Why is South Korean fertility so low?

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Hagwon

10 min read

The article extensively discusses hagwons as central to South Korea's education arms race and their role in the fertility crisis. A deep dive into this institution's history, structure, and societal impact would give readers crucial context for understanding the parenting pressures described.

-

Demographics of South Korea

11 min read

Provides historical context for the antinatalist campaigns mentioned in the article, plus demographic data on marriage rates, birth rates over time, and population projections that frame the current crisis.

-

Motherhood penalty

15 min read

The article discusses the severe earnings penalty for Korean mothers (66%) compared to other countries. This Wikipedia article explains the broader phenomenon, research behind it, and cross-country comparisons that contextualize why Korea's penalty is so extreme.

This article originally appeared in the first print issue of Works in Progress. Subscribe to get six full-color editions sent bimonthly, plus invitations to our subscriber-only events.

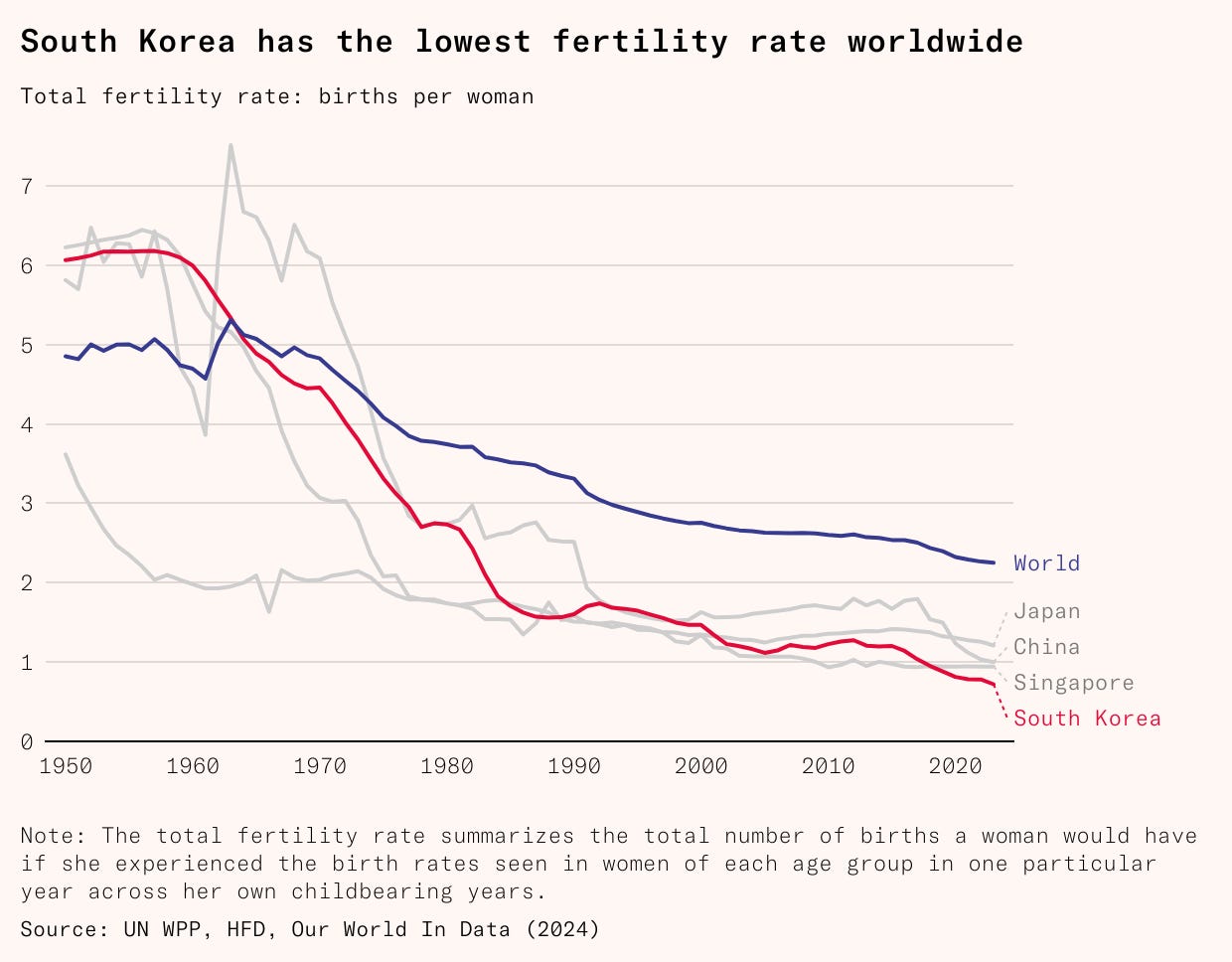

South Korea has the lowest fertility rate in the world. Its population is (optimistically) projected to shrink by over two thirds over the next 100 years. If current fertility rates persist, every hundred South Koreans today will have only six great-grandchildren between them.

This disaster has sources that will sound eerily familiar to Western readers, including harsh tradeoffs between careers and motherhood, an arms race of intensive parenting, a breakdown in the relations between men and women, and falling marriage rates. In all these cases, what distinguishes South Korea is that these factors occur in a particularly extreme form. The only factor that has little parallel in Western societies is the legacy of highly successful antinatalist campaigns by the South Korean government in previous decades.

South Korea is often held up as an example of the failure of public policy to reverse high fertility rates. This is seriously misleading. Contrary to popular myth, South Korean pro-parent subsidies have not been very large, and relative to their modest size, they have been fairly successful.

The story of South Korean fertility rates is thus doubly significant. On the one hand, it illustrates just how potent anti-parenting factors can become, creating a profoundly hostile environment in which to raise children and discouraging a whole society from doing so. On the other, it may offer a scintilla of hope that focused and generous policy can address these problems, shaping a way back from the brink of catastrophe.

Career-motherhood conflict

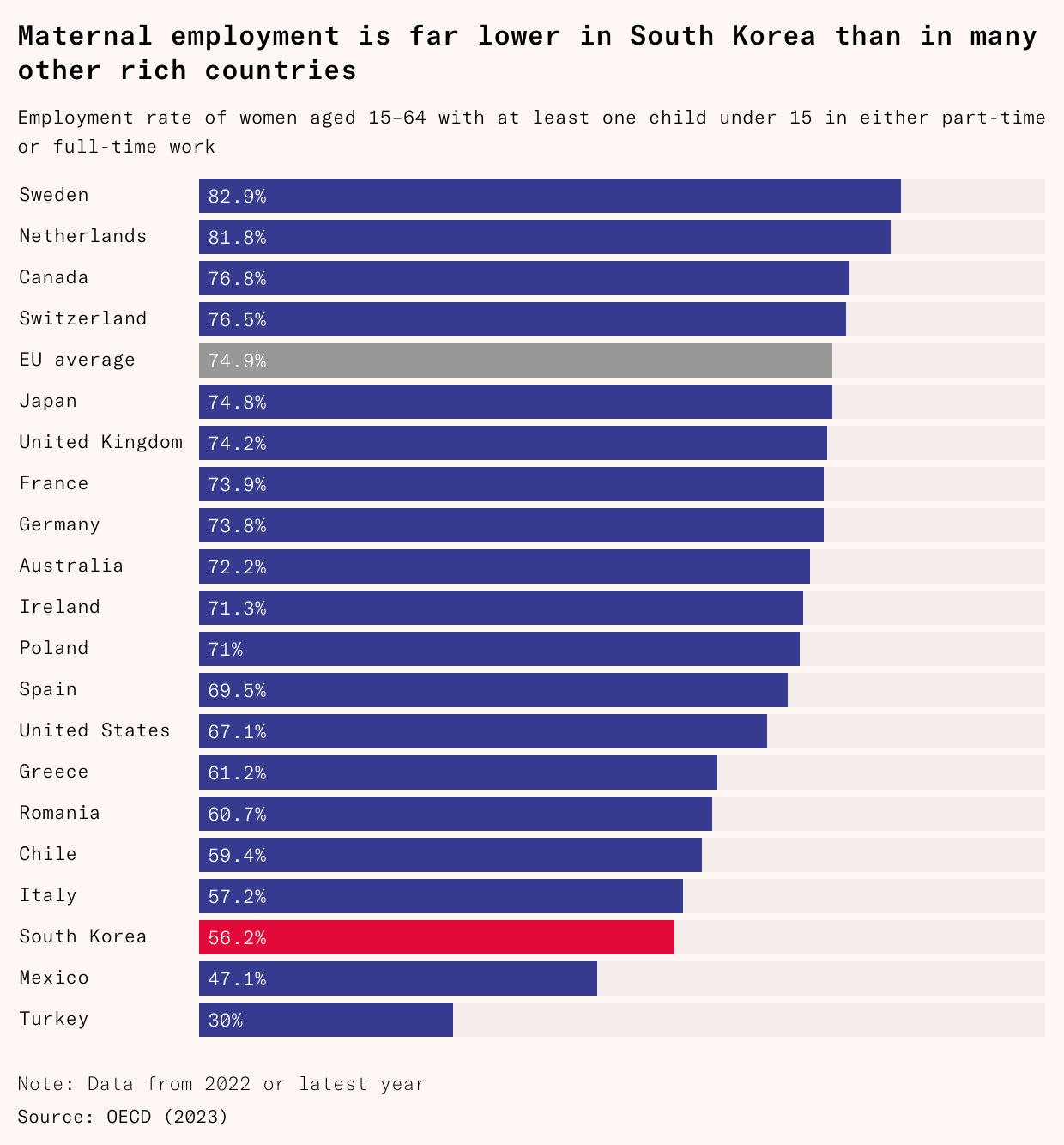

In every developed country, women struggle to reconcile their careers with a satisfying family life and their preferred number of children. This tradeoff is exceptionally severe in South Korea.

Despite its very high level of female education, South Korea has the largest gender employment gap in the OECD. There is almost no employment gap between men (73.3 percent) and unmarried women without children (72.8 percent). The gap is driven by the fact that large numbers of women stop working when they have kids: only 56.2 percent of mothers work, the fourth lowest in the OECD.

In South Korea, mothers’ employment falls by 49 percent relative to fathers, over ten years – 62 percent initially, then rising as their child ages. In the US it falls by a quarter

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.