When Anti-Fascism Becomes Liberal Discipline

In a recent essay titled How Can We Live Together, philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò contends that Ezra Klein’s call for open debate with the right—following the assassination of Charlie Kirk—ultimately “plays into the fascist script.” Táíwò argues that we should follow Bertrand Russell’s example in refusing to debate Sir Oswald Mosley—the founder of a literal British fascist party and outspoken fascist public figure—warning that liberals will only play into the rise of fascism by engaging in debate and that the proper response to the right is instead to shame them. The fact that Mosley is compared to Charlie Kirk—we are left to assume that Turning Points USA is a fascist group—tells us immediately where Táíwò stands on the debate as to whether Trump is a fascist.

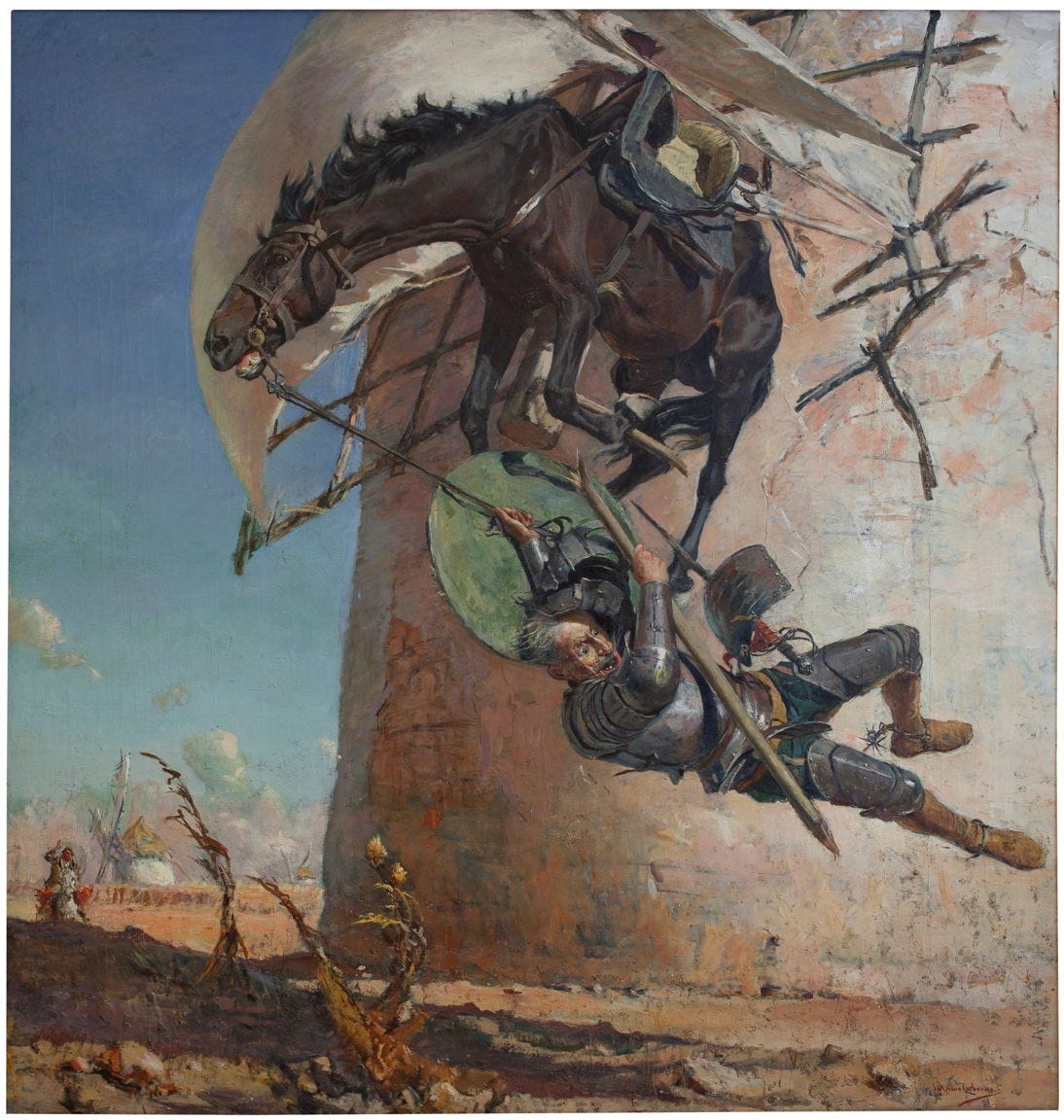

While I agree in principle that self-declared fascists should not be debated, I reject a policy of strict no-platforming, because I have seen how it corrodes the left and weakens socialism. It produces what I call the Quixote Syndrome — a condition in which the left becomes more preoccupied with policing who is allowed to speak, with managing discourse itself, than with actually confronting the fascist threat. I want to argue that this is the inevitable outcome of a left aligned with liberalism: the fascist threat becomes a quest of tilting at windmills, where everything is labeled fascist, all distinction between reactionary tendencies collapses, and anti-fascism devolves into the policing of vibes and affects — applied not only to the right but increasingly to the left itself. The Quixote Syndrome leads to a scenario in which Marxists who speak of class and the working class — or even populist publications like Compact Magazine, or class-first thinkers such as Adolph Reed, Vivek Chibber, Catherine Liu — are cast as enemies, treated as indistinguishable from fascists. This is what left-liberal unity produces: a regression into an upper-middle-class, hyper-liberal politics that views working-class people in the same patronizing manner that liberal centrists view someone like Graham Platner today. That is the path I fear we are walking toward if we continue down the road of left-liberal unity.

While Táíwò acknowledges that “politically correct” politics stretching back to the 1990s and its more excessive successor “woke politics” which took off in the 2010s both ‘overreached’ and that they are out of step with

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.