Day on Marx and Prayer

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.1

“Where, then, is the hope? Is the hope in hardship’s rushing gales? Ah, no, no more than God’s voice was in the rushing gales but was in the gentle breeze... But what, then, does hardship want? It wants to have this whisper brought forth in the innermost being. But then does not hardship work against itself, must not its storm simply drown out this voice? No, hardship can drown out every earthly voice; it is supposed to do just that, but it cannot drown out this voice of eternity deep within. Or the reverse.”2

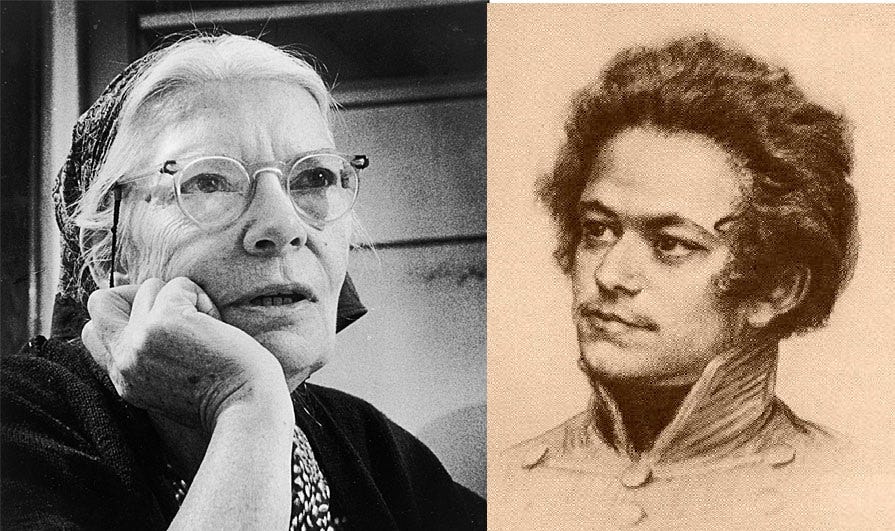

In 1927, a young woman embarked on her journey to take up the Catholic faith. In some ways, this is rather unremarkable: people join the church—Catholic or otherwise—every day for a variety of reasons with a variety of expectations and a variety of goals (or, even, a total lack thereof). However, alongside the remarkable miracle of an individual turned towards God, there was another, lesser remarkable event: a sinner, in her sin, had recognised her need for God in a turn brought about by the responsibility of a child, a life that reaches out in the need for a companion and a sojourner. This life was marked by sin—most notably, her profession as a journalist—and by saintliness, by love and by struggle; by very much only those things which are possible for a self. And, of course, it is only a self which can doubt without merely becoming a caricature of a given actuality.

Of course, Dorothy Day herself was aware of the struggle that emerges for an intellectual and passionate individual emerging from the chaos in the shattered carcass of Christendom. In her readings of Marx, where she had broached the infamous passage regarding religion’s place as the “opiate of the people”, she made a brave movement that the faithful rarely do—she agreed with him. In the dark night of the prole, it is absolutely true that those who live and have lived and will continue to live underfoot do indeed grasp for religious mysticism in an effort to escape their condition, to escape the cruel

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.