When is it better to think without words?

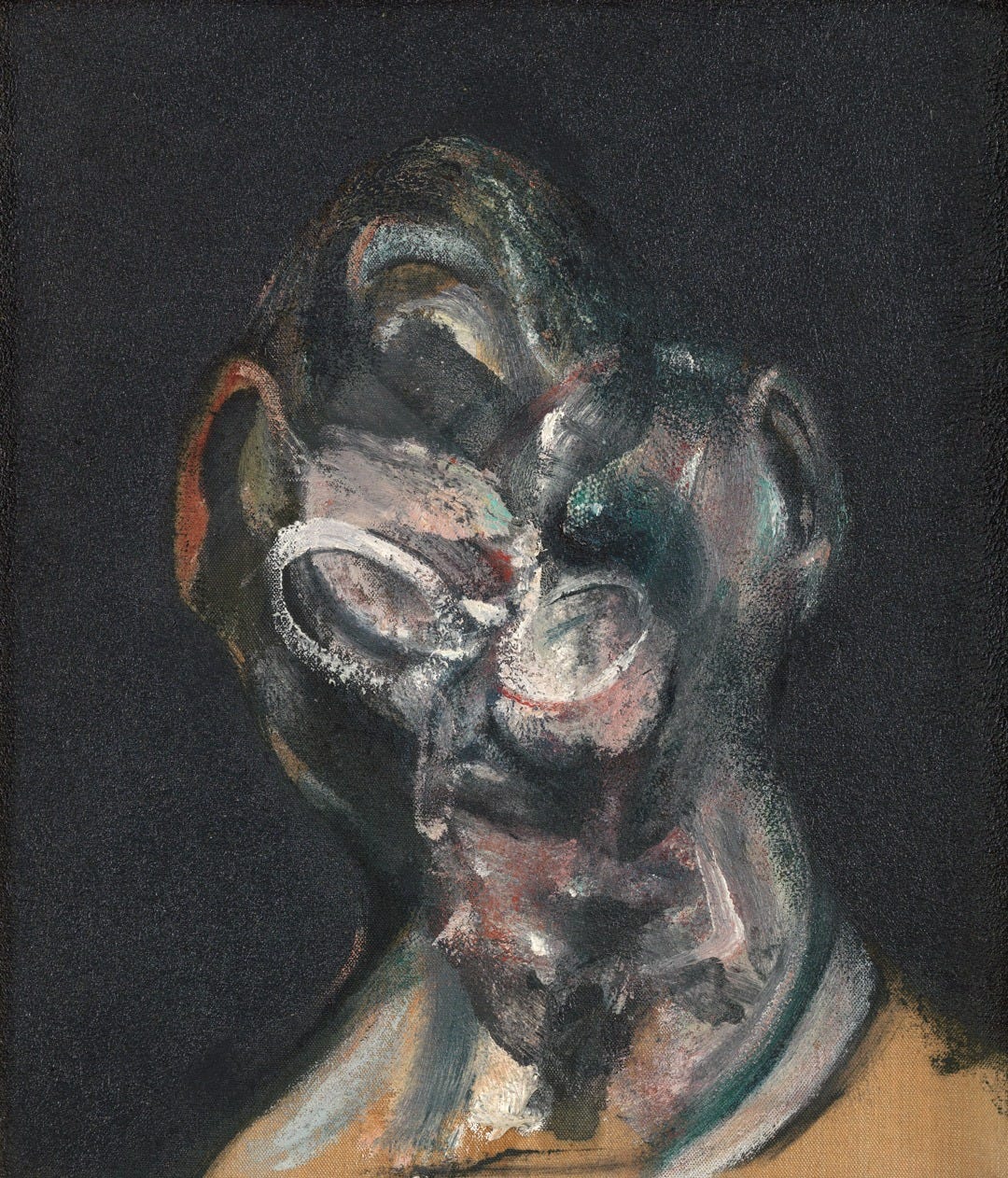

Portrait of a Man with Glasses I, Francis Bacon, 1963

This essay can be read as a complement to last year’s “How to think in writing.”

Thoughts die the moment they are embodied in words.

—Schopenhauer

1.

In the 1940s, when the French mathematician Jacques Hadamard asked good mathematicians how they came up with solutions to hard problems, they nearly universally answered that they didn’t think in words; neither did they think in images or equations. Rather, what passed through the mathematicians as they struggled with problems were such things as vibrations in their hands, nonsense words in their ears, or blurry shapes in their heads.1

Hadamard, who had the same types of experiences, wrote in The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field that this mode of thinking was distinct from daydreaming, and that most people, though they often think wordlessly, have never experienced the kind of processing that the mathematicians did.

When I read this, in December 2024, all sorts of questions arose in me. First of all, what does it even mean? Do they not think in words and equations at all? And secondly, how do I square this with my personal experience, which is that whenever I write what I think about a subject, it always turns out that my thoughts do not hold up on paper? No matter how confident I am in my thoughts, they reveal themselves on the page as little but logical holes, contradictions, and non sequiturs.

I recognize myself when Paul Graham writes:

The reason I’ve spent so long establishing [that writing helps you refine your thinking] is that it leads to another [point] that many people will find shocking. If writing down your ideas always makes them more precise and more complete, then no one who hasn’t written about a topic has fully formed ideas about it. And someone who never writes has no fully formed ideas about anything nontrivial.

How come Hadamard’s colleagues are able to have productive thoughts, working in their heads, without words, sometimes, for days on end?

Tense subconscious processing

Hadamard’s book is most famous for its detailed discussion of what Henri Poincaré called the “sudden illumination”—the moment when the solution to a problem emerges “in the shower” unexpectedly after a long period of unconscious incubation.

The hypothesis here is that if you work hard on a problem, you soak

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.