Women in the Kitchen, Part 2

"Certainly cooking for oneself reveals man at his weirdest," Laurie Colwin noted in Alone in the Kitchen With An Eggplant. (It’s one of my favorite essays in Home Cooking).

These days cooking for yourself may not seem weird - but it is often seen as selfish. Why go to all that trouble just for yourself?

That's why I appreciate Corned Beef and Caviar, written by the great Marjorie Hillis almost 90 years ago. (Hillis, an editor at Vogue, was the Carrie Bradshaw of her time. Her Live Alone and Like It, a manifesto for the single woman, was a runaway best-seller in 1936. This book, published the following year, was even more popular.)

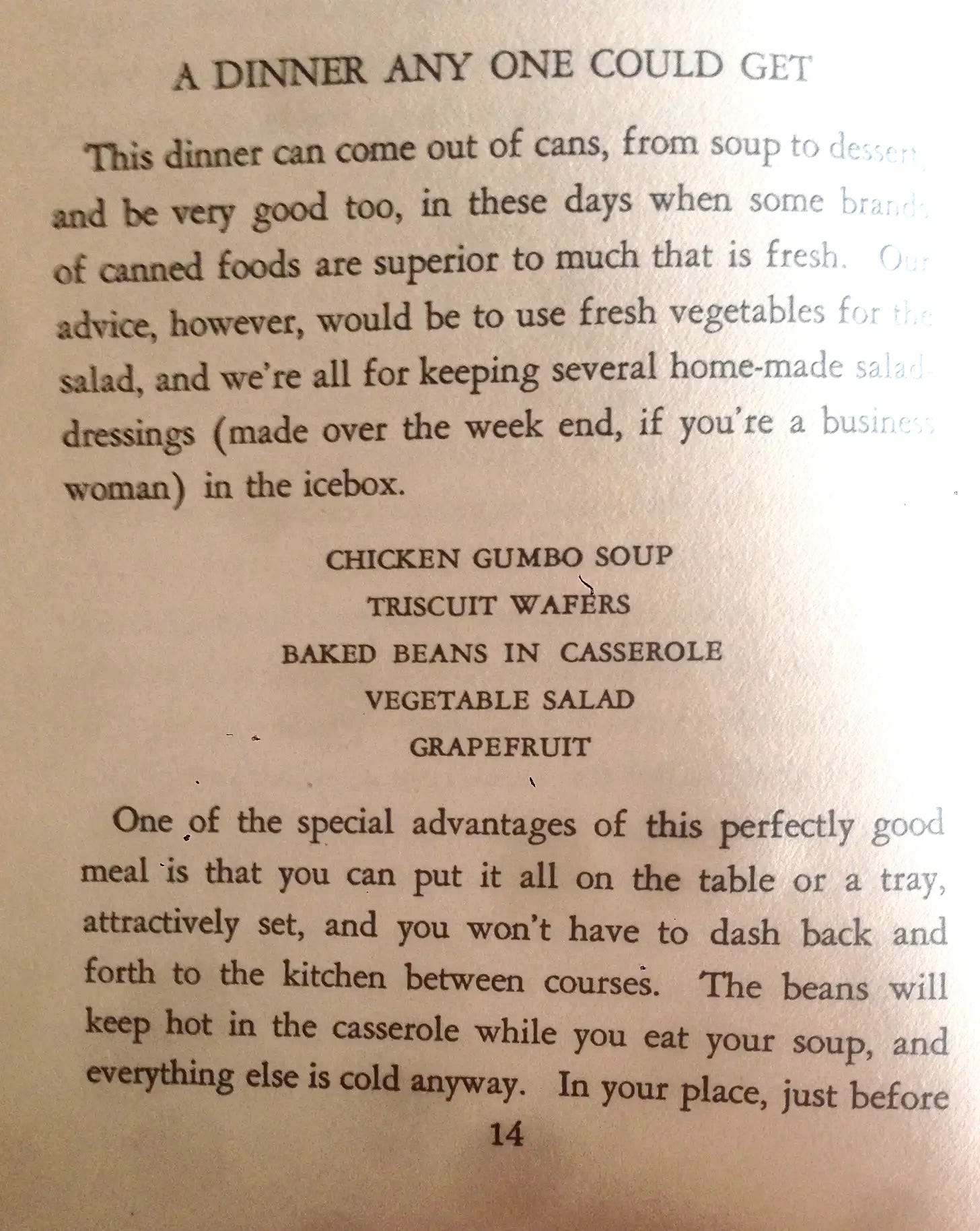

This "recipe" is not really about cooking: it is a lesson in cultivating solitary rituals. It strikes me as remarkably modern.

If you want to know more about Ms. Hillis, there is an excellent book about her called The Extra Woman.

And here’s the opposite, from a 1947 book that makes my blood boil.

The author, Dorothy Malone, was one of a large group of woman (mostly home economists) who wrote for the Hearst newspapers under the pseudonym Prudence Penny. At one time there were thirty different women across the country writing as Ms. Penny.

I imagine they all turned out copy like this little essay which suggests that the first ingredient for a successful breakfast is essentially you, the reader, the new wife, all dewy and well-groomed.

Don’t you wish you had a breakfast coat?

I assumed the whole book would drone on in this fashion, but then I got to the section called, "We deal in trickery." Reading it I was almost ready to forgive Ms. Malone. "If your cake has fallen, don't grieve for a second. A fallen cake is always richer."

The recipes, I might note, strike me as what my friend Zanne calls “throat-closers.”

Those books made me a remember a group of French woman chefs who came to Los Angeles in 1985. They represented a group called ARC- Association des Restauratrices- Cuisinières- women chef/owners who were fed up with accepting the notion that only men could be great chefs. “Why,” one of them asked me, “should the award be called Meilleur Ouvrier de France? Why not ouvrière?”

Despite their efforts it would be more than twenty years until the first woman

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.