Political Cynicism and Public Reason

The summer break is over. The newsletter resumes to its regular activity!

Very short summary: This essay examines a paradox at the heart of liberal democracy: while we design political institutions assuming the worst about human nature, this very cynicism threatens to undermine democratic self-governance. Drawing on public choice theory and public reason liberalism, I explore how we might resolve this tension—and whether it's possible in an age of rising populism.

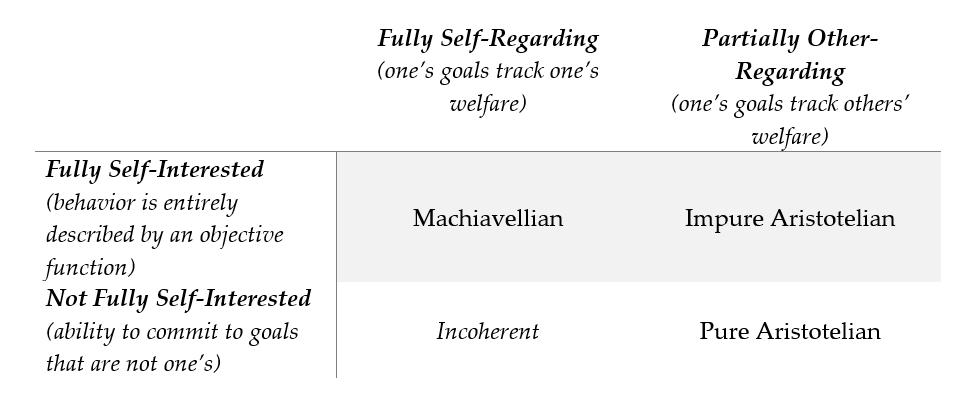

Social scientists, especially economists, are torn between two general behavioral models. Following the economist Samuel Bowles's terminology, let's call these models the "Machiavellian" and the "Aristotelian," respectively. On the Machiavellian model, individuals are self-interested and self-regarding. Self-interested individuals exclusively pursue their own ideals, values, and goals. The self-interested individual is the archetypal utility maximizer of economic theory, their behavior described by an objective function that reflects preferences over outcomes. However, a self-interested individual is not necessarily self-regarding. They can be altruistic if their utility depends on others' fate, or they can attach importance to conforming to what they perceive as prevailing social norms. An individual will be fully self-regarding if they care only about what happens to them, as in the standard economic model of the consumer. Let's call an individual who is self-interested and entirely self-regarding "Machiavellian."

It is easy to imagine a self-interested but partially other-regarding individual. Such an individual cares about what happens to others and values following social norms, even at personal cost. In some cases, they may even be willing to expend resources to punish norm violators without receiving any personal benefit in return. Of course, no individual can be exclusively other-regarding. In the economic language of utility functions, the choices of these individuals reveal a marginal rate of substitution between self- and other-regarding objectives. I call these individuals "impure Aristotelians." What would be a "pure Aristotelian," then? That would be someone who is not (fully) self-interested in the sense that their behavior is not entirely described by an objective function reflecting their goals, whatever they are. These are individuals who possess an ability to commit to goals that are not their own, for instance, the goals of a collective (a political party, a team) that do not directly align with their own preferences. Let's put aside for the moment the question of whether such individuals really exist and just accept this typology, as summarized in the table below:

These models are ideal types.

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.