Yale University Destroyed the First HBCU Before It Could Even Be Built

Deep Dives

Explore related topics with these Wikipedia articles, rewritten for enjoyable reading:

-

Dred Scott v. Sandford

1 min read

The article directly connects the 1831 New Haven vote to this landmark 1857 Supreme Court decision, showing how Judge Daggett's reasoning was cited by Chief Justice Taney. Understanding the full scope of this case illuminates how local anti-Black actions became constitutional precedent.

-

Nat Turner's Rebellion

14 min read

The article identifies Turner's August 1831 rebellion as the catalyst that transformed white New Haven's response from indifference to violent opposition. The full history of this uprising and its nationwide psychological impact on white Americans explains the timing and intensity of the backlash.

-

Prudence Crandall

16 min read

The article mentions Crandall as the target of Connecticut's 1833 Black Law, but her full story—opening a school for Black women, facing mob violence, and being prosecuted—represents another parallel attempt at Black education that was crushed in the same era and region.

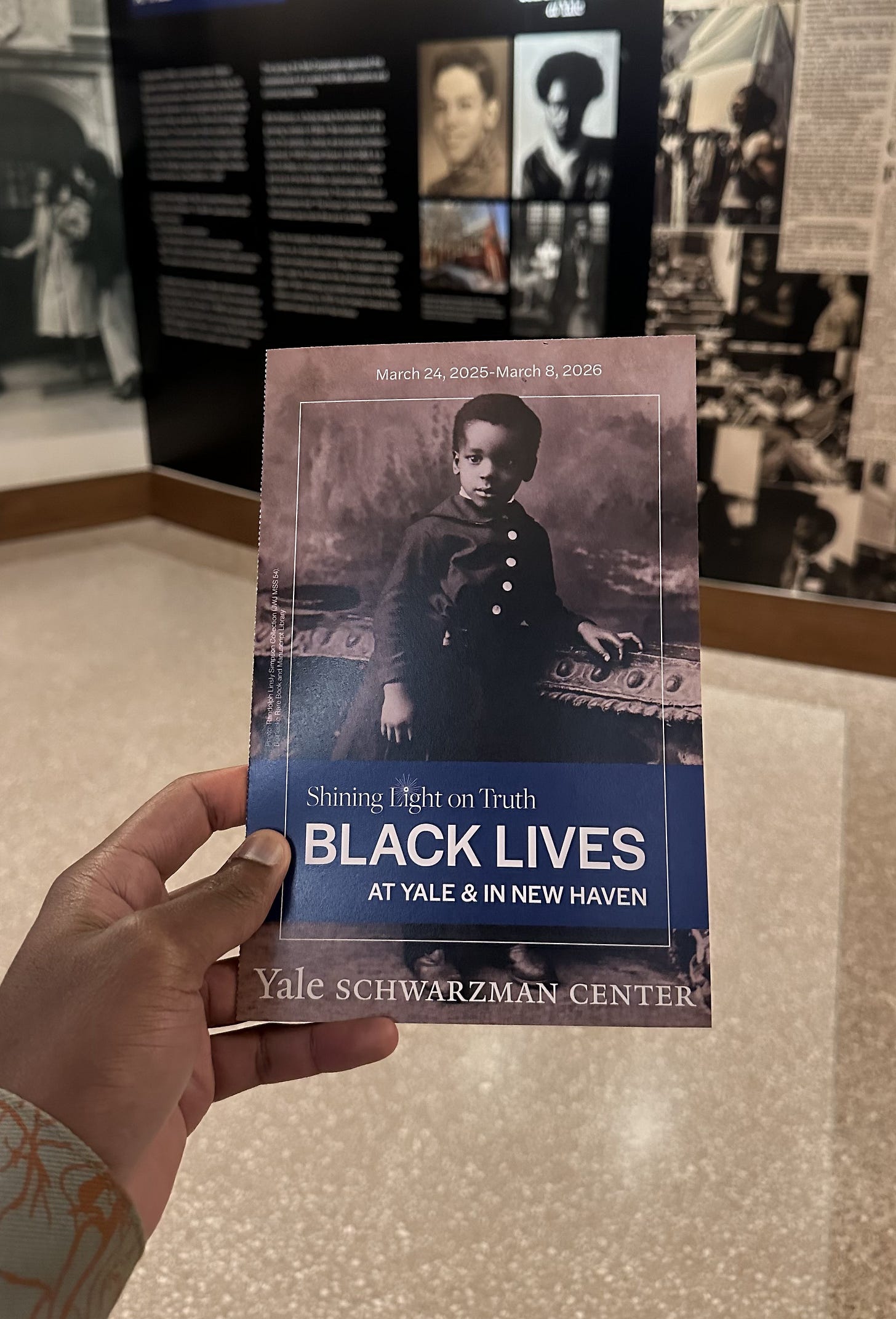

Earlier this year, I visited Yale for the African American Cultural Center’s 55th anniversary. While I was there, I wandered into an exhibition at the Schwarzman Center called “Shining Light on Truth: Black Lives at Yale & in New Haven.” It promised to illuminate “ongoing research that recovers the essential role of Black people throughout Yale and New Haven history.”

What I found was a story I had never heard. Not in any history class. Not in any documentary. Not once in my years of attending the school or as student body president.

In 1831, a coalition of Black leaders and white abolitionists came within inches of building the nation’s first college for Black men. They chose New Haven, Connecticut, raised the money, and purchased the land. And then 700 white men, many of them Yale alumni, gathered in a sweltering hall and voted the dream into oblivion.

That decision helped shape the legal architecture of American white supremacy for the next two centuries.

I’m working to document stories like the 1831 Black college proposal before they’re erased from public memory or dismissed as fringe history.

This work has no corporate backing and no wealthy sponsors. It depends entirely on readers like you.

If everyone reading this became a paid subscriber, I could investigate these buried chapters full-time, but right now less than 4% of my followers are paid subscribers.

If you believe in journalism that refuses to let power rewrite the past, please consider a paid subscription today.

“Friendly, Pious, Generous, and Humane”

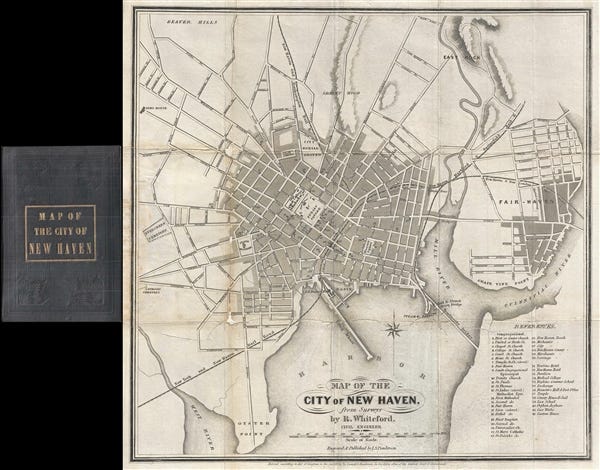

The plan was audacious. In June 1831, Black leaders from across the Northeast gathered at the First Annual Convention of the People of Color in Philadelphia. Delegates from fourteen cities, including New Haven’s own Bias Stanley and John Creed, endorsed a proposal to build a college that would offer Black men access to classical education, the mechanic arts, agriculture, and “all those things which make men happy.”

The site? New Haven, Connecticut. The reasons, as recorded in the convention’s official proceedings, read almost like satire today. Delegates praised the city’s “healthy and beautiful” setting, its “friendly, pious, generous and humane” inhabitants, and its laws that “protect all without regard to complexion.”

They had already secured $1,000 from New York philanthropist Arthur Tappan and identified a building: the former Steamboat Hotel on Water Street. Their

...This excerpt is provided for preview purposes. Full article content is available on the original publication.