The Tower of Science

This is a guest post by Hiya Jain, a recent Columbia University graduate with a keen interest in science policy and the history of science. You can find more of her writing on her Substack, Mundane Beauty.

***

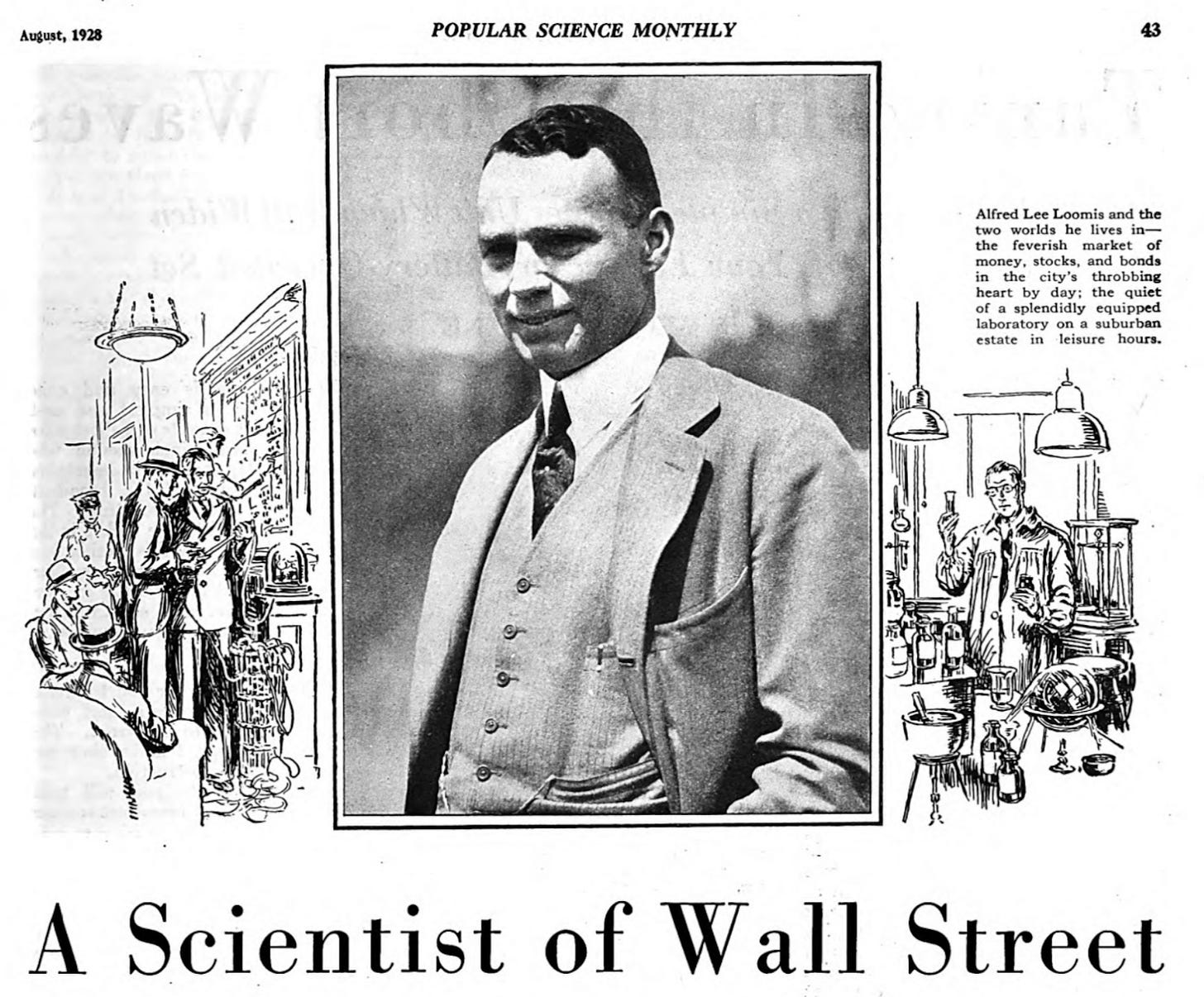

In 1928, The Popular Science Monthly ran a small feature on Alfred Lee Loomis, then an up-and-coming Wall Street trader.

“It is the peak of a rush day on the New York stock market. In the office of the vice president of a large Wall Street banking house, a dynamic, boyish-looking man sits at the throttle of a high-speed machine of finance...A few hours later, on a broad estate at Tuxedo Park, N. Y., miles from the city frenzy, this same high-powered business executive may be seen hard at play. In white apron, surrounded by curious test tubes, chemicals, and electrical apparatus, he is taking his recreation––in a physics research laboratory!”

–– Excerpt from “A Scientist of Wall Street” by George Lee Dowde Jr.

The word recreation here gives the impression that the laboratory was a calm oasis where Loomis de-stressed by fiddling with his scientific toys. Perhaps this is how he presented to the public, a rich, reclusive man who happened to have an unusual hobby. However, this “playtime research” also led to “some of the newest marvels of discovery in physics and biology.” This now seems like a more appropriate description of the operation that Loomis was running in his home laboratory––it truly was a “Tower of Science” and one that was frequented by the scientific elite, housing their most radical ideas.1

By building out his laboratory and working on cutting-edge research, while continuing to fraternize with financiers and lawyers as part of normal business operations, Loomis kept one foot in both worlds. He was constantly on the look-out for interesting scientific ideas and acutely aware of the demands of industry and government which helped him take on a pivotal role during WWII. In this new paradigm, he became another crucial cog tasked with keeping scientific progress at the forefront of the war effort. Here too, Loomis continued prioritizing the same principles that he used while working out of his Tuxedo Park lab: ensuring that critical projects didn’t face resource constraints, maintaining flat bureaucratic structures, and securing access to excellent talent.

Indeed, I argue that Loomis’s example shows that when a scientist is involved in allocating budgets and

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.