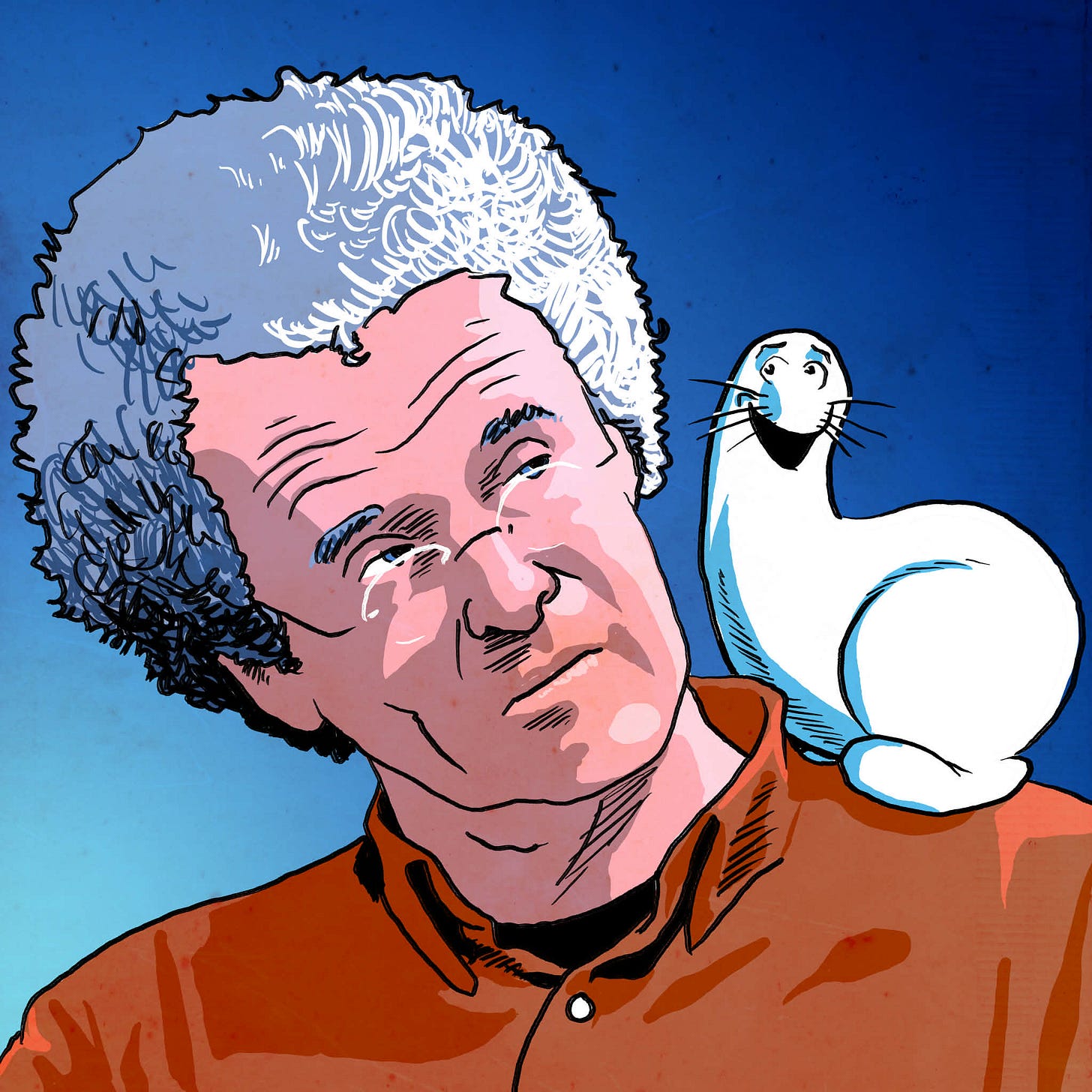

Erik Olin Wright and the Lessons of the Shmoo

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Erik Olin Wright

11 min read

The article centers on Wright's theories of exploitation and class analysis from his book Class Counts. Understanding his broader intellectual contributions to analytical Marxism and sociology would deepen the reader's appreciation of the theoretical framework being discussed.

-

Li'l Abner

15 min read

The shmoo parable that Wright uses comes from this influential comic strip. Understanding the cultural context of Al Capp's satirical hillbilly comic and its mid-20th century social commentary would illuminate why Wright chose this particular example.

-

Analytical Marxism

13 min read

Wright is described as an 'analytical Marxist thinker' and this intellectual tradition shaped his rigorous, systematic approach to exploitation theory. Understanding this school of thought helps contextualize his methodological approach.

There are many ways in which one section of a society can dominate or oppress another. Not all of these count as forms of exploitation, at least if that word is used in anything like a Marxist way.

There can even be forms of non-exploitative economic oppression. If a group is systematically denied employment and thus lives a precarious existence on the edges of society, begging or stealing enough to stay alive, they’re certainly being economically oppressed. In fact, there’s a pretty clear sense in which they’re more economically oppressed than working-class people with secure and comfortable jobs. But, they’re not being exploited.

In his book Class Counts, the sociologist and analytical Marxist thinker Erik Olin Wright offers a complicated three-pronged definition of exploitation:

The “material welfare” of one group “causally depends on the

material deprivations of another.”

In other words, Group A is better off because Group B is worse off. If Group A are the beneficiaries of inherited wealth, Group B are not, and there’s simply no economic interaction between the two, this condition isn’t met. Ideals of egalitarian justice might demand redistribution from A to B, and you could stretch and say that A is better off than B because this hasn’t happened yet so in that sense they’re better off “because” B is worse off, but Wright is clearly holding out for a more robust causal connection than that.This causal relation involves the exclusion of the exploited group “from access to certain productive resources.”

In the case of slaves (wholly) and serfs (partially), the exploited group are excluded from control over themselves. Modern proletarians aren’t excluded from that productive resource, but they’re excluded from control over the means of production. That’s what makes them “doubly free” in Marx’s acid formulation in Capital—free to move around and make contracts with any capitalist who will have them, but also “free” from any realistic way of supporting themselves except submitting to one capitalist or another.The “causal mechanism which translates” this exclusion into the difference in welfare between the groups “involves the appropriation of the fruits of labor of the exploited by those who control the relevant productive resources.

So, whatever the details in a particular economic system, the end result is that some of what’s produced by the exploited group ends up in the hands of the exploiters. Even if both of the

This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.