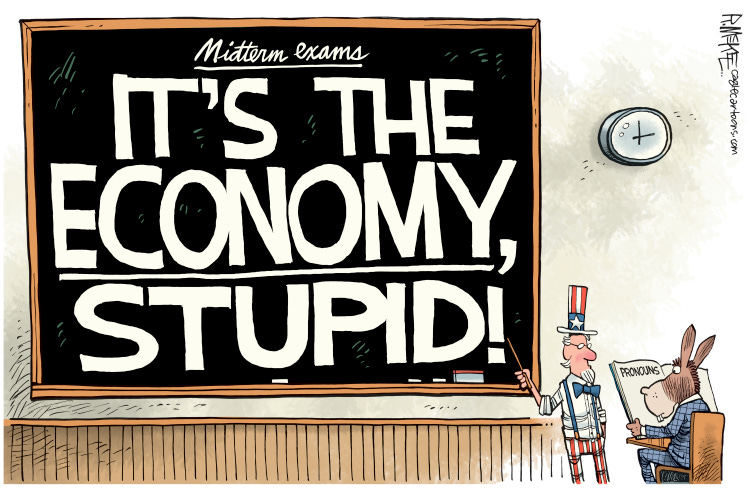

Contextualizing the 2024 Election: It's the (Knowledge) Economy, Stupid

Note: I published the essay that follows about a year ago. It draws heavily on themes from both my newly released book (We Have Never Been Woke) and my next book (details coming soon). As you’ll see, the essay nicely explains the 2024 electoral results.1

Rather than viewing the gender divide, the ethnic shifts, the education divide, etc. as separate phenomena, it’s more insightful to understand them as facets of a more fundamental schism in American society. And many other societies worldwide. Namely: a divide between “symbolic capitalists” and those who feel unrepresented in our social order.2

I fear that, as happened in 2016, rather than really taking the points of this essay to heart, the impulse in many symbolic capitalists spaces will be to try to pathologize *the voters* rather than the Democratic party, its candidates, its messaging, or its platform and priorities. So I’m hoping to inoculate readers against those types of asinine takes by presenting an alternative — and analytically powerful —way of understanding what’s going on.

For editors/ journalists interested in essays or interviews about any of this stuff, hit me up ASAP. My bandwidth is tight because of the book tour, but I'll make time for the right pitch.

The biggest divide in American politics at present is not along the lines of socioeconomic status (SES), nor educational attainment, nor type (urban, suburban, small town, rural), nor gender — nor is it tied to “identity politics,” “populism,” or the “crisis of expertise” — although these factors all serve as important proxies for the distinction that matters most. The key schism that lies at the heart of dysfunction within the Democratic Party and the U.S. political system more broadly seems to be between professionals associated with ‘knowledge economy’ industries and those who feel themselves to be the ‘losers’ in the knowledge economy – including growing numbers of working class and non-white voters.

Two decades ago, sociologists Manza and Brooks observed, “professionals have moved from being the most Republican class in the 1950s, to the second most Democratic class by the late 1980s and the most Democratic class in 1996.” The consolidation they noted at the turn of the century is even more pronounced today. And as these professionals have been consolidated into the Democratic Party, they’ve grown increasingly progressive, particularly on

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.