Inside the Affordability Crisis

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Panic of 1907

13 min read

The article mentions discussing 'the 1907 crisis and the rise of non-banks' on a podcast. This financial panic led to the creation of the Federal Reserve and has parallels to modern concerns about non-bank financial institutions and systemic risk.

-

Government-sponsored enterprise

10 min read

The article discusses Fannie Mae as a mortgage guarantor. Understanding the unique structure of GSEs—quasi-governmental entities that back most US mortgages—provides essential context for why the American mortgage market functions so differently from other countries.

-

Mortgage-backed security

18 min read

The article references securitization requirements and the apparatus ensuring mortgage liquidity. MBS are the financial instruments that transformed mortgages from local bank products into globally traded securities, directly causing the 2008 crisis and shaping current regulations.

Happy Friday. I was back on the Macro Hive podcast this week, talking to host Bilal Hafeez about a range of things we’ve addressed in the newsletter over the past few months: AI bubbles past and present, the 1907 crisis and the rise of non-banks, private credit risks, fraud cycles, Jane Street’s technological edge, blockchain’s slow creep into banking, and what AI means for entry-level finance jobs. We also touched on two books I’m reading: 1929 and The Land Trap. The episode is available on all the usual platforms.

I’m also hosting a webinar on December 4th about the private credit marketplace, sponsored by AlphaSense. Details further down, or you can sign up here. For now, though, back to the newsletter...

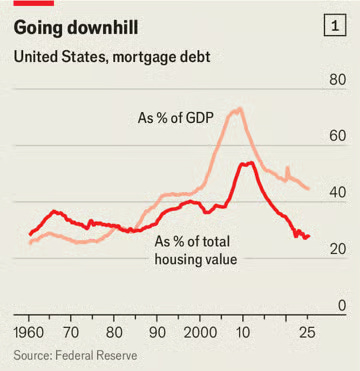

For all the talk of bubbles in equity markets, private credit and elsewhere, the market that hosted the last great bubble has been quiet. It’s still vast: At roughly $13.5 trillion, more mortgage loans are outstanding than corporate bonds in the US. But its footprint has been shrinking. As The Economist notes this week, mortgage balances have fallen by almost 30 percentage points relative to the size of the economy since the peak of the last boom, taking them back to late-1990s levels. Set against the value of American homes, the decline looks even starker: mortgage debt now amounts to barely a quarter of household real-estate wealth, the lowest share in more than six decades.

For mortgage bankers, this didn’t initially pose much of a problem. As long as interest rates were drifting lower, they could rely on a steady stream of refinancing. Every decline in rates invited borrowers to reshuffle their loans, creating new mortgages even when nothing new was being financed. It was flow without growth – and for years it kept the business humming. When rates fell to almost unimaginable lows in 2021 – touching 2.65% on a 30 year fixed-rate mortgage – originations swelled to $4.4 trillion, more than twice their usual level, handing a windfall to the bankers who sat in the middle.

But with rates now above 6%, those days are long gone, and refinancing activity has collapsed. Intercontinental Exchange, owner of a mortgage technology platform, estimates that at current rates, there are 1.7 million borrowers out there with capacity to refinance. That’s up from a few years ago, but it’s way down on the 17

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.