Animalcules and Their Motors

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Universal joint

12 min read

Linked in the article (12 min read)

-

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

12 min read

The article opens with Leeuwenhoek's discovery of microbes but only briefly sketches his biography. A deep dive into the 'Father of Microbiology' - his self-taught lens-grinding techniques, correspondence with the Royal Society, and the hundreds of microscopes he built - would provide rich historical context for understanding how this cloth merchant revolutionized biology.

-

Flagellum

13 min read

While the article describes flagellar motors in fascinating detail, readers would benefit from a comprehensive overview of flagella across all domains of life - their evolutionary origins, the distinct mechanisms in bacteria vs. archaea vs. eukaryotes, and their role in pathogenesis. This provides the broader biological framework for the article's focus on bacterial motor structures.

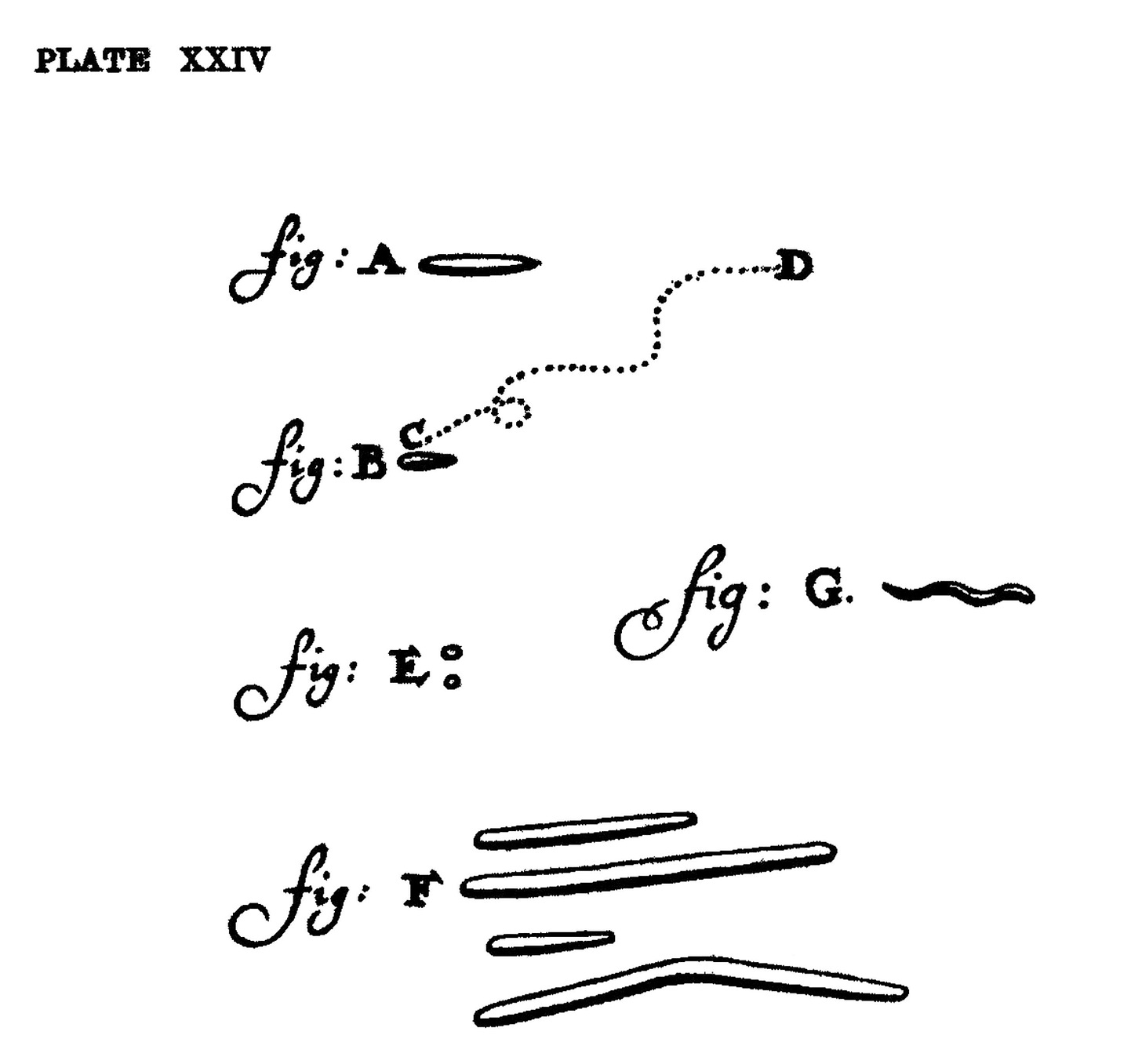

In 1674, a Dutch cloth merchant in Delft, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, spent his free time tinkering with lenses. One day, he pressed a drop of rainwater beneath his homemade microscope and observed what he called “animalcules” darting about. Leeuwenhoek described these creatures in two letters he sent to the Royal Society in London for publication, each replete with charming descriptions:

[T]he motion of most of these animalcules in the water was so swift, and so various upwards, downwards and round about that ‘twas wonderful to see: and I judged that some of these little creatures were above a thousand times smaller than the smallest ones I have ever yet seen upon the rind of cheese.

Leeuwenhoek may have been the first person to see microbes in motion, but his microscopes weren’t powerful enough to see the actual machinery responsible. (Leeuwenhoek mused that his animalcules might be using “little paws” to move.) It wasn’t until the 1830s that a German naturalist, Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg, saw whisker-like appendages, later named flagella, protruding from microbes. Still, the mechanism by which they worked remained unknown until the latter half of the 20th century, when electron microscopes finally homed in on the thousands of proteins that make a flagellar motor, able to convert flowing protons into mechanical motion.

Even more recently, a surge of research has revealed how evolution has finetuned the flagellum to operate in vastly different ways based on a cell’s niche. Whereas an E. coli flagellum spins around nearly 20,000 times per minute, the flagellum in a microbe called Vibrio alginolyticus spins about five times faster, or slightly more than 100,000 times per minute. (For context, a Boeing 737 rotor has a maximum speed of 14,000 rpm.) This extra rotary speed is because Vibrio cells must traverse the ocean, where ion gradients (used to drive the motors) are large and nutrients more spread out.

A microbe found in the human digestive system, Campylobacter jejuni, also has a flagellar motor that generates much more torque than the one in E. coli — about 3,600 piconewton-nanometers. It uses this higher torque to propel itself through the viscous environment of the

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.