad for the United States

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Kyoto Protocol

12 min read

The article mentions the Kyoto Protocol as the specific treaty being negotiated when the Byrd-Hagel resolution was passed. Understanding what the Protocol actually required, which countries ratified it, and how it functioned without US participation illuminates the concrete policy stakes the article discusses regarding UNFCCC withdrawal.

-

Treaty Clause

13 min read

The article raises the unresolved constitutional question of whether a president can unilaterally withdraw from treaties ratified by the Senate, citing the Carter-Taiwan case. This Wikipedia article explains the constitutional framework for treaty-making and termination powers, providing crucial legal context for understanding why UNFCCC withdrawal authority remains contested.

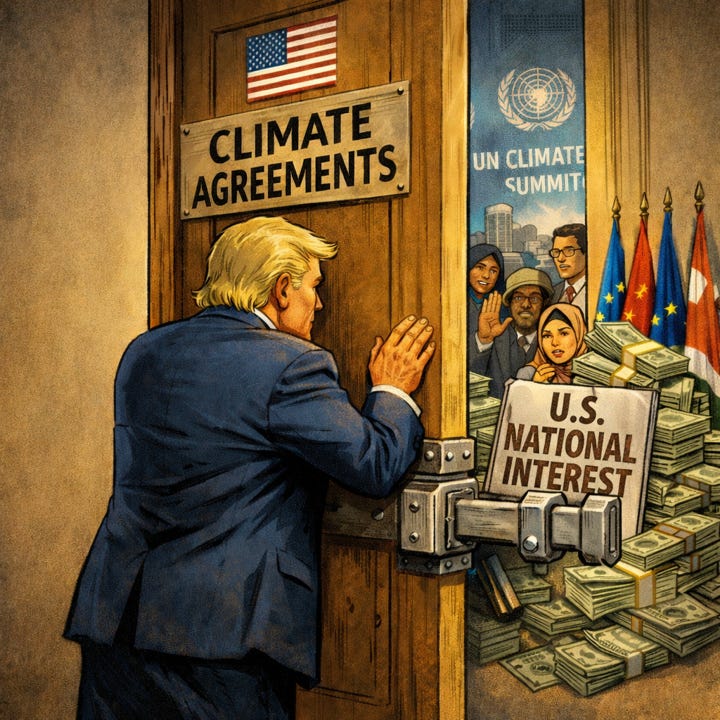

Yesterday, the Trump administration announced via executive order that the United States was withdrawing from 66 international organizations, of which 31 fall under the United Nations (UN).1 Among these organizations are the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).2

Today, I explain a bit about these organizations and why it is contrary to the interests of the U.S. — and also, perhaps surprisingly, the stated interests of the Trump administration — to formally withdraw from each.

Before proceeding, let me acknowledge that there are surely considerable propaganda benefits to the Trump administration of announcing this rejection of multilateralism. Globalists! Woke! Hoax! Similarly, the embrace of these organizations by the Biden administration was also arguably more about propaganda than policy. Existential threat! Threat multiplier! Follow the science!3

On both sides, strong partisans will readily cheerlead along with the rhetoric. However, beyond the news cycle and team sport, there are real world policies with real world impact, including impact on the fortunes of normal Americans.

Today’s post addresses three points:

The U.S. government — meaning the President and Congress, and both parties when in control of each — has for more than 30 years rejected the UNFCCC as little more than a talking shop, with no real policy teeth. Even so it matters;

The U.S. helped to create the IPCC in the 1980s to push back against climate activism perceived to contrary to U.S. interests, notably that based on flawed or exaggerated scientific claims. A robust IPCC serves U.S. interests;

U.S. engagement in multilateral organizations is a source of soft power that has proven meaningful to advance U.S. interests — obviously in economics and defense, but also in 2026 in science as well.

Let’s take a closer look at each.

U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change

The Trump administration’s withdrawal EO may not actually withdraw the U.S. from the UNFCCC.

It states:

For United Nations entities, withdrawal means ceasing participation in or funding to those entities to the extent permitted by law.

The UNFCCC is technically a “non-self-executing” international agreement. That means that as a signatory, the U.S. has no formal obligations other than those that might come in the aftermath of becoming a signatory, i.e., that Congress and the President together decide to implement in law.

The Congressional Research Service explains:

...In

This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.