The cicada, the octopus, and the tortoise

Life is weird. So is time. So is the wide range of animal lifespans and life histories (when they mature, reproduce, age, morph, and die).

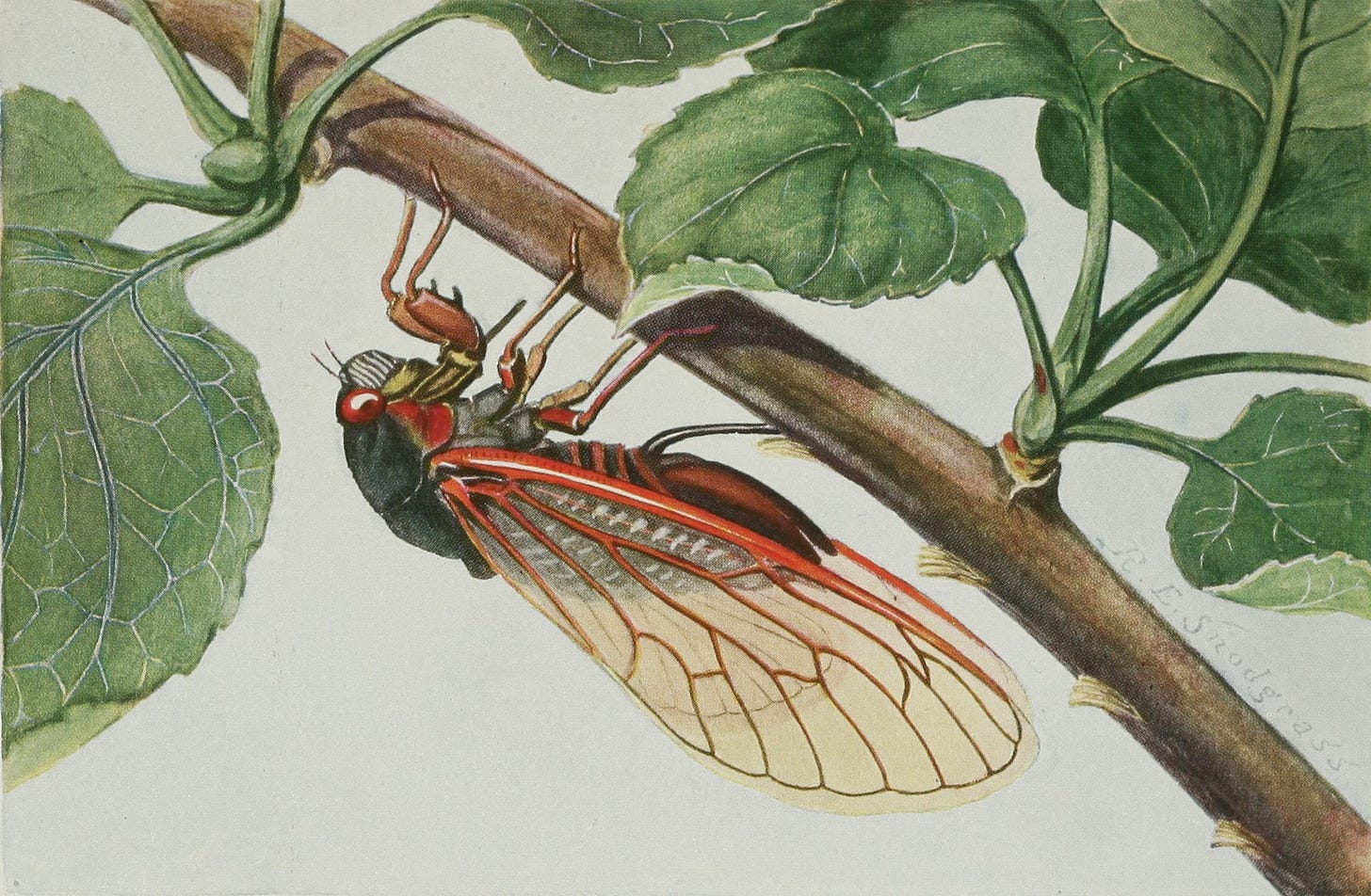

Right now in parts of the U.S. Midwest and Southeast, two broods of periodical cicadas are emerging (there are seven such North American species in the genus Magicicada). Periodical cicadas are a small minority of the thousands of documented species, nearly all of which are annual cicadas. Loud bugs? What’s remarkable about that?

Well, for starters these are exceptionally large broods—known as XIII and XIX—numbered in billions. Slightly confusingly, they are rising above ground for the first time in 17 and 13 years, respectively. Because of their precise cycles, the last time these two broods co-emerged was in 1803.

After spending their juvenile years developing underground, they emerge in sync to transform into adults, mate, and lay eggs. The distinctive buzzing drone of the cicada chorus is produced by large groups of males, each singing a mating song to attract females. (Wild Animal Initiative)

Two things are puzzling about these insects. Why do they spend so much time underground? And why is the emergence of a brood synchronous? The synchronicity of the current co-emergence of the two broods is not puzzling, it follows mathematically from the within-brood synchronicity (though for good measure, evolution threw a wrench in that regularity with also occasional four-year jumps in development that result in switches between 13- and 17-year cycles). The most common hypothesis is that these two puzzling facts minimize predation risk—reduced availability to predators selects against predators that may have evolved to depend on them and large-scale emergence compensates for whatever predation does happen simply by offering more than predators can chew (satiation).1 However, it remains puzzling to me why, if the strategy pays off, it is so unusual among cicadas. Annual cicadas have not gone extinct despite making themselves regularly available, in more digestible numbers, to potential predators.

Periodical cicadas spend 99.5% of their unusually long lives underground, enjoying an abundance of food and a relative lack of predators. It’s likely that predation becomes a serious threat only in the final few weeks of their lives, when they emerge and become adults. (Wild Animal Initiative)

Not much is known about their life underground for all these years. But imagine: most

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.