Into the Golden Era of Chinese Animation

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Shanghai Animation Film Studio

13 min read

The article centers on an exhibition about this legendary studio, which pioneered Chinese animation from the 1950s-1990s. Readers would benefit from understanding its full history, notable films, and artistic innovations that made it influential.

-

Havoc in Heaven

15 min read

The article features a still from 'Uproar in Heaven' (1964) and mentions animator Yan Dingxian working on it. This landmark film adapted from Journey to the West is considered one of the greatest achievements in Chinese animation history.

Welcome! It’s another Thursday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter — and this one’s about China.

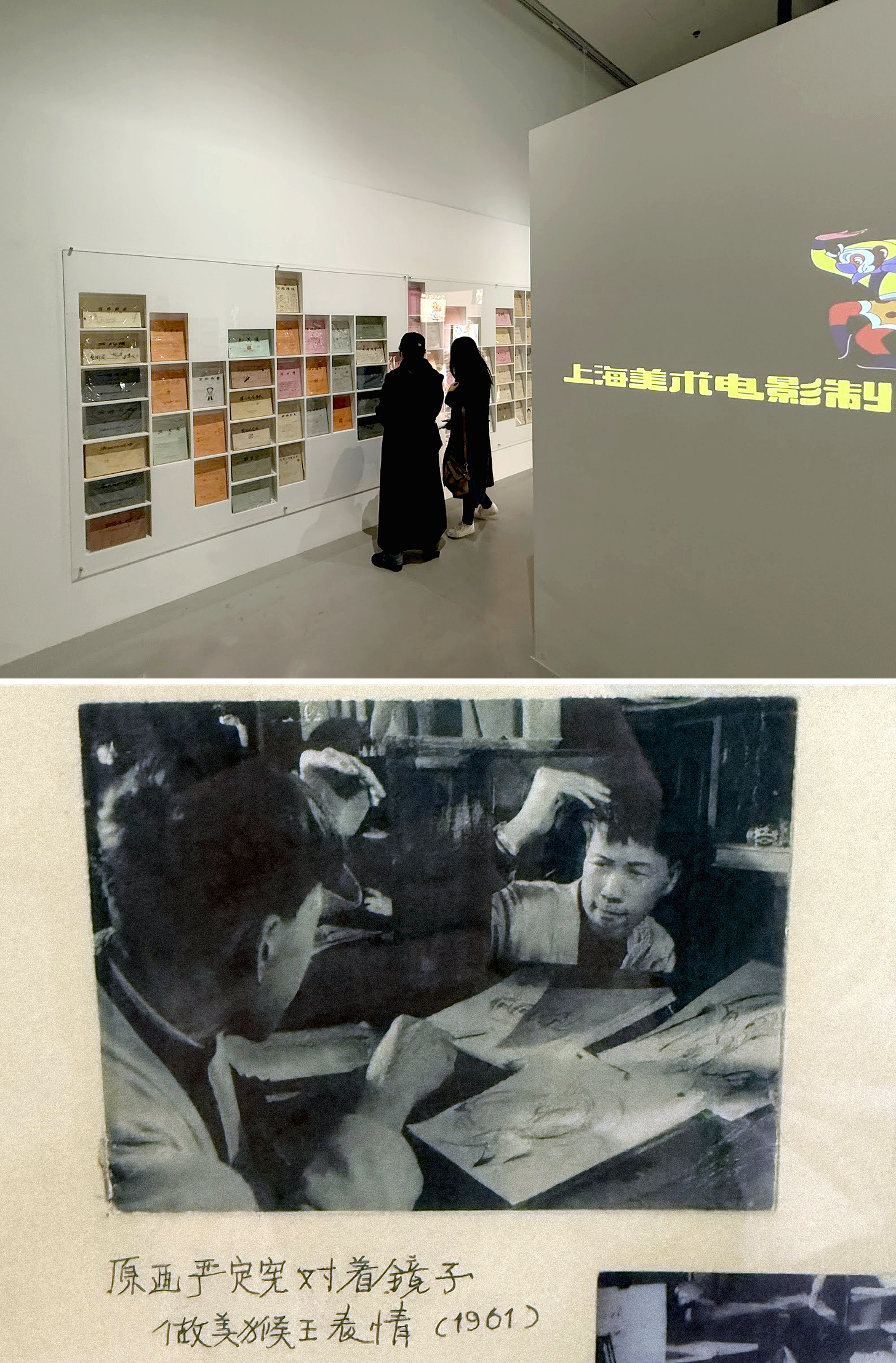

An exhibition wrapped up in Beijing last month. Its title was Animating China. Visitors toured the history of the country’s animation — with a heavy focus on the great Shanghai Animation Film Studio. Behind the show were some of the best researchers of this medium in the world, including scholar Fu Guangchao.

We couldn’t go. Even so, today’s issue is an on-the-ground report from the event.

A writer messaged us just before Animating China ended — Rachel Zheng, formerly with Vice China. She wanted to cover the show for us. The newsletter doesn’t often run commissioned pieces (we’ve only published two this year), but her idea was too interesting not to accept. And it’s our story today.

Rachel tackles this topic in layers: the exhibition itself, and how it’s tied to art history, and to personal history, and to China as a whole. We’re very excited to share her account of Animating China — and we’ll let her take it from here!

On a blissful Beijing autumn day, the best season in the city, I biked past the glass edges of the central business district and arrived at the Taikang Art Museum. It was the final day of the Shanghai Animation Film Studio exhibition — my second visit, and my last chance to return to a childhood of distant memory.

Families of different generations crowded around the screens. A father pointed proudly at Nezha Conquers the Dragon King (1979) and declared to his children, “Today the characters only look flashier, move faster. Back in my days, animations had soul.”

The father’s words resonated with me. What I didn’t know growing up was why these animations felt so alive, why they seemed so real and lingered in our minds. But perhaps this was the chance to find out.

This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.