And Also With You

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Robert Morrison (missionary)

14 min read

The article mentions Morrison as the first Protestant missionary to China in 1807, but doesn't elaborate on his remarkable story of creating the first Chinese-English dictionary and translating the entire Bible into Chinese—foundational work that enabled the poster-based evangelism discussed in the article

-

Hui people

11 min read

The article references posters tailored to 'Hui Muslims' combining Mandarin with Arabic script, but doesn't explain who the Hui are—a Chinese Muslim ethnic group with a fascinating history of integrating Islam with Chinese culture over 1,400 years, providing crucial context for why missionaries would target them specifically

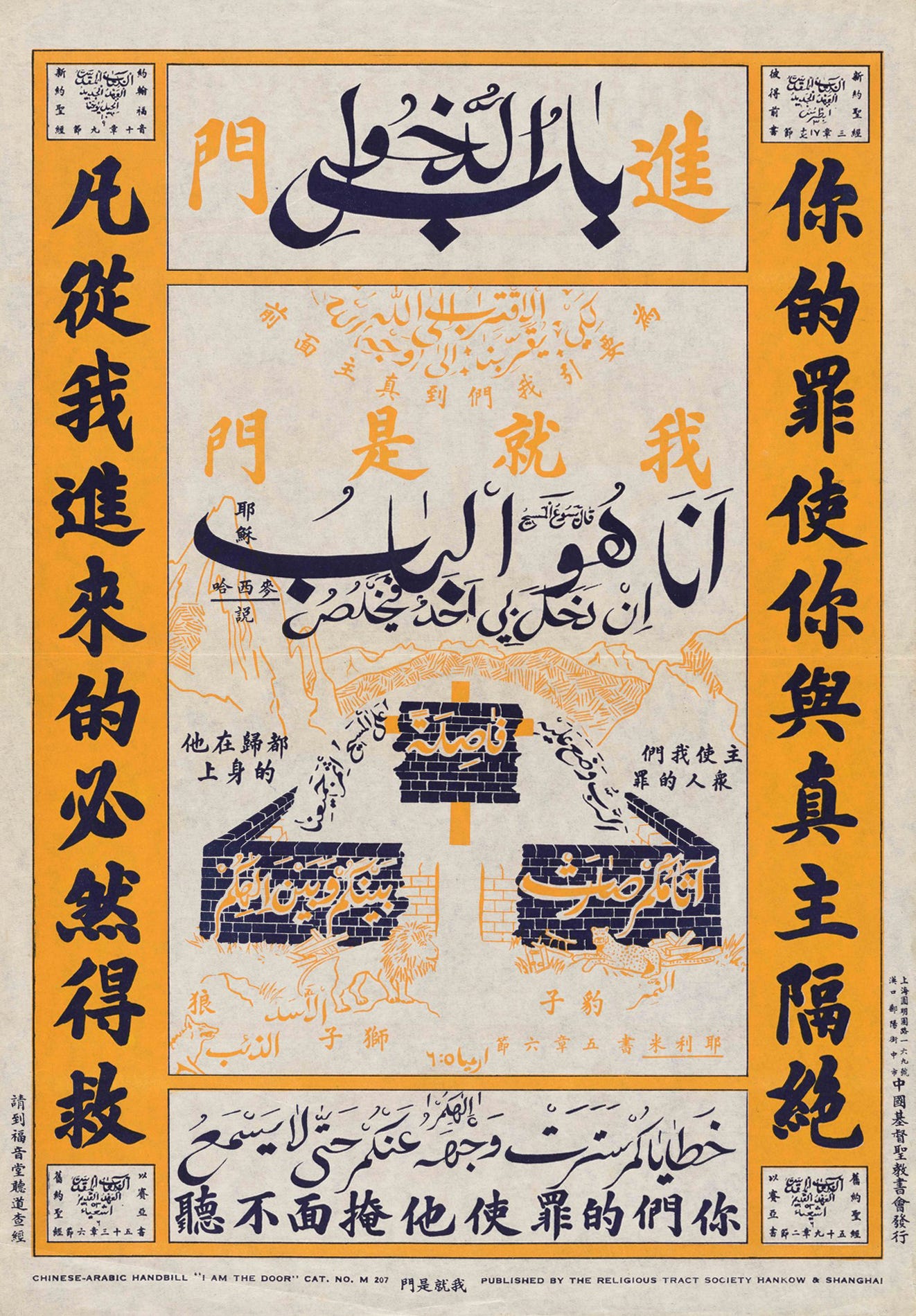

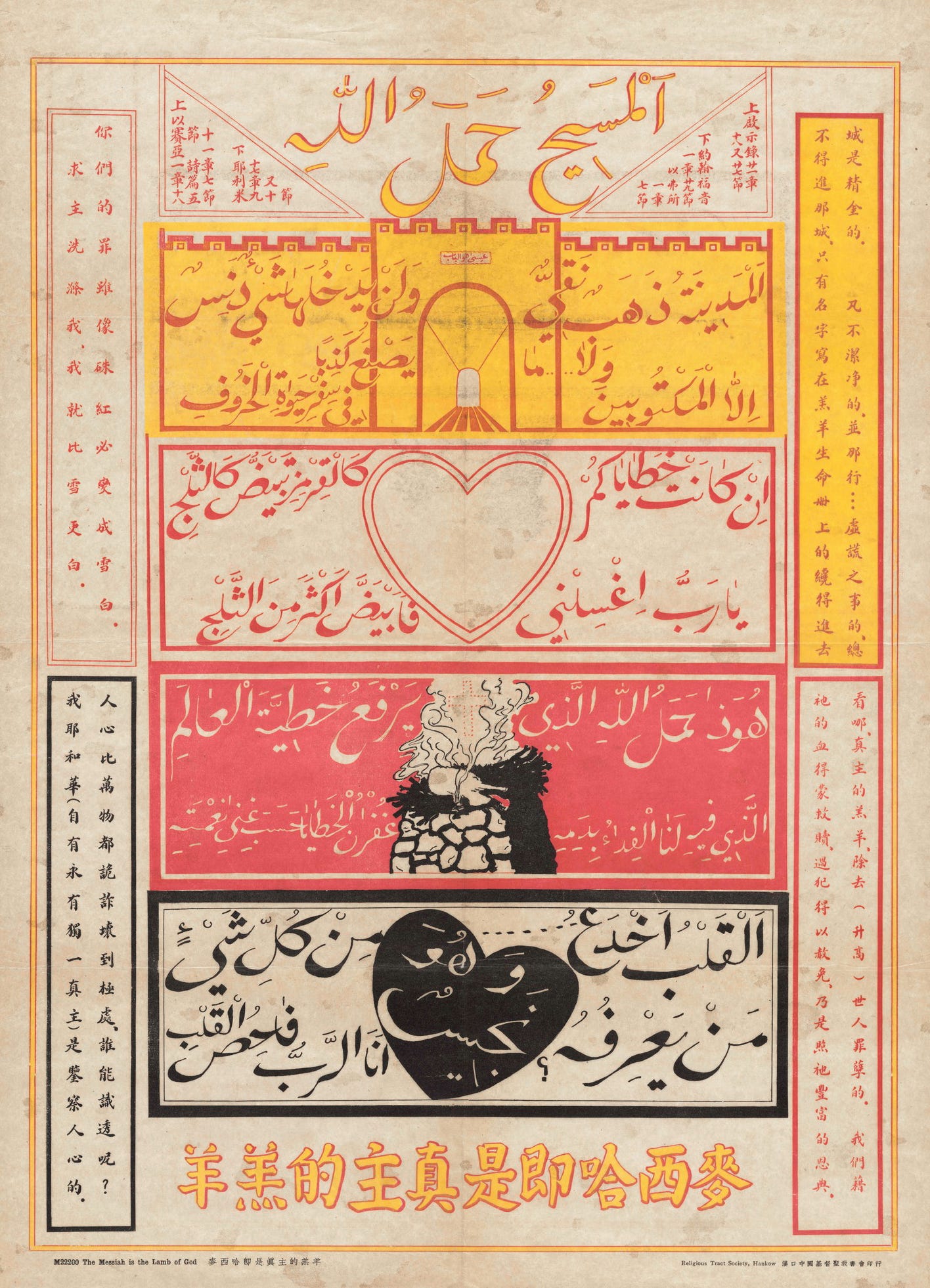

Today’s collection is a set of Christian propaganda posters printed and distributed across China from the late 1920s to the early 1950s. While missionaries had been traveling to China for over a century by the time posters like these first appeared (the first Protestant missionary, Robert Morrison, arrived in 1807), during the Republican era from 1911–1949, the country’s fractured leadership and ideological clashes created an especially ripe opportunity for missionaries to spread their message before another government took hold. Street preaching was common but often ineffective: language barriers and competition for attention limited speakers’ reach, and in most regions, public evangelism was seen as disruptive, aggressive, and even embarrassing. Posters, on the other hand, could be disseminated widely in a range of languages and more easily integrated into public Chinese life.

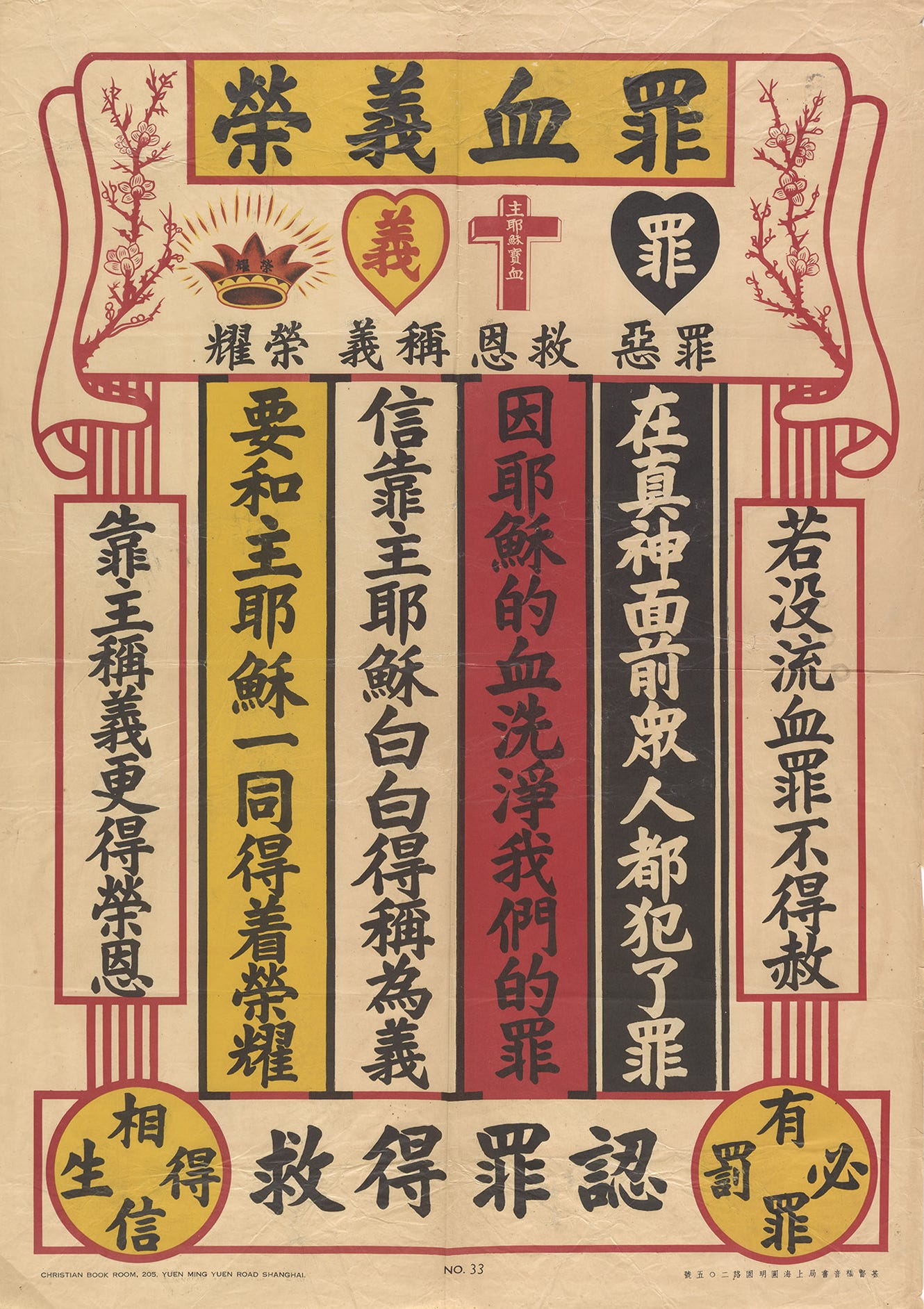

These posters were created by missionary organizations and Chinese Christians alike, and covered religious doctrine and Bible stories as well as advice on subjects as myriad as admitting wrongdoing, killing flies, and proper air circulation during sleep. Their remit was difficult—they needed to introduce radical ideas, visually compete with more familiar political and religious ephemera, and also be affordable to print at a large scale and in large quantities. The result was a style defined by symbolic density—combining Western imagery like crosses and sacred hearts with Chinese iconography like abaci, lotus flowers, and zodiac animals—bold, minimal color palettes, and confident typography.

Many remapped familiar Chinese visual traditions onto Christian content: the Virgin Mary rendered as a Ming dynasty noblewoman, or a guide to communion designed with flattened perspective and decorative framing reminiscent of Buddhist cosmological diagrams, which use segmented layouts to structure complex moral or metaphysical ideas. Other posters were tailored to specific minority groups, such as the Hui Muslims, and combined Mandarin with Arabic or Tibetan script to proselytize across languages and faiths.

While the densely illustrated posters are more visually rich, I find myself most drawn to the simplest posters, like the ones I included here. They make clear how little it takes (visually, at least!) for a message to assert itself, even across unfamiliar ground.

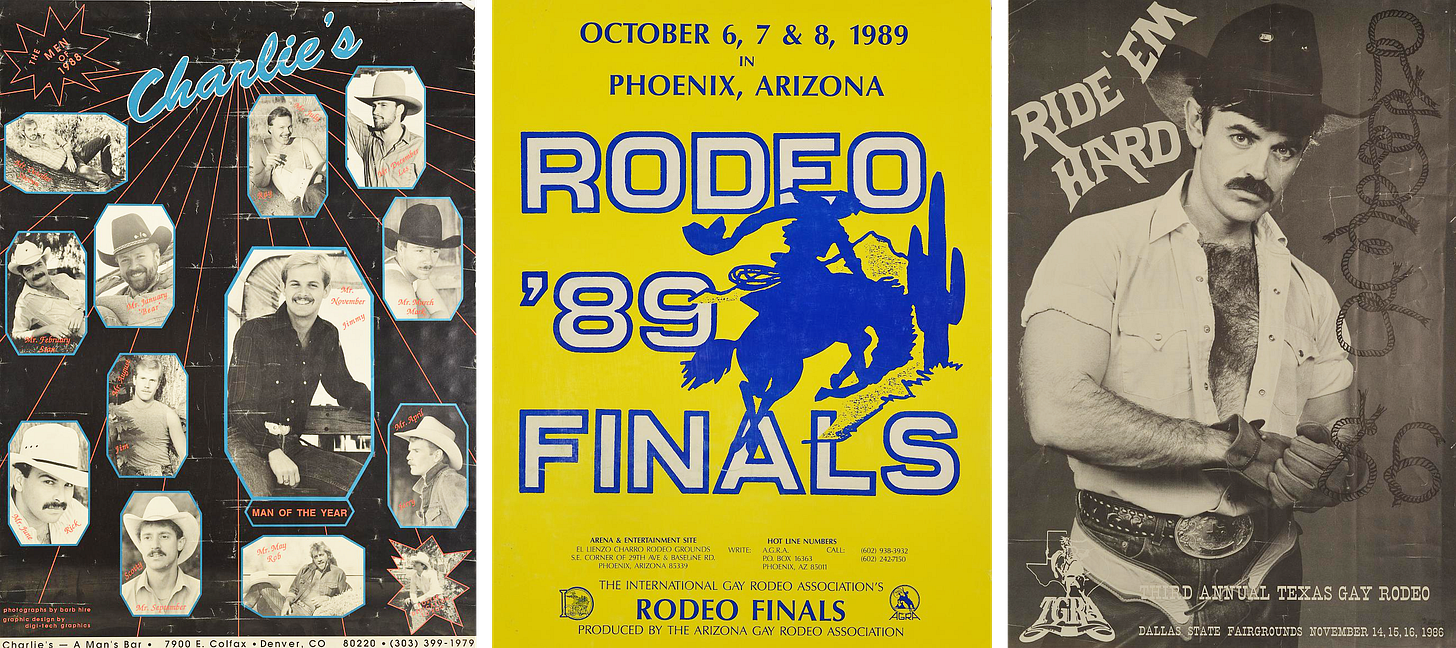

Just too late for Pride: this issue’s featured archive is the the Gay Rodeo History archive. I feel that this one is relatively self explanatory, and if the name alone does not warrant a click, I really don’t know how to help you.

Someone once told me

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.