Low-Income Countries are Falling Behind

Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 47,000 people who read Apricitas!

Over the last forty years, the world has made historic progress in reducing the scourge of global poverty. The share of the human population living in extreme poverty (less than $2.15 a day) has fallen from more than 40% to less than 10% within a generation, lifting hundreds of millions of people out of acute suffering. Yet progress has been too slow—and even worse, it has now stalled.

The COVID-19 pandemic, ensuing inflation, and the rise in international conflict have made it so that global extreme poverty rates have actually risen over the last four years. Declines in the less-extreme forms of global poverty more common in middle-income countries have continued but at a much slower pace than during the 2010s. Unless something changes, institutions like the World Bank warn of a possible “lost decade” for the war on global poverty.

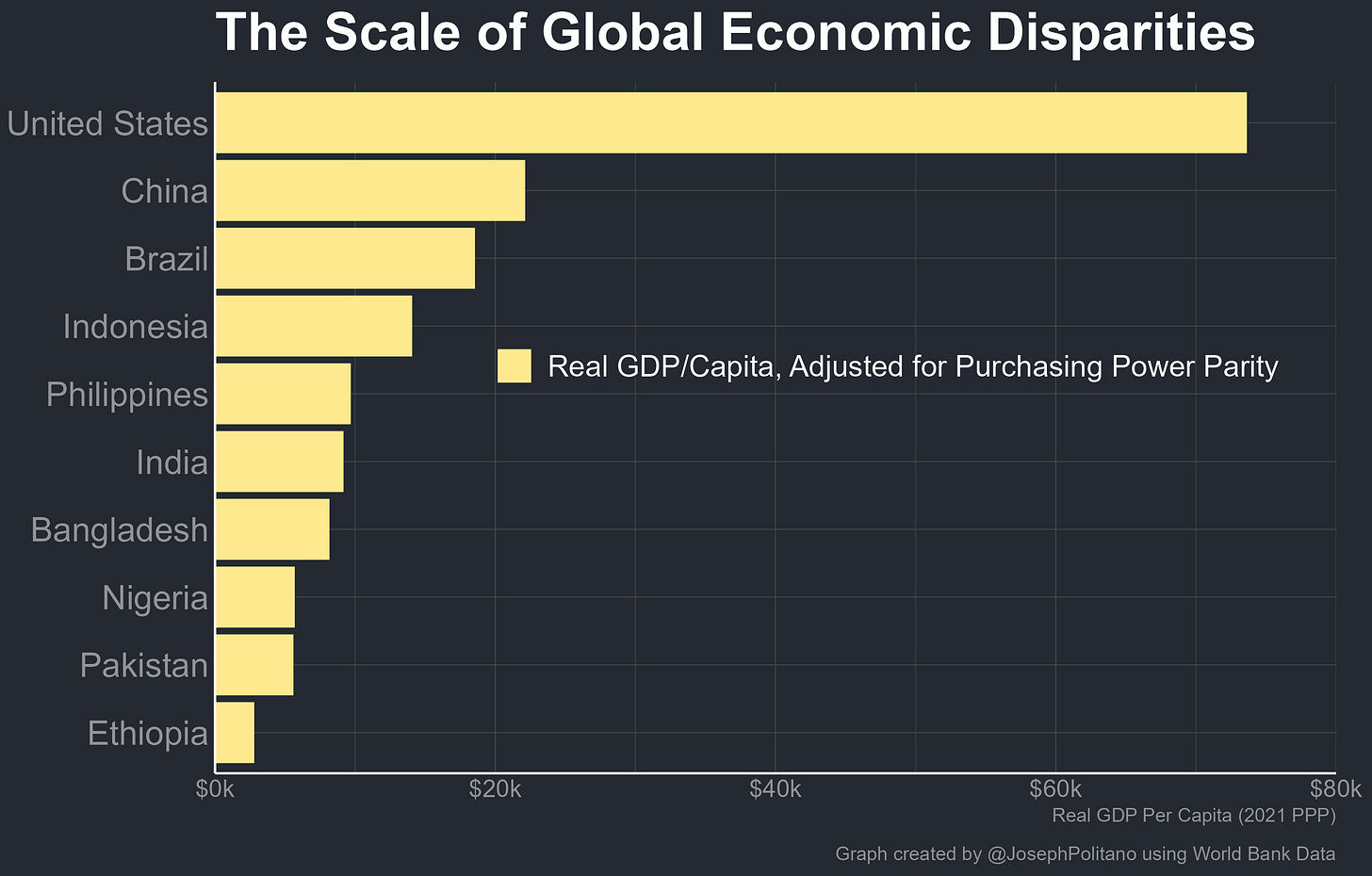

That would be a disaster given the massive existing disparities within the global economy. Annual per-capita output in the United States, the world’s largest frontier economy, is $73k—roughly 26 times the average for the low-income countries where 766M people currently live. Even lower-middle-income countries like India, Nigeria, and the Philippines average only one-ninth America’s economic output. That lower GDP represents less consumption of food, healthcare, and technology, less investment in infrastructure, education, and housing, and less general welfare for billions of people across the globe. Indeed, between-country economic inequality is so large that the 10th percentile of American income is two and a half times as much as the 90th percentile of Indian income.

To reach high living standards, low and middle-income countries must achieve “economic convergence”—not only growing their economies but growing them substantially faster than frontier countries like the US so they can “catch up”. A relatively-normal 2.5% increase in US economic output would deliver an average of $1,800 a year extra to Americans, but to achieve those same dollar gains Sierra Leone would need to more-than-double the size of its economy. Yet much of classical economic theory predicts countries like Sierra Leone should swiftly converge with the US—after all, frontier economies have to earn most of their growth by making difficult discoveries along the scientific frontier, while low-income countries can make substantial gains through rapid deployment of existing technologies like trains, phones, electricity,

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.