VERSIONS OF ABJECT: UGLY, CREEPY, DISGUSTING (PART TWO)

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Julia Kristeva

13 min read

The entire article is a deep engagement with Kristeva's theory of abjection from 'Powers of Horror'. Understanding her intellectual biography, psychoanalytic framework, and philosophical contributions is essential context for readers unfamiliar with her work.

-

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

17 min read

The article extensively analyzes Céline's literary confrontation with the abject and his troubling turn to fascism and anti-Semitism. His complex legacy as both a literary innovator and Nazi collaborator is central to understanding Kristeva's argument.

-

Abjection

15 min read

The concept of abjection as developed in psychoanalytic theory, particularly the boundary-dissolving horror between subject and object, is the core theoretical framework of this essay. The Wikipedia article covers the philosophical and psychoanalytic dimensions readers need.

Welcome to the desert of the real!

If you desire the comfort of neat conclusions, you are lost in this space. Here, we indulge in the unsettling, the excessive, the paradoxes that define our existence.

Below, the second part of a longer essay. Please go back to part one if haven’t that already.

Traversing Abjection

Up to now, we have been dealing with the main modes of avoiding the abject. There are, however, two privileged ways of traversing abjection—of going through it and purifying ourselves of it: religion and art (poetic catharsis). “The various means of purifying the abject—the various catharses—make up the history of religions and end up with that catharsis par excellence called art, both on the far and near side of religion” (17).

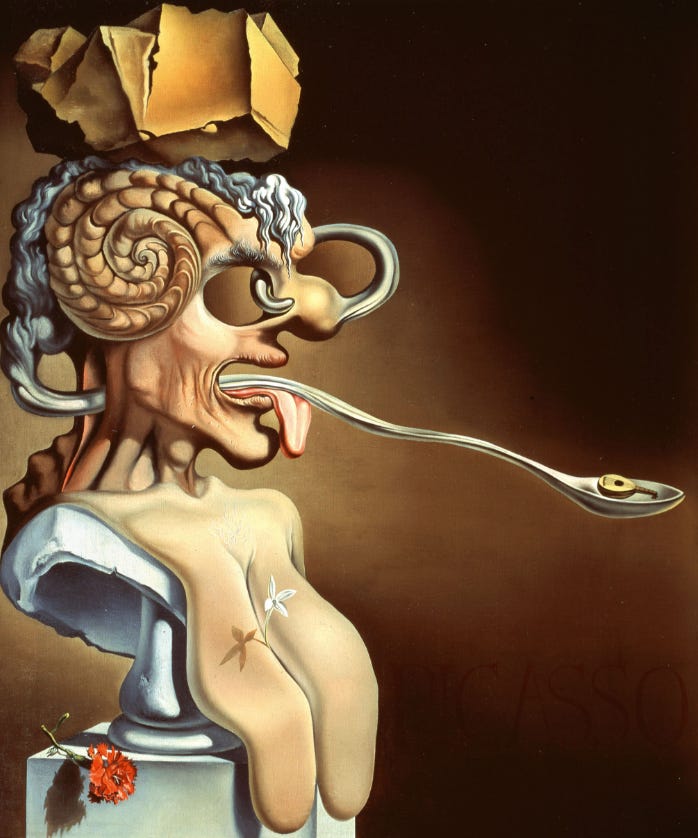

The whole of modern literature and art, from Artaud to Céline, from Kandinsky to Rothko, confronts and tries to sublimate the abject. Following Rilke’s famous formula, “beauty is the last curtain before the horrible,” it weaves a screen that renders the abject not only tolerable but even pleasurable: “On close inspection, all literature is probably a version of the apocalypse that seems to me rooted, no matter what its socio-historical conditions might be, on the fragile border—borderline cases—where identities (subject/object, etc.) do not exist or only barely so: double, fuzzy, heterogeneous, animal, metamorphosed, altered, abject” (207).

In a detailed analysis, Kristeva presents the work of Céline as a long and tortuous confrontation with the abjectal dimension. This is what “the long voyage to the bottom of the night” (the title of his masterpiece) alludes to—the night of the abject, which suspends not only reason but the universe of meaning as such, not only at the level of content (describing extreme states of dissolution) but also at the level of form (fragmented syntax, etc.), as if some pre-linguistic rhythm—“the ‘entirely other’ of significance”—were invading and undermining language:

It is as if Celine’s scription could only be justified to the extent extent that it confronted the “entirely other” of signifiance; as if it could only be by having this “entirely other” exist as such, in order to draw back from it but also in order to go to it as to a fountainhead; as if it could be born only through such a confrontation recalling the religions of defilement, abomination, and sin.

Céline carefully walks on the edge of this vortex of ecstatic

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.