When facing a complicated problem, don't try to solve it, try to understand it

I wrote this essay with Johanna Karlsson, so it is a collaboration but I narrate. /Henrik

Every problem cries in its own language

Go like a blood hound where the truth has trampled

—Tomas Tranströmer, “About History”

1.

Like most people, I was really bad at making decisions when I was 25. If I was confronted with a complicated problem, like figuring out what to do with my life, I would pick a solution on a whim, more or less, or, if that was too hard, I would straightforwardly just ignore the problem. This made my life feel less than good at times. But then something fell in place.

Or no, it wasn’t a specific moment like that. It was more the cumulative effect of spending 36 years trying things and failing and learning a little bit here and there, and—mostly over the last four and a half years—having a few conceptual breakthroughs. Most of the insights, interestingly, came after my wife Johanna decided to turn the derelict grounds around our house into a garden. Ambitious gardening, as it turns out, is a good way to get better at dealing with messy problems.

Let me tell you about that and the core thing I learned.

So, in 2021, when our oldest daughter Maud was four and Johanna was pregnant with Rebecka, we bought an old farm on an island in the Baltic Sea. We were able to get it cheaply because there was a glorious total of one single room that could be heated in winter. Also, a large swarm of false spirea shrubs was pushing right up against the house (they were even growing inside the walls, we later discovered—ghostly white trees with leaves like paper; don’t even get me started).

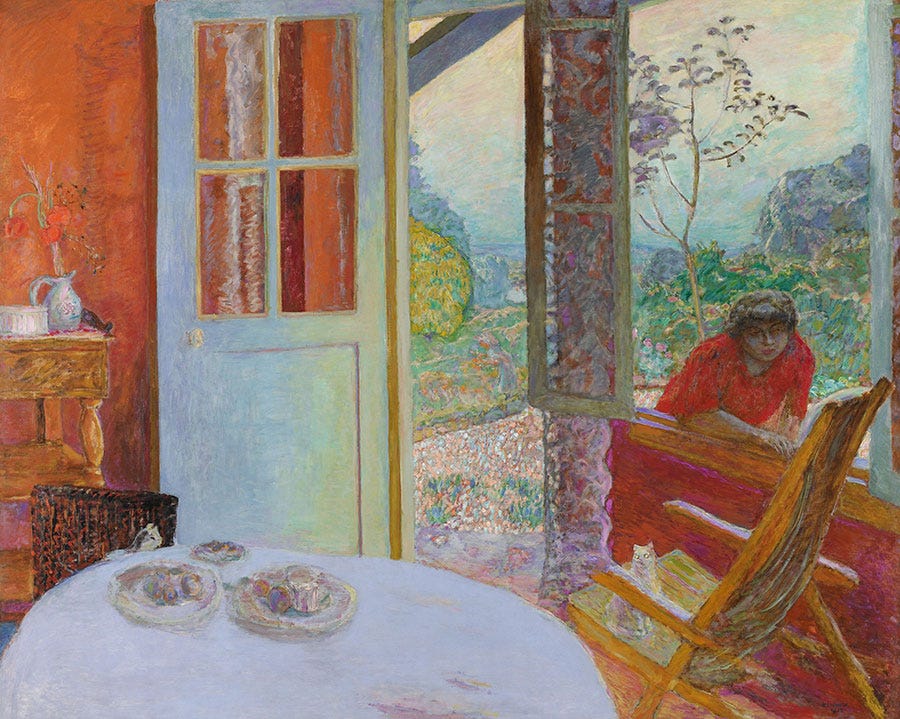

Anyway, it was while removing the tennis-court-sized section of shrubs closest to the house that Johanna got the feeling that this place, despite its appearances, was actually meant to be a great garden. Under the overgrowth, we uncovered stone walls and beautiful differences in elevation with views into the forest, where evening light striped the ground with the shadows of maples and oaks. It was like when you get half an idea for an essay and just know that this thing could turn into something deep and moving if you pour everything you have into it.

The more Johanna thought about it, the more she felt like she

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.