Friendship, an Invention of Late Capitalism

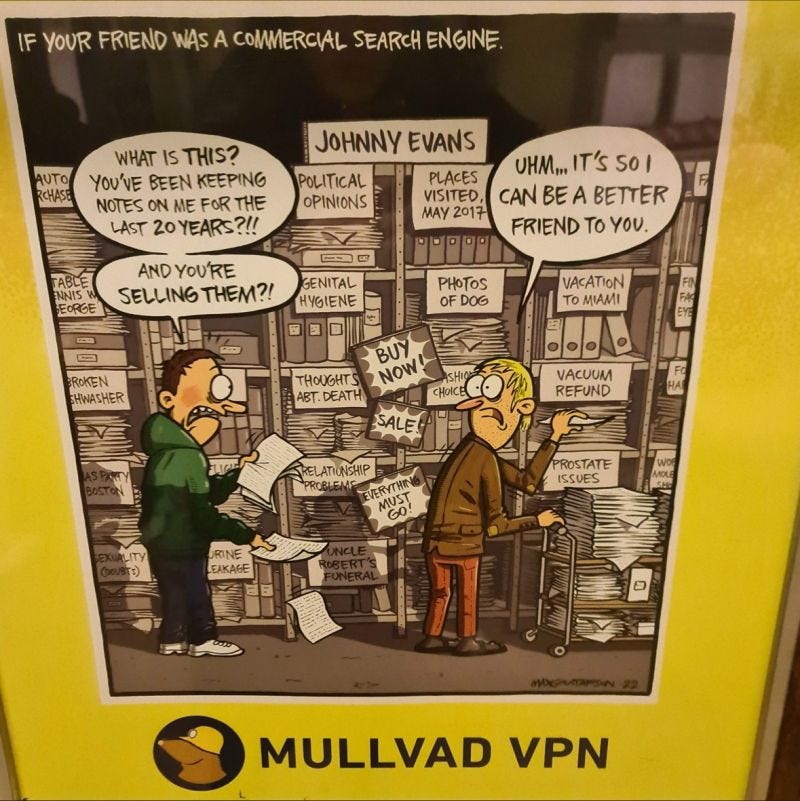

One of the greatest achievements of new media structures (whether it is procedural film franchises, TikTok, live streaming, algorithm-designed music, YouTube, or ‘independent’ news outlets) is the method in which they retroactively reformat whatever preceded them. Or as Guy Debord put it, new media ideology installs a new temporality, reframes itself not as a violently ‘new’ or irreducible formation, but rather imperceptibly imposes itself as the natural outcome of historical development. The transgression of new media is perplexing enough to merge with, and reconstitute, what previously appeared neutral, or outside the zone of ideology. The seemingly innocent meaning of friendship is just such an example. When I was on the London Underground, I saw the following advert for Mullvad VPN:

If a friend behaved as a commercial search engine, storing and selling off everything they knew about us, we would rightly be very concerned. And yet the real meaning of this comparison between friendship and the internet is more perplexing than it initially appears. A strange double-obfuscation characterises this image. On the one hand, it uses a disorienting form of comparison between incomparable categories which has only become possible with the increased ‘mediatisation’ of the social and private sphere.

This forced homogenisation – the conceptual equation of otherwise incompatible or qualitatively irreconcilable objects – is central to the structures of postmodern exchange which Fredric Jameson diagnosed. Whether it is through the play of film (and its migration into online video consumption) on the position of the observer himself; the transgression in postmodern architecture of the boundaries between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’, where both categories become untenable, thereby defeating the original ‘sheltering’ purpose of housing itself; or the making-public of private life through the economically manufactured image of the inner self in late capitalist appropriation – the new media empire is not self-contained. It operates instead by a perpetual displacement and inversion of limits, not by the conjunction of opposites, but by eradicating the basic notion of opposites in a homogenous entanglement of distinct forms.

We saw exactly this in one of Michel Haneke’s great postmodern treatises, The Seventh Continent (1989), a more faithful representation of the self-destructive logic of late corporatised family life than more popular films such as Falling Down (1993) or Office Space (1999). The film displays a series of anonymised fragments or snapshots (in which faces are rarely revealed) of a suburban family and the labour of

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.