Propaganda of the Creed

Christianity, whilst not entirely alien to violence, has been at the root of historical pacifist and pacifist-adjacent movements1 throughout all creation. For as long as there have been Christians, there have peace movements that attempt to bring peace into the world and, either through optimistic muddleheadedness or questionable political imposition, turn the world to the peace of Christ. These tendancies proceed on many fronts, but the most central of them include Christ’s own example and proclamation of non-resistance (e.g., Matthew 5:21-25, 38-48) as well as the fundamental egalitarianism at the heart of recognising everyone as first a sinner and then as one who can become faithful by their own free will with the universalising help of God2. Along with the influence that Christ breathed into MLK in the civil rights movement and into Gandhi in the quest for Indian independence, the fundamentally religious basis of the strength in refusing to wield arms against the neighbour, even in his most unlovable moments, is one of the firmest groundings to date.

The historical anarchist movement, of course, was not unfamiliar with this. According to one researcher, Benjamin Pauli, in fact, there was a post-war turn towards pacifism and pacifist-adjacent tactics and overarching worldviews across the globe. But can the anarchist wield this position faithfully or does it devolve into the comfortable security of a “radicalism” that asks nothing of the world? Could the Christian, in this context, faithfully endure towards pacifist-like ends or will they collapse into the secular degradation that litters history? For this, we start first with those anarchists who were not so ready to wield peace against evil—and how these thinkers, when we follow their bloodied letters downstream, have affected secular peace in a secular world that marches according to the “ontology of violence”3.

On the Degradation of the Deed

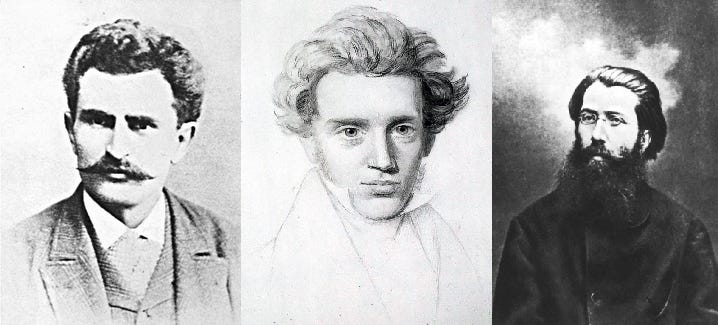

In reflecting more on the broader history of anarchist radicalism, Pauli’s article, “Pacifism, Nonviolence, and the Reinvention of Anarchist Tactics in the Twentieth Century”4, lays out the historical development of Brousse’s “propaganda of the deed”5, i.e., to do is greater than merely to write. Pauli writes:

...Propaganda of the deed sought to render abstract concepts and ideals concrete, enabling everyday people to confront them in a tactile, empirical way. Carrying out propagandistic actions

This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.