Monopoly Round-Up: A Gunboat Oligarchy Goes After Venezuelan Oil

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Andrew Mellon

17 min read

The article extensively discusses Mellon's role as Treasury Secretary and his use of government power to secure oil concessions for Gulf Oil. Understanding his full biography, political influence, and the Patman impeachment attempt provides crucial historical context for the parallels drawn to current events.

-

Wright Patman

13 min read

Patman's impeachment campaign against Mellon is a central historical parallel in the article. His decades-long career fighting monopolies and Wall Street power offers deeper context for understanding anti-monopoly movements and their political challenges.

-

Banana Wars

14 min read

The article references 'gunboat diplomacy' and U.S. interventions in Latin America during the early 20th century. The Banana Wars represent the broader pattern of U.S. military interventions to protect corporate interests in the Caribbean and Central America that the article argues is being revived.

Ok, so I was going to do a year end review and predictions issue today for the anti-monopoly movement, but yesterday, the U.S. engaged in regime change in Venezuela. At the end of this post, I’ll have the usual monopoly round-up, with lots of news. But we’ll start with the situation in Venezuela, about which Wall Street is very excited.

The best way to understand what just happened is to start with history. Because while Trump is unusually explicit about his rationalization for seizing control over a resource-rich territory, U.S. domination of the oil reserves of South America is not new. And neither is the fusion of corporate and state interest.

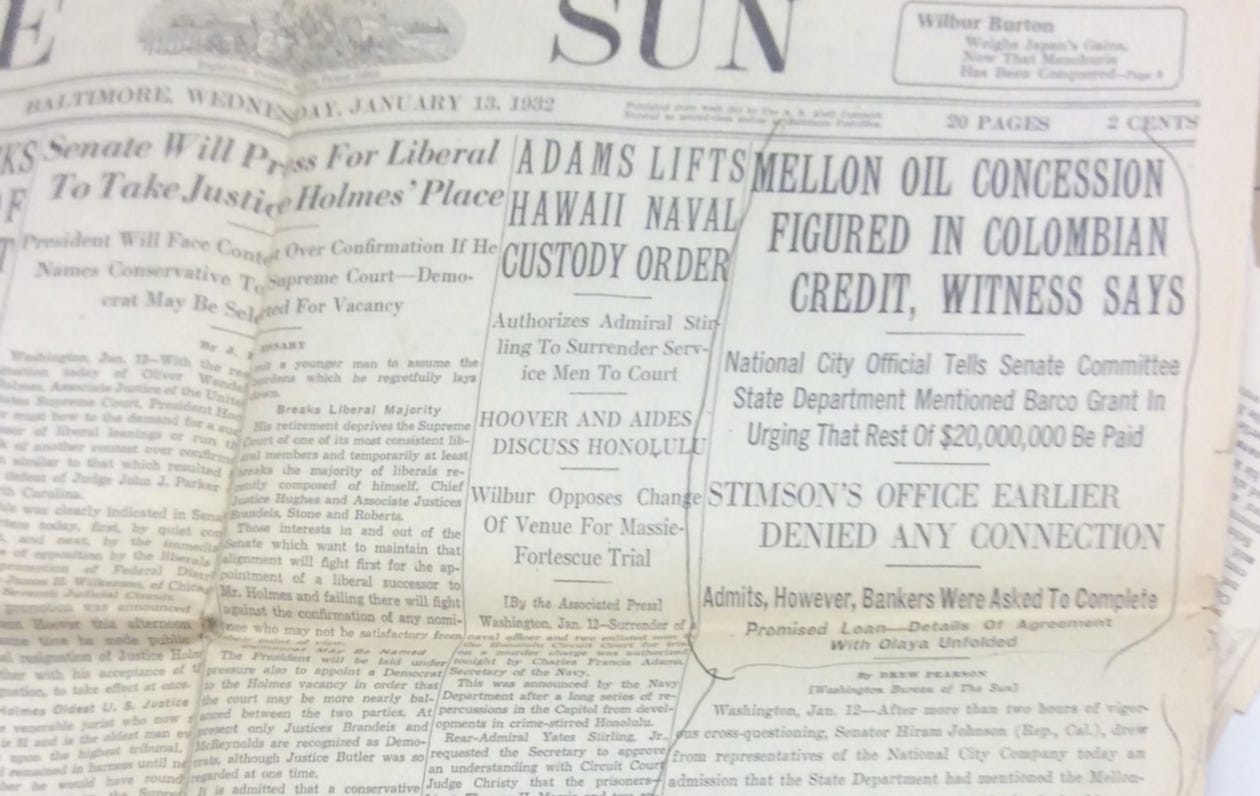

Ninety five years ago, in 1931, Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, who owned Gulf Oil (now Chevron), forced the President of Colombia to give his company the Barco oil concession, which borders Venezuela. How? Well Wall Street banks and the U.S. government threatened to withhold vitally needed bank loans if Colombia did not cede the franchise.

The parallels to the situation today are there. When Mellon seized these reserves, in partnership with JP Morgan banking interests, gunboat diplomacy was the norm. In the prior two decades, the U.S. had finished brutally putting down a resistance movement in the Philippines, and had become the global economic and political power after a gruesome world war. Woodrow Wilson had tried to establish a global rules-based order, which the GOP in the 1920s sabotaged.

At the time, Democrats were incompetent and split, as it was an era of deep reverence for the wealthy and bitter culture warring over race and alcohol. For instance, the head of the DNC in the late 1920s, a Dupont executive named John J. Raskob, published a pamphlet titled “Everybody Ought to Be Rich” encouraging Americans to borrow money to invest in the stock market.

Just as there is increasing support for cynical and nihilistic figures today, many in the 1920s felt warmly towards Mellon, Mussolini, and authoritarianism in general. U.S. Steel chairman Judge Elbert Gary encouraged Americans to “learn something by the movement which has taken place in Italy,” while progressive and New Republic founder Herbert Croly called Mussolini as substituting “purposive behavior for drifting and visions of a great future for collective pettiness and discouragement.” Gunboat diplomacy fit in well.

To be sure, there were opponents of Mellon and the super-wealthy, like New York Governor Franklin Delano

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.